How to Define the Right Vertical for your Venture Studio

What is the right vertical to focus on when launching a venture studio? (#62)

After writing “The Future of Venture Studios is Vertical” I got two important questions:

Q: How do you define a vertical? And how do you know if a vertical is too small?

Let’s tackle these one at a time.

1. Defining a Vertical

Verticals need to be specific enough such that your venture studio has a clear competitive advantage and leverage when repeatedly building startups. If the second startup you build doesn’t benefit from the first one you built, you’re not getting enough leverage. Things should get easier as you build more startups. For example:

It gets easier to identify problems, because you spend a lot of time with a specific group of users/customers learning from them

It gets easier to acquire customers, because you know a lot of them and how to reach them

It gets easier to raise capital, because you have a targeted network of investors that care about your vertical

Etc.

Building a successful startup is about wrangling a ton of variables together into something meaningful. It’s about making endless decisions based on the incomplete information and your instincts. Building a startup is risky because there are a ton of unknowns.

What if that didn’t have to be the case?

What if many of the variables were already defined?

What if the decisions you had to make were reduced?

What if many of the unknowns were knowns?

That’s precisely the point of going after a vertical. You define and de-risk the variables, reducing the number of decisions and unknowns, in turn increasing the odds of success.

A vertical venture studio takes all the messy ingredients required to make a startup and puts them into a clearer recipe. You can’t completely eliminate the mess—there’s no perfect formula for startup success—but you can make the startup creation process easier, especially by rinsing and repeating within the same narrow vertical.

How do you define the right vertical to create meaningful advantage in building startups?

