Hearts, Minds, Wallets: The Simple Structure for a Successful Startup Pitch

Pitching = Storytelling. No matter what kind of pitch you're doing (on-stage, in a boardroom, etc.) you need to be a great storyteller. (#10)

The 100+ Sustainability Accelerator is a pilot program accelerator started by AB InBev, and currently in its fourth cohort. The Coca-Cola Company, Colgate-Palmolive and Unilever all joined the program as well. (Highline Beta, my company, was involved in the design, development & launch of the program.) The current cohort has 46 startups, and I’m lucky enough to be involved with all of them, specifically to support their pitch preparation for Demo Day.

Founders are pitching all the time—whether they’re raising money, selling, exploring partnerships, generating media attention or something else. There are pitches on stage (like a Demo Day) or pitches in a board room. There are 30-second elevator pitches, 60-minute deep dives and everything in-between.

Pitching matters.

Unfortunately, a lot of founders are still not very good at it.

The top 5 reasons why founders still struggle at pitching

Founders have a tendency to over-complicate. Founders have the “curse of knowledge” which means they’re (typically) experts in their field. This leads to the use of industry-specific terms or acronyms that others don’t always understand. It also leads to overly-detailed technical explanations of solutions. Things that may be obvious to a founder (i.e. a value proposition) aren’t necessarily obvious to investors or the people listening to your pitch. But instead of focusing on a value proposition, founders go into insane technical details that aren’t helpful. Many of the 46 startups in the 100+ Accelerator are working on extremely complex technical problems and solutions, and almost all of them will say, “I simply can’t explain this any more easily.” Wrong. You can.

Founders try to “stuff trends” into their pitches. Generative AI is all the rage right now, and investors are already seeing more pitches with references to it. Stuffing trends into a pitch ends up creating an alphabet soup of buzzwords, and (at least for me) diminishes my belief in a founder.

Founders try to fill gaps in their pitches with nonsense. Generally, founders know what investors want to see in a pitch (more on this later), but unfortunately this leads to a fair bit of make-believe, bordering on nonsense. Particularly at an early stage, founders will have plenty of gaps in their pitch and questions they can’t answer. IMO that’s OK, and expected. It won’t stop investors or others from asking hard questions, but fabricating answers or bumbling through superficial content isn’t going to do founders any favours.

Founders aren’t all great public speakers. For Demo Day-style pitches (think: TED talk style pitches) getting on stage is nerve-wracking. I totally get it. I get butterflies every time I get on a stage to present. I love doing it, but it doesn’t make me any less nervous. Doing pitches via Zoom might reduce the nerves, but it doesn’t reduce the need for being a great and engaging speaker.

Founders aren’t all great storytellers. Honestly, this is the crux of it. Pitching—particularly on stage—is about storytelling. People love and remember stories. Founders aren’t necessarily natural storytellers. And storytelling is hard.

Neil Gaiman is an amazing storyteller. If you’re not familiar with his work, check out The Sandman, American Gods and Neverwhere. Gaiman has a Masterclass where he defines the 6 elements of a good story, all of which apply to pitching a startup.

6 Elements of a Good Story According to Neil Gaiman

A natural arc from the beginning to the end of the story: From inciting action and rising action to climax and denouement, a good plot has defined story structure and maintains steady momentum.

A clear narrative voice: Whether you write in first person or third person, a story’s overall tone has a lot to do with the voice of its narrator.

A sense of genre: You could be writing a thriller, a satire, a romance, or a sci-fi epic, but they’re all united by clear genre elements. Choosing a genre can also help make a book marketable to audiences who may not know you, and this can really help if you end up pursuing self-publishing.

Compelling characters: Strong characters keep your audience invested. Imbue your main character with an internal conflict that drives their external struggle.

A structured storyline: Keeping your narrative organized and logically flowing will help you hold onto readers through all parts of your story. In this sense, fiction writing can borrow elements of journalism.

