Shutting Down Your Startup

When is it time to shut down? How do you go about it? It's never easy. (#24)

Most startups fail. It’s a disappointing reality that founders and investors face all the time. When someone starts a company they don’t expect it to fail, but odds are that it will. Despite the frequency with which this happens, the actual decision making process to shut down and how to do it are not often talked about.

Sidebar: My postmortem of Standout Jobs

In 2010 I sold the assets of Standout Jobs, a startup I had co-founded in 2007. It was not a successful experience and I wrote a postmortem. More recently, I reflected on that postmortem and shared updated thoughts in two newsletter posts: 1 | 2.

In the second post, I included a list of other postmortems written by other founders. They’re all worth reading.

When I asked for some additional stories on Twitter from founders that have shut down their startups, Brett Martin wrote this:

Question: When should you shut down your startup?

“When you run out of money” is the simplest answer. It doesn’t make the process of shutting down any easier, but you’ve run out of options. You shouldn’t wait until the bank balance is actually $0 because it costs money to wrap everything up.

I did speak with a few people that got to $0 (or very close) and kept going, not paying themselves, reducing costs to an absolute minimum, in the hope that they could turn it around. In some cases they found a soft landing for the assets, recovering “cents on the dollar” but in other cases things languished.

The decision-making process that I recommend is as follows:

1. Do you still want to keep going?

This is an incredibly personal decision. It helps to have trusted mentors that you can speak to about the challenges you’re facing, because making this decision alone is tough. Ultimately, no matter how much help or support you have from employees, mentors, investors or family members—it’s going to be your decision. No one will or can make it for you.

Don’t keep going for other people.

You will feel a lot of guilt and responsibility to those around you:

If you raised capital, you’ll worry about what investors will think of you.

If you have employees you’ll worry about their livelihoods.

You’ll worry about your customers and how they’ll feel.

You may feel embarrassed amongst your peers, friends or family. You’ll worry about your financial responsibilities.

I can tell you from experience (and from others I’ve spoken with):

Investors understand the risks of investing. It’s why they take a portfolio approach. As long as you communicate actively with them, you should be fine. If they treat you poorly during the process of shutting down your company, don’t work with them again. Good investors will help you through this process. Crappy ones will abandon you (or worse: talk trash about you.)

Employees should understand the risk of working for a startup. Shit happens. They’ll be disappointed and scared (for themselves), but hopefully they understand. It’s definitely worse when it’s a later stage startup that’s raised a lot of capital and looks like a rocket ship. Anyone joining an early stage startup should know the risks. Your goal is to give employees as much time as you can to find alternatives, and help them with “soft landings” (i.e. find other work.) You can’t invest a ton of time doing this, but any little bit helps.

Investors care less about you failing than you think

Elizabeth Yin from Hustle Fund nails it from an investor perspective (you should read the full thread):

I’ve done this myself. Sure, I’m disappointed when a startup I’ve invested in fails, but I understand the risks, and the founder’s wellbeing is more important than trying to squeeze a return.

If things are going sideways, you need to communicate.

As soon as you stop communicating with investors they’re going to write you off. And worse, you’ll lose credibility and their trust. If you manage the investor relationship well, those investors may invest in you again—this is quite common, even if you fail. I’ve done this a couple times. But I’ve also had experiences with founders that didn’t communicate and then disappeared, treating me (and other investors) poorly—safe to say I won’t invest in them again (and if anyone asks me privately about them, the reference will not be positive.)

Investors are in a tricky spot when it comes to failing startups. On the one hand you might think they should double down to help “by any means necessary.” And often they do roll up their sleeves to try and stem disaster. But it doesn’t always make sense. The opportunity cost of doubling down on something that’s going to lose is high. Investors have a portfolio to worry about and if they focus too much energy on those that aren’t going to generate significant returns, they’re not doing what’s in the best interest of their funds. It’s why you may feel somewhat abandoned by your investors if things are going sideways—they have to “cut and run” to focus on the winners. This does not mean they should treat you poorly or ignore you, but you have to appreciate their goals as well.

OK, back to you.

You’re the founder. You have to decide if you still have the strength and will to keep going.

If you don’t, you should move on. The odds of you turning something around when your heart isn’t in it are very small. And the opportunity cost for you is huge.

It’s why I believe your purpose (i.e. why you started a company in the first place) is so important:

Let’s assume you do want to keep going. Now what?

