The DOs and DON'Ts of Startup Advisors

Startup advisors can be extremely valuable, but you need to find the right ones and engage them in the right way. (#19)

When it comes to running a startup, there are a number of topics that generate significant debate. Should you raise funding? How much? How much equity should you give early employees? How do you deal with co-founder conflict? How much validation should you do? When have you achieved product-market fit? And so on.

One of those topics is startup advisors.

If you ask Twitter (which I did) you get a lot of interesting answers.

On some topics, most people agree. On others, they’re quite divided. What a surprise! 😆

I’ve had advisors for my startups and I’ve also been an advisor. I’ve seen the good and bad.

“Startup advisor” is the wrong name

I don’t love semantic debates (they make my head spin), but in this case it’s important.

I believe, the best startup advisors should focus primarily on the wellbeing and success of the founder(s), irrespective of the startup. The best advisors are actually “Founder Advisors,” more aligned with how you might think of “mentors.”

A founder advisor is someone that does have specific expertise & experience that the founder(s) is leveraging, with specific deliverables & asks, but the advisor’s main job is more mentor-like to the founder—a trusted confidant, great listener and sometimes, a shoulder to cry on.

IMO, the best advisors are…

There to support you as a founder above everything else (and don’t disappear when things go south)

Compensated with equity

Given specific deliverables that they’ve agreed to (contractually), which helps define the level of commitment they’re providing

Always available

Possibly only working with a founder for a specific period of time throughout the lifespan of that founder’s startup

Bringing on Industry Experts as Advisors

In 2007 I started Standout Jobs, which was in the recruitment space. The company was not a success. To be clear this wasn’t the fault of my advisors!

If you want to learn more about my experience running Standout Jobs and the postmortem I wrote, check out these two posts: Part I and Part II. I cover a lot of topics including fundraising, timing, investor management, product & engineering, go-to-market strategy, pivoting, etc. I lived what felt like 10 years of startup experience compressed into ~3 years.

I wasn’t an expert in the recruitment space, and felt that it was important to bring on advisors with domain experience. They could guide me through various pitfalls and challenges in the market and lend credibility.

My advisors did both of these things, but there was a limit. They weren’t great at helping me acquire customers—my sense is they were too busy (rightfully so) selling their own products/services & building their own brands, and weren’t quite ready to use that level of social capital to refer me. I don’t recall getting a single customer from my advisors.

Lending credibility in a gigantic market to a “cool startup” is relatively easy. Having a few advisors that were well-known in the industry allowed me to “get in” and build a network. That was valuable, but the network I built was with others in the recruitment space (i.e. “insiders”), not necessarily customers. Reputation is important, but it takes a long time to build and then translate into meaningful value creation. Standout Jobs didn’t have that kind of time.

Recommendations on industry experts as advisors:

You can bring on advisors that lend industry credibility to what you’re doing, but get more out of them than that. With Standout Jobs, we collaborated on content with at least one of our advisors, which we could use for marketing purposes. That was helpful. The key is that they do more than simply lend their name to you.

“Celebrity or big name advisors” (those that are well recognized in an industry) might look cool on a pitch deck, but you’re probably not getting enough value from them; if you know them well, great, but if not, be careful.

Bringing on Functional Experts as Advisors

In the pitch decks I see, functional experts (i.e. marketing, product, hiring, etc.) are less commonly represented as advisors. But I think these advisors can be extremely valuable because of their deep practical experience.

The challenge is that these advisors may have a “shelf life” whereby you need them for a period of time and then no longer need them as much. I’ve had this experience with a few startups that have brought me on as an advisor in the earliest stages (often with a focus on building product.) As the company scales, my expertise became less useful (although in one case I started advising/mentoring the VP Product more than the CEO.) Moving on from an advisor may be awkward. But it’s more awkward to maintain a relationship with an advisor who isn’t really advising any more.

Startups can outgrow advisors. It’s going to happen. It shouldn’t be a big deal, as long as the advisor previously was providing a lot of value. If they’re no longer providing value, you need to have that conversation with the advisor and move on. Potentially, the advisor has already earned their compensation (i.e. options, vested over a few years) and while the relationship can remain an amicable one, you may need to find new advisors that can guide you through the next stage of your startup’s journey.

I’ve been “fired” as an advisor before. In one case they didn’t use me enough (despite my attempts to reach out.) And in another case, they simply outgrew me. I was happy for them!

Recommendations on functional experts as advisors:

Strongly consider adding functional experts as advisors, especially in areas where you have gaps.