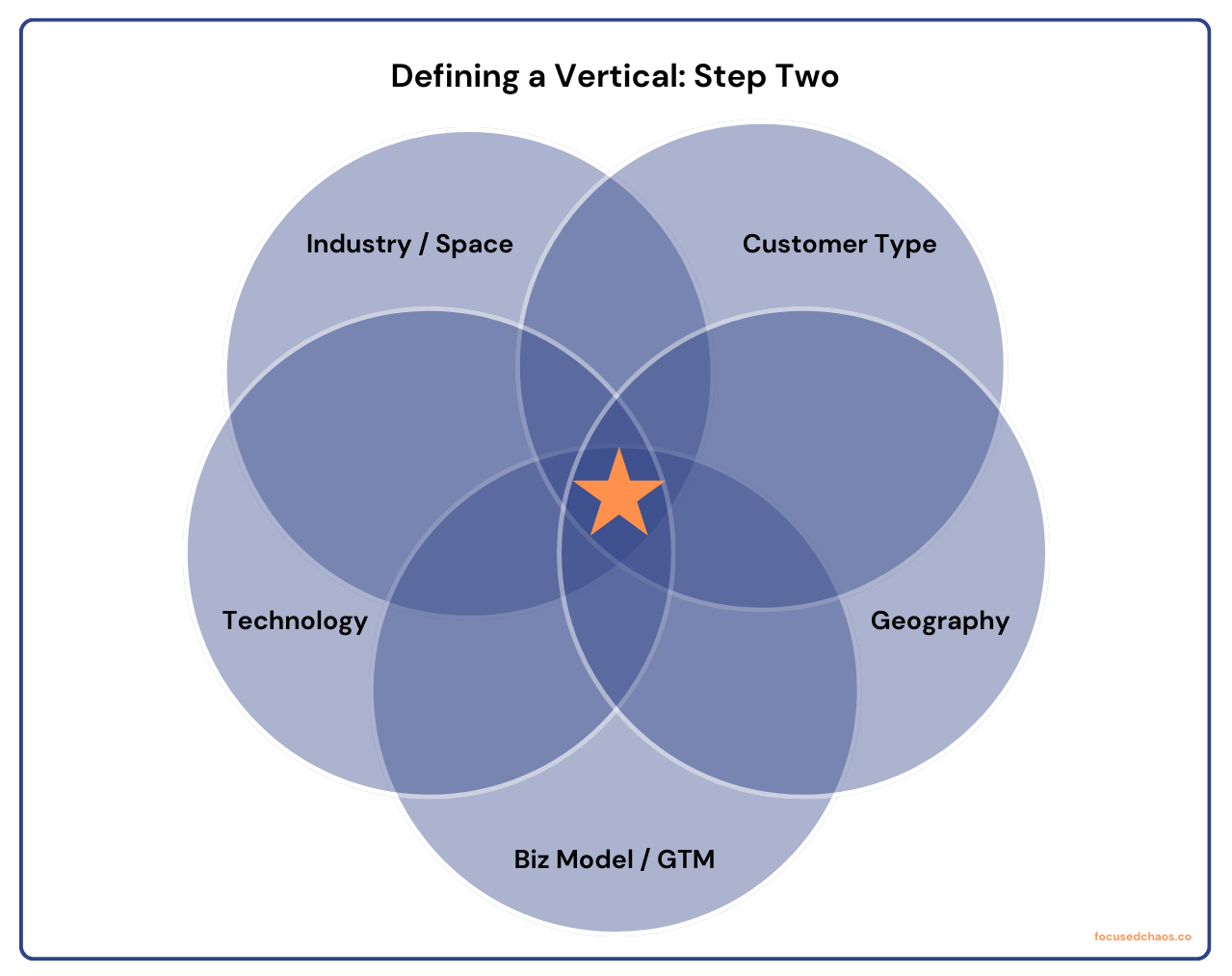

There are three key variables to help define a vertical:

The Industry / Space

Customer Type

Biz Model / Go-to-Market

First let’s look at Industry/Space

Often people start with a very big space such as FemTech, Financial Services/Fintech, Insurance/Insurtech or Sustainability. But these are too massive to provide any real leverage as you build startup after startup.

For example, the insurance industry has a number of different markets or verticals that are massive on their own. CB Insights puts together great market maps to illustrate this:

Insurance automation & digital transformation is a humongous area to focus on. Inside of this you have different customer types, business models and go-to-market strategies. You could attempt to build a vertical venture studio for “Insurance Automation and Digital Transformation” but it’s too broad.

Here’s another example from CB Insights:

This is simply too broad and complex to build a single vertical venture studio. You’ve got a wide range of tech (hardware and software) and go-to-market strategies / ICPs (ideal client profiles), including direct-to-consumer opportunities & enterprise carrier ones, etc.

Both of these market maps illustrate good starting points for a vertical—a sub-section of a broader market. Starting with insurance alone is pointless.

Next let’s look at Customer Type & Business Model / GTM

In insurance you could sell to a myriad of customers, including:

Consumers

Brokers / Agents (from SMBs to giant brokers)

Insurance carriers (from small to giant ones)

Reinsurance companies

Managing General Agents (MGAs)

Third-Party Administrators (TPAs)

Insurtech Companies (companies selling technology into the insurance industry)

To build a successful vertical venture studio pick 1 or 2 of these. You want to go very deep with any specific customer group to understand:

Their pain points (by doing constant customer discovery)

How they buy

How they budget

Competitors

Other technology they’re using

Etc.

Selling to carriers and brokers is different.

Selling to consumers and reinsurance companies is different.

Different is bad (in this context). You’re trying to remove variables and unknowns by picking a lane and sticking with it.

Once you’ve defined a customer type, the business model(s) and go-to-market strategy become clear. You don’t sell expensive annual contracts for an enterprise SaaS product to consumers. Similarly the go-to-market for acquiring consumers on a new insurance product is radically different from the enterprise salespeople you’ll need to sell to global insurance carriers.

The biggest risk for most startups isn’t technology; whatever you want to build is typically doable. The biggest risks are twofold:

Will anyone care?

Can you acquire customers and make money?

To mitigate the risks for these two, you pick a customer type + business model/go-to-market strategy and you rinse and repeat, over and over, until you become experts at selling to customer type A, B or C (but not all of them at the same time!)

Your studio team is dependent on your vertical

Venture studios need the right team to support founders in building their startups. That team should be specialized.