2. Do you have a plan for what to do next?

If things aren’t working, doing the same thing over and over isn’t going to solve the problem. You can’t keep going, mindlessly pursuing the same strategy, hoping that something magical will happen and you’ll win. There’s perseverance and then there’s insanity. Perseverance is good (within reason); insanity is not.

When a startup wins, a decent portion of that victory is often attributed to luck. Most founders will agree with that. But waiting around for luck is a death trap. “You make your own luck” means you put yourself in a position to be lucky, for good things to happen—which is different than sitting in front of your computer willing the answer into existence.

If you have the strength and commitment to keep going you need a plan. You have to do something—and while you’ll get plenty of advice (solicited or otherwise), you have to decide what to do.

First, you need to reduce burn as much as possible.

You may have already started this process, but you should figure out how to be more aggressive. There’s no time to waste, and unfortunately there isn’t any time to be sentimental either. Cut everything you possibly can. Do what you can to give yourself maximum runway—to survive like a camel (or cockroach).

Next, you probably should explore a pivot.

It’s possible with a reduced burn that you can keep “doing what you’re doing” and survive long enough to come out the other side. But more likely, you know that your current approach isn’t going to work no matter how long you survive, so you’ll need to pivot.

A pivot is a change in strategy (ideally 1 thing changes at a time) based on learning.

For example:

You might realize you’ve targeted the wrong customer (ideal client profile/ICP) so you pivot to a new customer or market.

Or you might realize that you have the right customer, but the product is wrong. It might mean changing something significant in the product or going after a completely different problem with something new (but targeting the same customer.)

Or you might realize that you have the right customer and the right product, but the wrong business model.

These are changes (minor or significant) in what you’re doing based on something you’ve learned.

Startup success is based on learning and speed of execution

The likelihood of startup success is dependent on the rate of learning and execution. If the rate of learning is high, you still have a chance, especially if you can identify an opportunity to pivot (in a small or big way.) Your job is to run rapid experiments, inexpensively, learn quickly and make fast decisions—with the goal of generating sufficient traction or progress to justify continuing. If the rate of learning is low, you’re in trouble.

If you have to cut so deeply that you can’t execute quickly anymore (i.e. there’s no one around to do the work), then pivoting won’t work. You may buy yourself more runway, but the speed of execution will be too slow, which in turn kills the speed of learning. If you can’t execute, you can’t learn, if you can’t learn, you can’t win.

Pivots vs. Resets

If you’re making a change without any real learning then it’s not technically a pivot (although these are often described as pivots)—it’s actually a reset or do-over. A Hail Mary.

Hail Mary’s are last minute throws down the field that have a low chance of succeeding. But if they work, huzzah!

A Hail Mary is when a company abandons what they’re doing for something completely different, and there’s no correlation between the two. It’s a reset.

It’s usually not well planned out. It’s more a shot in the dark or last ditch effort that you hope will succeed. It might, but the odds aren’t great, especially if you’re running out of funds and time. And if your approach is to go in a completely different direction, and in effect start from scratch, you may find your investors, employees, etc. are less than eager to do so.