An insightful theme: Consider what ideas you want your reader to keep thinking about long after they’ve forgotten the specific plot of your book.

The two most important points are #1 and #5. Too few pitches have any real flow to them, they’re choppy and disconnected. Each point doesn’t logically move to the next; each slide is its own little island.

Good stories have flow and structure. So should startup pitches.

Hearts, Minds, Wallets: How to structure your pitch successfully

Some of you might read “hearts, minds, wallets” and think, “Wait, is this like that Adam Sandler song, ‘Phone Wallet Keys’?” Unfortunately, no. I’m not going to sing or rap anything. But if you’re interested in a good laugh:

Hearts, Minds, Wallets is the best structure I’ve found for structuring a pitch. It’s not an overly complicated framework, leaves plenty of room for creativity & interpretation, but improves the odds that you tell a compelling story. (Thank you Austin Hill; I believe you were the first one to say ‘hearts, minds, wallets’ to me.)

Let’s break this down:

❤️️ Hearts ❤️️

First, you need to connect with people emotionally. If you don’t, they’ll check out. This is especially true when doing a pitch on-stage. People will turn to their phones very quickly.

To connect emotionally, you have to understand your audience. Not everyone is solving a world-saving problem or curing cancer, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get people engaged, leaning in and thinking to themselves, “OK, this is something that matters. I should pay attention.”

Context matters. This can be a good thing if you have a pitch with a relevant context to the audience. But it’s also where there’s a huge disconnect. If you’re pitching what you might imagine as the “classic investor” (read: old white guys) about something that they have no understanding about, it’s a lot tougher. Their lack of experience with whatever problem you’re describing, means they don’t have context, and subsequently care less. Not always, but it happens.

Ultimately, if you can’t connect with people about something they care about, your pitch won’t succeed.

Quick side story (in the category of “I feel your pain as founders pitching”): In 2007 I was raising capital for Standout Jobs (which I’ve talked about extensively here and here.) I was new to fundraising, but having a few decent meetings. On a trip to Boston I met a fairly famous VC (name not included) and was pretty nervous. I don’t know if it was my pitch, the lack of interest in the topic, or something else, but the VC actually nodded off. He didn’t completely fall asleep, it was one of those head bobbing things, where he kept passing out, and catching himself. Ouch. I did not get a term sheet from that VC firm. 🤣

🧠 Minds 🧠

Once you’ve got someone engaged emotionally, you have to get them intellectually. This is what I would describe as the “meat and potatoes” of the pitch. The investor / audience is now saying, “OK, I get the problem, and I feel it. Now convince me you’re the one to solve it.”

This is the section where you have to demonstrate real credibility. You have the right solution, in the right market, with the right business model. You understand the competition and how you differentiate (in a meaningful way), have initial traction, and a great product roadmap.

💰 Wallets 💰

Finally, the ask. Once you’ve got me emotionally and mentally, you make your ask. When pitching on stage, depending on the context, you may not ask for a specific number, instead going with, “We’re currently raising a round” or “We’re aiming to start fundraising soon…” If you’re in a boardroom pitch with investors, have an ask. You might have a range (i.e. “We’re raising between $500k and $1M”) but you need a good reason for that, with differing plans/scenarios depending on what you raise.

Putting the pieces of the deck together

Many of you are likely familiar with the Sequoia pitch deck template (from 2015). A lot of pitches look that way, which is totally fine. There are variations as well and tons of recommendations online.

In my experience it’s less about the precise order of the slides and more about how the story flows. This is especially true if you’re on stage doing a presentation, whereas in a boardroom pitch to investors (or anyone) there’s a tendency to jump around when people ask questions.

Here’s a general structure that I think works (from a slide I’ve often used in presenting these concepts):

Should you follow this order exactly? No, you don’t need to. But generally, this works. You could easily put the product before traction. You could bring up the market size & opportunity and get to that first. You could skip competition. Part of this depends on the stage you’re at, how much detail you have (what you know and have confidence in, versus things you don’t know yet), and where you want to focus the story.