Think about things like go-to-market and monetization. There are very few growth marketing people that are experts at B2B and B2C, with expertise in every channel and business model.

You can find D2C growth experts that know how to build brands and market to consumers

You can find B2B growth experts that know how to sell enterprise software to big companies

You can find B2B growth experts that know how to use a freemium model to sell to small businesses

But I can almost guarantee these are three different people. If you want someone on your studio team that’s an expert in go-to-market and growth, you better be in a vertical.

What are some good examples of verticals?

Evaluating the three key variables, here are some vertical examples that make sense:

Cross-Border Payments (Fintech) + Big Banks + Enterprise SaaS/Sales

Cross-Border Payments (Fintech) + SMBs + Freemium

Water Infrastructure, Management & Efficiency (Sustainability) + Fortune 100 CPGs + Enterprise SaaS/Sales

Water Infrastructure, Management & Efficiency (Sustainability) + Municipalities + Enterprise SaaS/Sales

Fertility (FemTech) + Consumers + Subscriptions

Fertility (FemTech) + Hospitals/Clinics + Enterprise SaaS/Sales

By defining verticals this way, you’re making a few critical things easier and repeatable:

Problem validation: Perpetual customer discovery = ever-growing database of insights

Customers: Secure customer (design partner) relationships, making it easier to sell new solutions

Go-to-Market Playbooks: Identify the right channels & go-to-market strategies for your customer type

Business model: How you make money is likely consistent between startups, making it easier to execute & benchmark

The execution work of validating a problem, building a solution and bringing it to market successfully should be much easier if you’ve identified a narrow enough vertical to rinse and repeat through these key steps.

What other variables are there for defining a vertical?

There are two additional variables that are important: Technology & Geography.

With the explosion of AI, I’m seeing more venture studios use AI as a “horizontal vertical.”

AI is not a vertical.

It can literally be applied to any industry, and is useful for a bunch of problems. Having AI tech/capabilities is super valuable but it doesn’t address most of the key variables for building great startups. It may be a differentiator or competitive advantage, but only if you figure out where to point the technology.

Technology can provide leverage.

Does it really make sense to start every company in your studio from scratch? Or to try and build across a bunch of tech stacks?

Are you going to build software and hardware companies? I wouldn’t.

Technology is also heavily influenced by customer type. For example, if your studio only builds Enterprise SaaS startups, you better be ready for intense security vetting. If you’re building medical devices for consumers, you better know how to get FDA approval.

The technology focus also impacts who you hire on your tech team. There’s a difference between a full stack developer, data scientist, AI prompt engineer and hardware engineer.

Pick any of the verticals defined above, and add technology to the mix:

Cross-Border Payments (Fintech) + Big Banks + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + AI

Water Infrastructure, Management & Efficiency (Sustainability) + Fortune 100 CPGs + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + Hardware

Fertility (FemTech) + Consumers + Subscriptions + Physical Goods Manufacturing (which is similar to technology)

Finally, let’s look at geography.

Most startups start in a geography and then aim to expand. Others don’t intend to expand beyond a core geography because of the complexities in doing so, specifically around regulation & compliance.

Selling a consumer insurance product in the United States is different from doing so in Canada, Europe and everywhere else

Selling to big banks in Europe is different from how you sell to big banks in North America

Etc.

Regulatory, compliance and legal issues are a big deal in certain verticals. If you’re in a regulated industry it makes sense to narrow the geography. Become experts in the issues within a specific geography and focus there.

Let’s look at the examples again:

Cross-Border Payments (Fintech) + Big Banks + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + AI + North America

Water Infrastructure, Management & Efficiency (Sustainability) + Fortune 100 CPGs + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + Hardware + Europe (b/c they have more regulation happening)

Fertility (FemTech) + Consumers + Subscriptions + Physical Goods Manufacturing (which is similar to technology) + United States

Certain geographies will have a bigger appetite for solutions (perhaps because the problems are more acute, or their adoption of new technology is higher). For example, Web3 gaming is more popular in Asia (South Korea, Japan & China), and so it makes sense to build a vertical venture studio for Web3 gaming in that region.