Pivot (and reset) examples

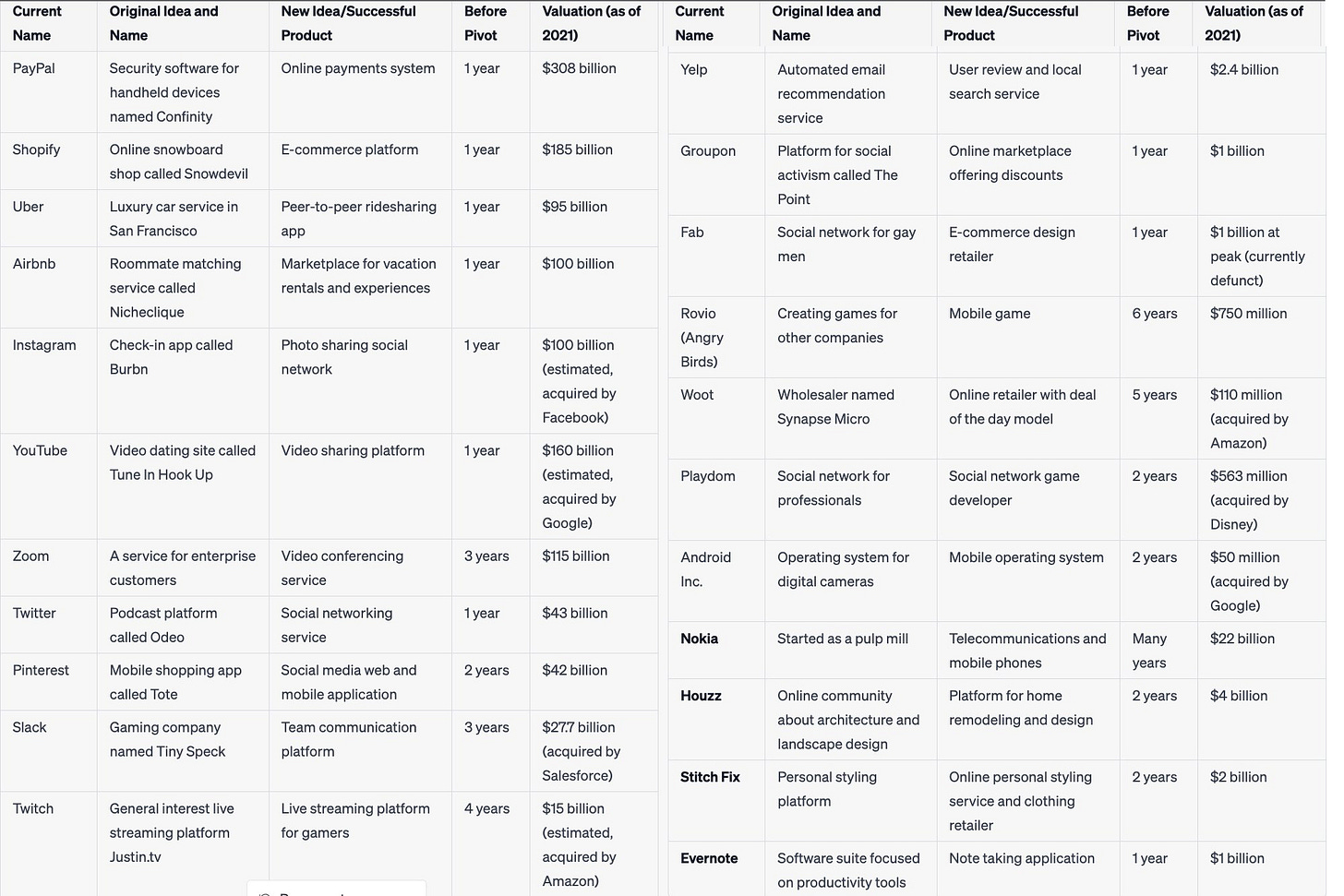

There are lots of examples of pivots (or Hail Mary resets) that became insanely successful. Micah Friedland asked ChatGPT for some insight and then shared the following:

You can debate if these are all pivots (some like Uber may have been the plan all along), or resets (i.e. Nokia started as a pulp mill in 1865!), but nevertheless what’s compelling is that a lot of successful businesses started as one thing and ended up somewhere different.

The decision making process is complicated but still starts with you

Deciding to shut down your startup is never as simple as I’ve described. The emotional turmoil and stress are incredibly high, and you can’t reduce the answer to a few simple questions. But, I’ve tried. 😄

Here’s a simple flowchart that may help you:

It’s also important to note that all the founders have to be on board with the plan. If they’re not, either the disapproving founder needs to be exited, or you have to shut the company down. When things are going sideways the founder relationship is stress tested to the extreme. Many founders do not survive, and ultimately break up.

If you shut down, the feelings of failure will hit you

Shutting a startup down is failure. We shouldn’t sugarcoat it, celebrate it or pretend it’s not real. It hurts. Worse, you will probably feel like a failure.

I can only hope that you recover quickly from those feelings, because out of failure comes the potential for incredible learning. You’ve probably heard the phrase, “We learn more from our failures than our successes.” I think that’s true (although I still prefer succeeding over failing!)

You can learn a ton from failure, which can lead you to winning the next time (or the next time; or the next time after that.)

Some people I spoke with jumped right into starting something new after winding down their startups. Others took a moment, reflected, recovered and then started anew. You do what you think is best for you, but I lean towards pausing and taking a step back to gain perspective. Rushing into things head first (which has historically been my approach!) doesn’t necessarily give you the time to really let things soak in (both the failures and the successes.)

Jason Lemkin shared this post with me, “Never Quit If.”

It’s a recognition that startups are incredibly difficult, but if you keep pushing forward you may succeed.

In the post he shares 5 targets that should lead you not to quit (specifically focused on SaaS businesses.)

Should you return capital to investors?