Here are a few good resources on deck structures, with examples:

How to Build Your Seed Round Pitch Deck by Aaron Harris, Y Combinator

How to Structure a Pre-Seed Pitch Deck by Russ Heddleston, DocSend

The Ultimate Startup Pitch Structure by Maurizio La Cava

50 Best Pitch Deck Examples from YC & 500 Startups by Team Superside

Pitch Deck Collection by Alexander Jarvis

Use cases. Use cases. Use cases.

One of the gaps I often see when founders are pitching is the lack of a practical (and simple!) use case that helps me (or the audience) understand the solution clearly (which helps clarify the problem, and the potential for problem-solution fit.)

Recently I was in a meeting and asked the founder three times, in different ways, “OK, interesting. But what problem are you solving?”

I couldn’t get a straight answer. It was confusing.

The founder was baffling me with terminology I didn’t understand. This is pretty common. I know I’m not the smartest person in the room, but ouch…

Founders occasionally try and “keyword stuff” their pitches (this isn’t an SEO game you’re playing!) You—founder—are probably the smartest person in the room, but that doesn’t mean your pitch has to prove that irrevocably.

Use cases are the key.

Walk me through the customer journey. It’s amazing how people can’t do this properly. It’s usually a sign that you don’t understand the customer/user well enough.

Tell me who the user is and why they care. In simple language. How are they going to actually use your product? If I understand that, I might get to the WHY (which is really what I’m after.)

Explain to me in X easy steps how the solution works (X < 10, please.) You can minimize the complexity because I don’t need all the details right away and your mumbo jumbo isn’t convincing. (I know you’re working on some generative AI, web3, 4-sided marketplace, with NLP, blockchain and quantum computing, but maybe don’t throw all of that in on the first pitch.)

“Building a community” is not a use case. It could be very important, but it gets tossed into a lot of pitches. Same with “platform.” Everyone wants to build a platform—I don’t even know what that means any more.

Use cases are practical. They help someone understand the key components of your startup: WHO is the user, WHAT they need, and WHY they care.

It’s easier to ask questions about use cases, and the questions reveal a lot. As a product person, I like to dig into the nuts and bolts of a product/solution. It helps me better understand the value proposition, and how you think about building—especially if you’re very early stage and haven’t built your MVP yet. Having a conversation on the “right size of an MVP” is super interesting and revealing. Talking about use cases unlocks the underlying assumptions you have, which are also interesting and conversation-worthy.

Please: When pitching, focus on use cases.

OK, let’s go through a few tips on how to pitch on stage and in-person:

Tips for on-stage “Demo Day” style pitching

Know your audience: This is always important, no matter what form of pitch you’re doing. But when you’re doing something on stage, try and get a sense of the breakdown of the crowd. For the 100+ Sustainability Accelerator, the demo day has a mix of investors, corporates (potential customers/partners), NGOs, government officials and other startup founders, all of whom care deeply about sustainability. In some cases the audience may be less diverse (i.e. all investors, or all potential customers, etc.) The make-up of the audience will impact what you present and how you structure your story.

The clock matters: Stage presentations are usually a specific length of time; Demo Day pitches are typically 3-6 minutes. Other types of presentations are also timed, in the sense that a meeting may be 30 minutes or 60 minutes long and you don’t want to consume all of that time pitching, but on stage, the clock really matters. Everything is choreographed, because you’re putting on a show.

Go with less detail: In a short period of time, on stage, with a mixed audience, you don’t really want to go into a ton of detail. You may not be able to explain all the technical complexities of your solution. You don’t want to show your financials. On stage, you go heavy on emotion, and stay out of the weeds.