You may find that you leverage this type of advisor very actively, to the point where they’re doing work for you; if that happens, they may be moving into more of a consultative role (in which case you can explore alternatives in terms of compensation; i.e. pay them.)

Functional experts don’t have to stay as advisors forever. Once they’ve helped you solve for the specific functional challenges you’re facing, it may be time to break up, and that’s completely fine. The best advisors will get it. They’ll be excited that the Padawan is now the Jedi.

How to maximize the value of your advisors

Adding advisors shouldn’t be done quickly or flippantly. And similarly, advisors shouldn’t move too quickly to become official advisors either (if they do, it’s not a great sign.)

1. Get to know them first

This sounds obvious, but I know quite a few founders that move too quickly to secure advisors because they think it’ll be a significant boost in credibility. It’s not. This is especially true with “celebrity advisors.” Somehow you get connected to them, have a quick call, they agree to (lightly) lend their name to you and your business (they’re likely advisors to a lot of founders!) and you feel great. Then you never hear from them again…

Ideally your advisors are people you know, trust (duh!) and have worked with in some capacity before. That may not always be the case, because this means people without great networks will struggle to find quality advisors, but it is a relationship business.

My suggestion when engaging with someone you don’t know well is to build up the relationship first, meet with them a number of times, ask them for help (prior to them becoming official advisors) and see how the relationship goes. They should be willing to do that in exchange for nothing, because they like helping. At some point, if they’re creating value, the relationship is being built and there’s trust, you can move to the next stage and ask them to become official advisors.

2. Do your due diligence

Even if you know the potential advisor you’re looking to bring on board, I would suggest you do your own due diligence on them. Find others they’ve worked with and see what they’re like. In StartupLand so much is built on reputation, but those reputations can be superficially good, and then less good when you scratch through the veneer.

I “know” people in the ecosystem and think they’re awesome from what I’m seeing; but I don’t “know know” those people. We haven’t gone into the trenches together. Their reputation seems good, people clap a lot when they do presentations, but what are they really like?

Find out.

3. Avoid “professional” advisors

Part of the reason people are skeptical of advisors and their value is because there’s a decent number of people who are “professional” advisors.

They’re essentially out there hawking their advisory capabilities to many startups. They have a small army of startups they’re supporting, which is basically impossible to do well. Imagine they’re working with 20 startups as an advisor, and they’ve agreed to meet each one monthly for 1 hour. That’s 20 hours per month! That’s a lot of time to commit (assuming they have other jobs)—which likely means they’re simply not delivering enough value.

A lot of people feel this way, because they’ve worked with “professional” advisors that seem to be everywhere. They’ve leveraged their reputation and influence to become advisors to a ton of startups. Do you really want to be 1 of 20? 1 of 50? You’re not going to get real value.

Simply put: Ask a potential advisor how many founders/startups they’re working with, and then decide if you want to be another one.

4. Define the advisor’s obligations

You need to set clear expectations with advisors on what you need from them. This will vary based on the type of advisor.

The easiest thing to figure out is the frequency of the engagement and how you expect to communicate with an advisor.

Are you scheduling regular meetings? (Note: This can be done with a group of advisors at the same time too, or individually)

Do you have the advisor on “speed dial”?

Is the advisor in your Slack?

Next you should explore deliverables. What are you expecting the advisor to actually do?

Perhaps you’re simply looking for advice (when you need it.) That’s fine, but you shouldn’t hesitate to dig deeper. For example:

You could ask a sales expert advisor to sit in on sales calls with you, or listen to your sales calls and provide feedback

You could ask a product management advisor to meet with your team monthly to see how things are operating, and provide recommendations on improving how they build and ship product

You could ask an advisor to hold a workshop for your whole team on culture, or participate in an offsite

You could ask an advisor to make X introductions to potential partners in your industry

And so on…

The key is to define the actual expectations and deliverables you’re looking for.

At some point you may “cross the line” into having an advisor that’s also a consultant (i.e. doing fairly active and regular work with/for you), in which case the discussion on compensation may change (more on compensation later.) But if you don’t define the expectations and deliverables, there’s no clarity around what you’re looking for and what the advisor is willing to do.

I would suggest adding deliverables & expectations into your advisor agreement (you will need to have a legal agreement with advisors to cover things like confidentiality, compensation, etc.) You can add a section on responsibilities. (If you find you’re not getting what was agreed to, you can fire the advisor.)

Should you include advisors in my pitch deck?

Shrugs.

As an investor I’m ambivalent to seeing a list of advisors in a pitch deck. I’ve never thought to myself, “I’m going to invest BECAUSE of that amazing list of advisors.” And a list of advisors has never tipped the scale for me from a “no” to a “yes.”

