How To Pick the Right Venture Studio

Founders: What should you look for when joining a venture studio? (#65)

As more venture studios emerge, it will become increasingly challenging for founders to pick the right one. Recently a few founders have asked me:

“How do I decide if this is the right venture studio for me? Is this a good deal? Should I start a company with this studio?”

Let’s dig in…

1. What Areas Do They Focus On?

I believe the future of venture studios is vertical. The most successful venture studios will be experts in something. It may start with an industry focus, but many studios will specialize further.

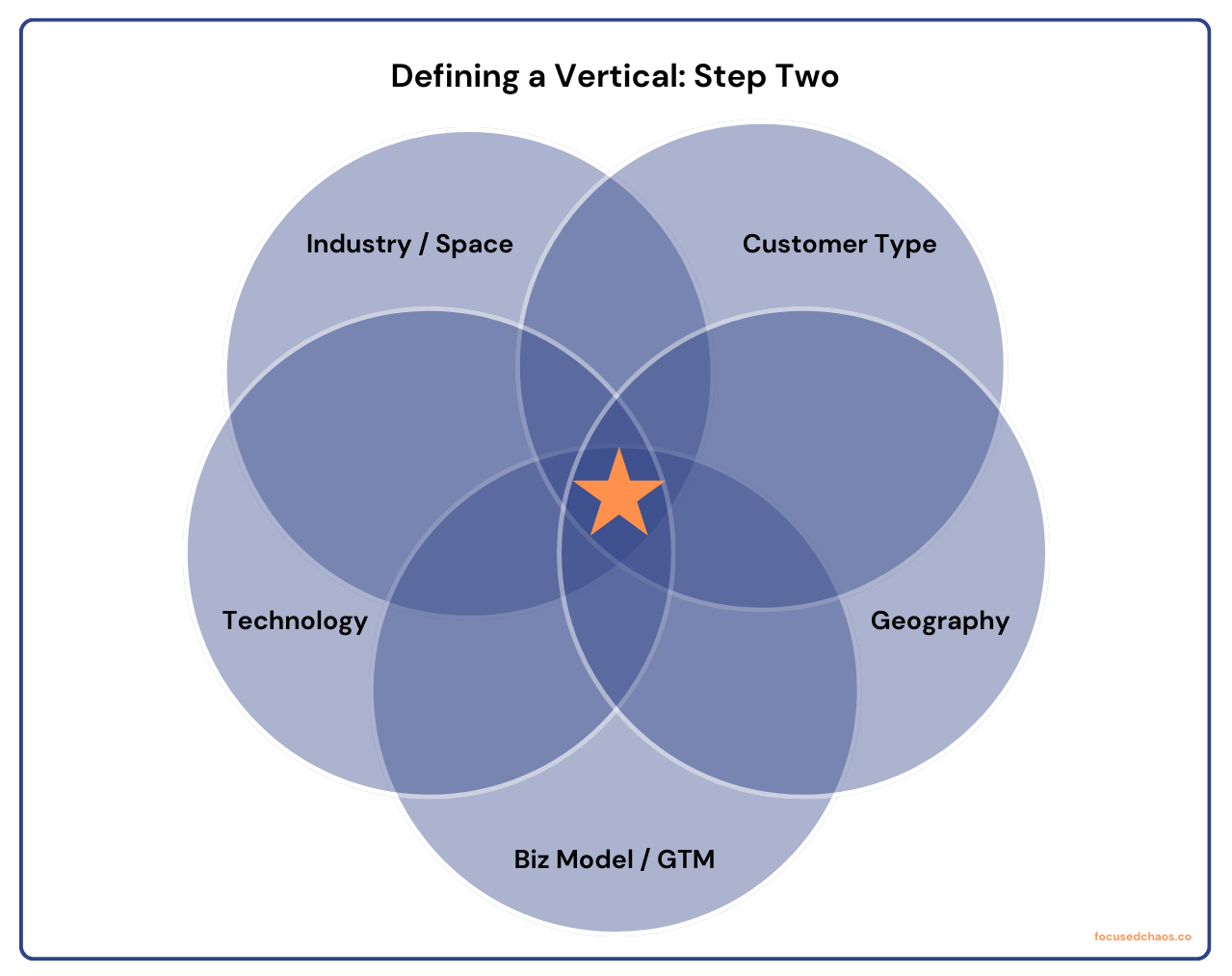

Here’s how I define a vertical:

When picking a venture studio, dig into each of these and figure out if there’s alignment with what you’re interested in. You may be committing 5-10 years of your life to your new startup, it’s important that you’re on the same page.

Do you want to spend 5+ years of your life building a startup in the B2B enterprise sustainability space?

How about 5+ years in B2C mobile gaming in Asia?

Find a studio that specializes in building startups in what you’re interested in. The more specialized the better, because it should increase the odds of success.

2. At What Stage Do They Recruit Founders?

Studios recruit founders at different stages. I’ve written about this previously (When to Recruit Founders into Your Venture Studio) but for founders reading this, let’s simplify:

The beginning: You may get recruited by a venture studio before any real validation work is done; some studios recruit founders with ideas, others don’t require that you have an idea.