One point per slide: This is one of the toughest things for people to do. They stuff slides with so much content it becomes impossible to understand what’s going on. When you’re on stage, and rambling on one slide too long, people lose interest. Shit gets confusing. The people in the back can’t read the font size (because you’ve put too many words on the slides.) Make one key point per slide, and if need be, have more slides. On stage that’s totally fine.

People won’t remember everything: Even in a full blown investor meeting, investors won’t remember everything, but they’ll be afforded the opportunity to dig in and ask questions. That’s not always the case with a stage presentation. In this case assume people remember 3 things at most. What do you want those 3 things to be? And if you’re participating in a Demo Day or an event where multiple startups are pitching, how do you stand out from everyone else? One suggestion: End strong on vision. Too many pitches end with the ask and use of funds. Yawn. Go back to the beginning of the pitch when you introduced the company, connected with people emotionally, and sell the dream. There’s a higher likelihood that people remember that than any other details.

Soundbites matter: When presenting to an audience, one of your goals is to give people a few soundbites that stick. That way those people, when networking at the event or elsewhere, can drop a couple easy tidbits of information. “I love Startup X’s mission to…” You can try shocking people a bit or giving them a fact they might not have realized. That way they can go to others and say, “Did you know …?” (People love sounding smart!)

Here are two great Demo Day style presentations.

The first is from Y Combinator, and the founder only has 2.5 minutes. They’re explaining a B2B and B2C business. Traction is a big part of this (because Y Combinator emphasizes growth during the program.) I always use this example when a founder tells me, “I can’t possibly explain my business in 5 minutes!” This founder does it in half that time.

The second one is from the 100+ Accelerator’s 3rd cohort. Plastics for Change is an awesome startup and co-founder Shifrah Jacobs does a great job.

Both of these presentations follow the hearts, minds, wallets pattern. They do it differently, but effectively.

Want to see more pitches? Check these out (Figma, Doordash, Coinbase, Replit, etc.):

Tips for in-person investor pitching

Be prepared to jump around: Some investors will let you go through the whole pitch and then ask questions, but I would aim for a conversation. The worst thing you can do when an investor asks a question (especially about something you haven’t spoken about yet) is to say, “Great question. I’m going to cover that shortly, let me just get through the rest of this first.” And, you’re dead. 💀

It’s OK if you don’t have every answer: This is especially true in the earlier stages, when your startup is new. Even after you achieve product-market fit you won’t have all the answers. Don’t pretend you do. Try answering a question with a question and ask for advice (investors love providing advice.) Founders that act as “know it alls” usually end up rambling too long and sucking up all the oxygen. The best investors aren’t trying to “catch you” they’re testing how you think. They’re trying to understand the underlying assumptions behind what you’re presenting. “Why are you charging $X?” “Why do you think your early adopters are Y?” Etc. Some might ask these things in an accusatorial, “looking down their nose” kind of way (because some investors are assholes), but try not to take it that way. Every question is a clue as to what investors care about, and there’s a good chance you’ll get the same questions over and over.

Pitching is hard. Rejection is harder.

No matter how good you get at pitching, you’re going to get rejected. Hopefully no one throws things at you on stage, or falls asleep while in a boardroom, but you have to expect a lot of “no’s.”

The founders of Airbnb had investors walk out in the middle of meetings:

“Some investors that Blecharczyk and his partners Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia approached in their early days walked out halfway through the meeting.” - https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/234709

Investors aren’t always great at giving you a definitive “no.” Often you’ll see them couch a “no” in some other way, potentially giving founders hope, and also leaving the door open just in case something happens (i.e. your deal becomes 🔥) Here are some “classic” VC phrases that are actually NOs (but maybe):

“Very interesting, keep me updated.” (by all means do, but they’re not investing soon.)

“Not right now, but maybe later.” (that’s mostly NO.)

“…” (this is silence / lack of response; sure VCs are busy—but this is a no.)

“Let’s keep talking.” (if from an analyst, that’s probably a no)

“Evaluating our portfolio mix at the moment.”