With all the chaos surrounding startups and fundraising, I started seeing more discussion about founders returning capital to investors. I wanted to get a sense of how people feel about this, so I asked:

This was far from a scientific poll, but investors were genuinely torn. Here are some of the quotes from the Twitter thread:

Pat Matthews, Founder & CEO at Active Capital said, “It’s often obvious when it’s time to return capital and move on and I’m all for it. Burning money for the sake of it is silly and most founders are talented people just working on the wrong thing.” I complete agree with this, although I think it takes a good relationship between the founder and investor to broach the conversation.

Rodrigo Mallo, GP at Outsized VC said, “I think my LPs don’t pay me to avoid mistakes but for how right I am when I’m right. So if the founder/s want to keep going, I’m usually ride or die.” The key here is the founder wants to keep going—many of the investors in the thread said the same thing, they’ll back the founder until the end, if the founder has conviction.

Alexander Kolpin, MD at Seed and Speed said, “I have had this in my portfolio. I respected the honesty + would invest in these founders again. However, if it is due to a lack of general conviction, resilience, etc. I would not invest again + tell them rather not to raise again. There are better uses of their time + our money/time.” I get Alexander’s point, but I think “lack of conviction” and “resilience” are different things. A lack of conviction may come from running out of reasonable experiments to run and a rate of learning that’s too slow. Maybe the market shifts and your plan is no longer valid, and you don’t have another plan you believe in. That happens. And that’s very different from giving up quickly because you don’t have the stomach for the ups and downs of startups.

Martin Tobias at Incisive.vc said, “If they don’t have a pivot, I suggest shut down. I will have more respect for that founder.”

Dylan Itzikowitz at Expa said, “I’ve spoken to too many (typically young) founders that would rather the extra months of paying themselves a salary to ‘be their own boss’ than give the money back and get a job.” This is pretty frightening, but not terribly surprising. When the hype machine is roaring a lot of people jump into starting companies. When things get tough, those people often bail. In this case I get the sense that a lot of people thought starting a company was cool and fun—and now they’re dragging it out despite not having any real traction.

Robert Lendvai, angel investor said, “I’ve had two of my startups return capital. Frankly, that impressed and surprised me. Contrast that to another founder who lied to me about his business, took my capital and then closed the doors shortly thereafter without even telling me.” This one hits home. I’ve had this experience, where a founder just disappeared. No updates, no news. It’s a terrible way to treat anyone, including investors.

So should you return capital to investors?

Here’s my suggestion:

If you’re leaning towards shutting down because you’ve lost belief in the plan and don’t have an alternative to pivot into, you should at least have a conversation with your investors about returning capital and moving on. It’s important to walk investors through your thinking and how you got to your conclusion. Hopefully it leads to a healthy dialogue. It may also lead to the exploration of an acquisition or asset sale. If you’re going to pursue those options, put a timeline on them, so you don’t burn right to zero.

You may have a Hail Mary type opportunity you want to pursue, which you should pitch to your investors first before jumping into. If they’re on board, go for it. If not, then explore shutting down and returning capital.

We’re going to see a lot of nonsense

Current market conditions are not good for venture-backed startups. A lot of startups raised big dollars during the peak of the hype cycle at astronomical valuations, and now they’re struggling. Bridge rounds are the most common form of funding. New investments have dropped considerably as VCs sit on the sidelines. It’s not a pretty picture.

Amidst all of this, I learned about several high profile startups (in Canada and the US) where the founders are holding money hostage in exchange for a payout before they return capital. In some cases, it’s the investors that are looking for the capital to be returned. They now realize they invested at untenable valuations into companies that won’t make it (or will take too long to figure things out). Their funds are maturing and they need to start raising for a new fund, but their portfolio is a dog’s breakfast. So they apply pressure to founders to return capital. Founders, who also see the writing on the wall, are asking for large payouts in order to shut their startups down faster and return as much capital as possible.

The unpleasant and unscrupulous behaviour is increasing on both sides of the table, from investors and founders. Everyone is looking to cash in on whatever they can and save (some) face, because of the downturn in the market.

Your reputation is made during tough times. If you look to screw people over when the shit hits the fan, people remember that. That’s true if you’re a founder or investor.

There’s no easy way to approach the question of shutting down your startup. So the only right way to do it is transparently and proactively. You may not get the response you want (i.e. some investors might abandon you, or pressure you to do things you don’t want), but you’ll know you did what was right. More often than not your investors will support you (and back you again), your employees will understand and appreciate the transparency and support, and your family, friends and community will be there to pick you up.