When you combine all of these elements, you’ve significantly reduced the variables, which increases the odds of success.

Another way of looking at this is through the lens of Desirability - Viability - Feasibility (DVF). DVF is a framework for identifying and assessing uncertainty.

You need to solve all three to build a startup. Focusing on a vertical helps.

Desirability: With a narrow customer type (well-defined ICP) and easier access to those customers, you can determine desirability more quickly and regularly; uncovering new problems (that others may not even know exist). Being insanely close to customers also helps validate a willingness to pay, through a standard business model that you’re an expert in delivering.

Feasibility: You can use a “horizontal vertical” (such as AI) to give you a competitive advantage and deliver solutions customers really need. You can focus on a specific geography and become an expert in the relevant compliance/regulatory/legal issues. You should recruit the right tech + operations team to build similar solutions over and over.

Viability: You’re running a small number of go-to-market playbooks, with expertise on the specific channels that work for your customers and business model, so you can get to market faster and hit key traction milestones. Your access to customers increases confidence in your ability to sell (and know how much to sell for), even before you build anything.

Focusing on a narrow vertical will help you attract the right founders & investors

If your venture studio delivers on its promise of making it easier to build great startups in a specific vertical, you’re going to attract the best founders that want to build startups in that vertical.

You have the customers, specific playbooks (that actually work!), experience/expertise, tech stack and team to build great startups in a specialized space—why would founders interested in that space build on their own? They should get the value & leverage your studio provides.

Founder recruitment is possibly the most important aspect of any venture studio.

You’ll need founders approaching you inbound (which is easier if you’re known for something) and you’ll likely have to do outbound recruiting as well (it becomes easier to target the right people based on your vertical).

Finding the right investors (for your studio or your startups) is critical. Studios can’t fund everything on their own. There are definitely investors out there focused on broad verticals (i.e. Insurtech), but narrowing further is going to make the value proposition for investors even clearer. It becomes much easier to build a strong investor network / ecosystem when you’re focused. There will be fewer total investors in your network, but that won’t matter, because the investors you do build a relationship with will be the right fit.

2. Defining the Right Size Vertical

What if the vertical I pick for my venture studio is too small? That was the second question (which I’ve gotten several times). People are worried they could go too narrow.

I suppose it’s possible. Let’s look at another CB Insights market map:

Any one of these individual areas may be too narrow, because you’d end up building competitive businesses

But if you apply the key filters to this map—Customer Type, Biz Model/GTM, Technology & Geography—I think you’d have a number of very sizeable verticals worth pursuing

Another way of looking at it is based on the number of startups you want to build. Let’s say you’re aiming to build 5 startups/year. As long as you believe you can do so, without those startups (at least initially) being competitive, you’re in a big enough vertical.

Let’s go back to our examples and ask ourselves, “Can I envision 5 startups scaling in this vertical?”

Cross-Border Payments (Fintech) + Big Banks + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + AI + North America

Water Infrastructure, Management & Efficiency (Sustainability) + Fortune 100 CPGs + Enterprise SaaS/Sales + Hardware + Europe

Fertility (FemTech) + Consumers + Subscriptions + Physical Goods Manufacturing (which is similar to technology) + United States

I’d say the answer is “yes.”

Are there are 50 startups that could exist in each of these verticals? Probably, because these markets are still enormous and constantly changing. But that may be a stretch, in which case, you have to explore expanding the vertical or going into new, likely adjacent, verticals.

For example, you might start with Cross-Border Payments + Big Banks + Enterprise SaaS + North America and then expand to a different customer type or geography.

Honestly, I wouldn’t worry about whether or not the vertical is too small. I’d focus on picking a lane, being the best in that lane, and building great startups. If you can figure that out and start to repeat the success rate (which is damn hard, no matter what!), you’ve got something. And that something will attract more quality founders, investors, team members and ecosystem partners, while increasing your expertise with uncovering problems, building solutions, acquiring customers, and business building, driving a flywheel of startup creation within your vertical venture studio. That’s the kind of “hand” you’re looking for.