“We’re not sure about the [insert high-level reason here].”

To investors’ credit they don’t necessarily want to say something like:

“I simply don’t believe you have what it takes to win.”

“I’ve seen this idea 1000x times, and I don’t see what’s different here.”

So they try and provide more nebulous reasons for passing. This makes the overall process frustrating. My best advice is to listen to the questions they ask, because that’ll signal what matters (whether they say yes or no) and can help you improve your pitch (and your startup) over time.

The ultimate resource on pitching your startup

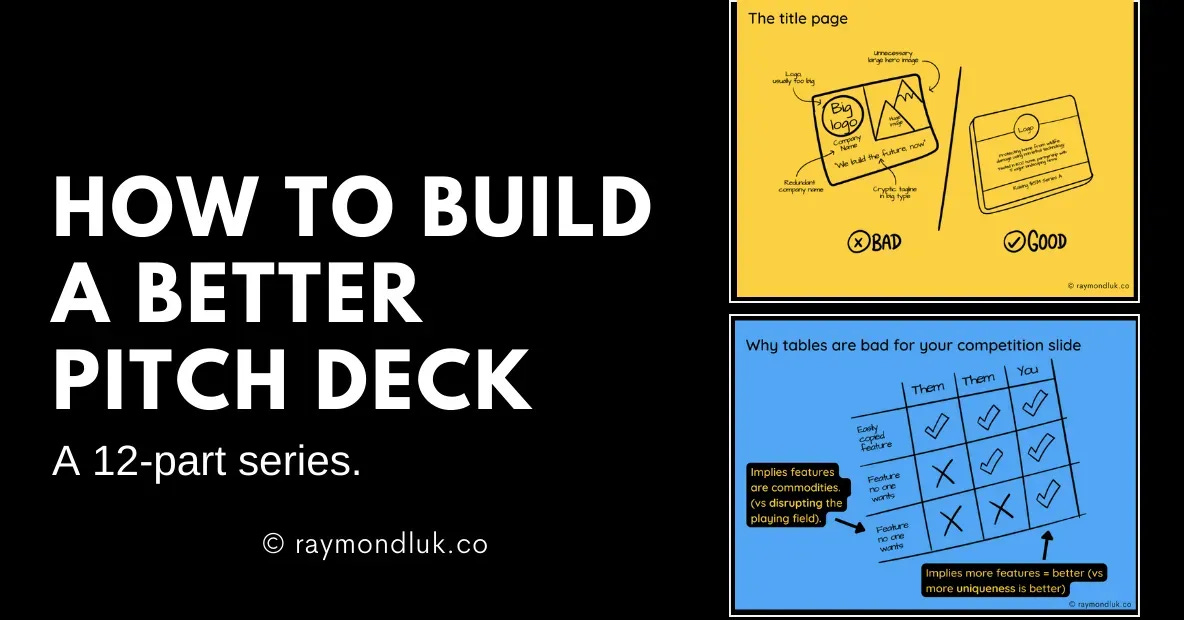

My good friend and co-founder of Year One Labs, Raymond Luk, has dedicated himself to helping startups improve their pitches. He’s going into every part of the pitch in a ton of fantastic detail—if you read his material, and use the advice he provides, I have no doubt your pitch will get better.

He’s doing all of this at Leap of Faith: The art of founder storytelling.

If you sign up for his newsletter, you’ll receive his free e-book. He’s also got Pitch Lab masterclass sessions (remote and in-person) and a bunch of other things going on. All about founder storytelling.

There’s so much to learn about pitching — from how to design a great deck (design matters!), to storytelling, to what details to include in each section of your pitch. In the end, it’s all important, but at the simplest level, try and remember: ❤️️ 🧠 💰.

Damnit Ben. You're putting too much value in the content you create. Now I am going to have to work extra hard just to be able to share insights that are maybe 5% as good if I'm lucky. :)