The impact of advisors in your pitch deck is minimal. A fair number of investors don’t like seeing advisors in pitch decks at all. They feel it’s a thinly veiled attempt at signalling that you’re “hot shit.”

Note: There are exceptions to every “rule.” Biotech or hard tech startups benefit from having a “scientific advisory board” because they’re dealing with something that’s so complex. The engagement level from that advisory board still matters; simply name dropping isn’t going to cut it.

Here are a few recommendations if you are going to include advisors:

Don’t have too many. If you have more advisors than team members it makes the Team slide awkward. My suggestion: Pick a few advisors (literally 3 or less) that you think a specific investor would find interesting and customize your advisor list accordingly.

Consider putting them in the appendix. Most pitch decks have an appendix, or a follow up / more detailed deck—this is a good place to put advisors. It also gives you the opportunity to go into a bit more detail on what those advisors are doing for you, so they don’t come across as “figureheads.”

Make sure advisors are ready to speak with investors. If I see an advisor in your pitch deck that I know, I am 100% reaching out to learn about you and your relationship with them. Don’t put any advisors in your pitch deck unless you’re absolutely sure they’re going to say good things. And by “good things” I don’t mean, “Oh ya, she’s a great founder,” I mean, “Oh ya, she’s a great founder, we meet weekly to discuss key issues in the industry, and I’m actively supporting her with introductions.” There needs to be proverbial meat on the bones of your relationship with those advisors or you will lose a lot of credibility.

How to compensate advisors & should they be required to invest?

“To equity or not to equity, that is the question.” - Startup Shakespeare

Aaron Dinin wrote a blog post entitled, “There’s One Thing No Good Startup Advisor Will Ever Ask For”, in which he argues that no good startup advisor would ever ask for equity (or options).

I disagree.

His argument is that the best advisors should be investors and willing to put “their money where their mouth is.” Otherwise it’s bad signalling (primarily to future investors.) Aaron does make some great points, and I agree that there are a lot of “advisor sharks” out there asking for 0.25%-1% of your company in exchange for the grace of their presence (who don’t invest, even though they could.) But I don’t think things are so black and white.

He also suggests that instead of requiring an investment from advisors, you can ask them to commit to the next financing round.

“How about I commit to investing in your next round?” I told her. “By agreeing to invest in your next round, then you’ll have an advisor who’s spent a long time working with you and is so confident in your success he’s also willing to put his own money in. That’s a great signal to any investors.”

I think this is interesting, but I don’t get why, as an angel investor, you’d wait to invest at a higher valuation in a subsequent round instead of investing right away. Perhaps you’d do this if you weren’t quite ready to invest (b/c you don’t believe enough in the company yet) and you believe your help as an advisor will get them to that point, but I’m not sold on this approach.

Here are my thoughts:

You should compensate advisors with equity (options to start). Typically this falls into the 0.25%-1% range; leaning more towards the lower end.

The options should vest over 2-3+ years, essentially over the length of time you believe the advisor is going to provide real value (if they continue to be an active advisor after that, you can consider providing them more options). Note: If while vesting an advisor is no longer valuable, let them go and save the options.

If you’re paying advisors cash, I would consider them more consultants, and you better make sure the deliverables I described above are crystal clear (otherwise this becomes very sketchy, very fast.)

Advisors don’t have to invest. It’s great if they do, because it’s creating a more shared risk model, and it is a signal they believe in you, but the reality is that not all advisors can invest. This could be a financial limitation (although you can take $1k-$5k from an advisor, so the cheque size doesn’t have to be big.) But it could also be a legal limitation (i.e. some corporate executives aren’t allowed to invest in startups, or at minimum require permission; VCs are often not allowed to invest outside of their funds; etc.) So there are legitimate reasons why advisors can’t always invest, which I don’t think provide negative signal.

I’ve never heard of a downstream investor really poo pooing a deal because of advisors that hadn’t invested. I’m sure it’s happened, but there are lots of other reasons not to invest in a startup. Having said that, if you’re hyping your incredible advisory board and I know they’re also investors, I will ask, “Did they invest?” So I get Aaron’s point, but I don’t think it’s a deal breaker.

Sometimes a nominal check from a prominent angel investor can have a negative impact. I know of several well known people who invest nominal amounts in startups and then go around bragging extensively about how prolific they are as angel investors. I can guarantee you these people are doing this because they don’t want to invest significant capital but they want advisor upside—so the 0.25%-1% they’re getting as an advisor significantly dwarfs the options/equity they’re getting from investing. But they invest anyway to brag about the size of their portfolios.

Note: I’m not suggesting any size cheque/investment should be diminished. Every dollar is important. But it’s the “I’ll invest if you give me upside as an advisor” shtick that quickly becomes cheesy.

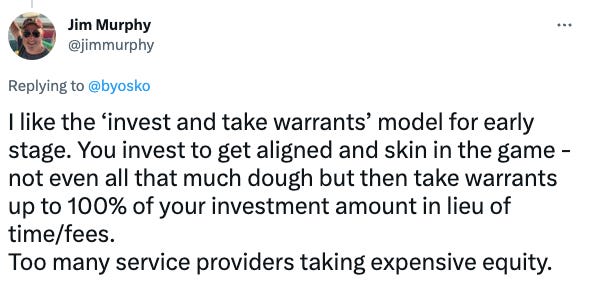

Jim Murphy proposes an alternative to the “I’ll invest $X, and then you’ll give me a disproportionate amount of options/equity” through the use of warrants:

If you’re not familiar with warrants, read this, Warrants vs options: Everything you need to know. The definition of a warrant is:

“A warrant is an agreement between two parties that gives one party the right to buy the other party’s stock at a set price, over a specified period of time. Once a warrant holder exercises their warrant, they get shares of stock in the issuing party’s company.”

What Jim is also pointing out is that the value of the warrants shouldn’t exceed the value of the investment. So if you invest $5k, you’ll get $5k worth of warrants. Often with options that’s not how it works, and the advisory options are worth much more than the actual investment (this is OK, but it can be abused by predatory advisors very quickly.)

My approach to being a Founder (startup) Advisor

I am currently an advisor to a few founders. I’ve been a founder advisor for a long time. Here’s how I approach it:

I’m never advising more than 3-5 founders officially. I take my advisor duties seriously and never want to overcommit. I’m open to helping lots of founders, and often will have one-off meetings with people, or even a few meetings with founders ad hoc (when they reach out), without becoming an official advisor.

I won’t become an advisor to founders I don’t know. This sounds obvious, but I know a lot of startup advisors do this. I’d rather meet with a founder a number of times, get to know them, ask about them through my network (and I expect they are doing the same!) before getting into an official, contractual relationship. I don’t want an investor calling me to ask about a founder, and my response is, “I don’t know them very well, but I liked their idea, so figured I’d help out.”

I do expect to be compensated with options/equity. If you believe I can genuinely increase your odds of success, I think it’s only fair that I’m compensated should you be successful. If you’re not willing to give me that, I don’t think you’re committed enough to working with me (which is totally fine, but then I shouldn’t be an official advisor!)

I want to schedule regular check-ins but also enjoy being “always on.” Regularly scheduled advisor meetings are good—founders can set an agenda, prepare, and they’re usually quite productive. But I’m an “always on” kind of person, be it via email, text, WhatsApp, Slack, etc. Shit happens constantly for founders, and they need someone to bounce an idea around, a shoulder to lean on, a quick introduction, etc. I enjoy being available to founders.

I’m completely fine being fired. If I’m no longer providing value to a founder, I’ll encourage them to fire me. I have no interest in being a “hanger-on” that’s vesting options without earning them. Or if I’ve already fully vested my options but I’m not useful anymore, I’m perfectly OK with the founder finding other advisors that can be more valuable. There’s no room for passengers when building a startup.

I’m always founder first. I believe the most valuable thing I can bring to the table is being there for founders at an emotional or personal level. I’ve lived the ups and downs of building startups, I know what that rollercoaster feels like. I’m a “founder first” kind of person. While I do have expertise in a few things (product management, analytics, fundraising) I think I’m most helpful just jamming with founders about the overall experience. And no matter what happens (beyond fraud, deception or other really shitty things), I’m backing the founder.

Should you have advisors?

Yes.

Advisors can be extremely valuable. But don’t collect them like Pokemon. Don’t go for big name advisors because you think it’ll make you and your startup look cool. It might, but it won’t last.

These are meant to be serious, trusted relationships with people you can rely on to help you in almost any circumstance.

You should also consider if an advisor should be a board member. Board member responsibilities are more significant—board members have a fiduciary responsibility to the wellbeing of the company (which doesn’t always mean they’re in your corner.) If you look at your best advisor, the one you trust the most, the one that provides a ton of value, and the one with the right experience, you may invite them to become an independent board member.

Find advisors that are founder first—i.e. they’re not there to squeeze you for upside (although you should compensate them), and even when the shit is hitting the fan, they’re still there for you even if they know their options/equity are going to zero. When the house is burning and everything is crumbling around you, do you picture your advisors being there for you still? ← Find those people.