The middle: You may get recruited when a venture studio has done their own validation work and now has more conviction about the opportunity, but they haven’t built anything yet. In this case it’s their idea, and they’ve been working on it for ~3-9 months.

The end: You may get recruited when a venture studio has done a lot of validation and is now incorporating the company. They’re installing you as CEO. They may have already built an MVP (or it’s in progress), and they have initial customer traction.

The timing of founder recruitment impacts a lot. Let’s tackle three things:

Where the idea comes from

Contractual agreement

Founder vs. operator approach/mentality

Where the idea comes from

If studios recruit founders at the beginning they may be open to you bringing your own idea to the table. Studios that only recruit in the middle or at the end aren’t looking for ideas, they’ve already done a bunch of validation work on their own.

Most of us agree that ideas don’t matter that much—they’re a dime a dozen, and it’s really about the validation and execution. But we’re lying to ourselves. People love ideas. People get hooked on them. And the originator of the idea impacts the relationship.

If a founder joins a venture studio with an idea, they’re often more reticent to change it. “It’s my idea, I came up with it and I know it’s good!” They dig in their heels and can be more difficult to work with. In my experience, they also believe they deserve more equity and better terms from the venture studio because they’re bringing the idea with them.

If a founder joins a venture studio without an idea, the most common question is whether or not they’re truly passionate about the idea they’re “given.” Future investors often think like this. They want to know that the founder is ultra-committed to what they’re doing, and most of the time they’re betting on founders that had the original idea. It turns out most people have a bias towards the originator of the idea being the best person to build the company. Personally, I believe people can get excited and passionate about ideas that aren’t theirs, or can work collectively with others (i.e. a founder collaborating with a studio) to uncover an opportunity that the founder wants to dive into.

Contractual agreement between venture studio and founder

The timing of joining a venture studio significantly impacts the contractual relationship you have with that studio.

If you’re joining very early, before any work has been done, the studio is most likely hiring you as a contractor (title: Founder in Residence or Entrepreneur in Residence). This is often the case when they recruit a founder in the middle of validation as well (they’ve done some work, but it’s still early). A few things to consider in this case:

They should pay you, although it’s not going to be a “market rate” (if you were getting a full-time job somewhere)

The intent is that it’s temporary (~3-9 months)

You should negotiate what happens if you find a startup worth building (i.e. don’t wait until the end of the process to figure out how you’re going to build a startup with the studio)

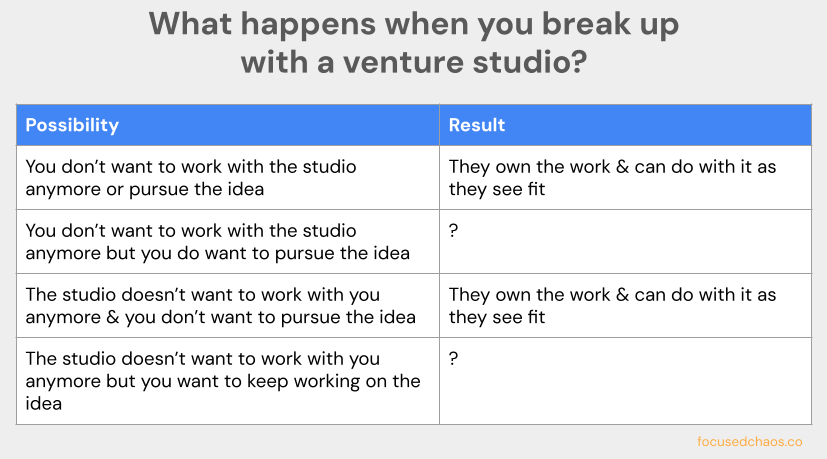

You should also negotiate what happens if you “break up” and go your separate ways. There’s a good chance they own the work (and “intellectual property”) that was created while you were working for them as a contractor. This makes sense, but it gets sticky if you brought the idea into the studio. It also gets sticky if you want to keep pursuing the opportunity but they don’t.

If you’re joining when the new startup is incorporated, things are simpler. You’ll be the CEO / founder of the startup and employed by the new entity. There’ll be an employment agreement and other agreements that you have to understand clearly, so you know what you’re getting yourself into.

Founder vs. Operator

If you’re recruited into a venture studio earlier, the sense is that they’re looking for a true founder to validate an opportunity and build a company. If you’re recruited later—especially once an MVP is built / early traction is secured—venture studios may be looking for more of an operator (even if you’re given the title “founder.”)

What’s the difference?

I like how Richard Li, CEO/founder at Amorphous Data describes it in his post, Founders, Builders, and Operators:

“Founders come from all backgrounds: technical or business; Harvard MBA or college dropout; industry veteran or self-taught technical hacker. But all founders need to have a certain amount of hubris. After all, a founder needs to believe that he can succeed — when a rational evaluation of the situation will find more reasons for failure than for success. A founder needs to believe that he can be successful at sales, marketing, board management, product development, regardless of past experience. A founder needs to believe that his idea is truly worthwhile, and better than the other choices the market has and will offer. A founder needs to believe that he can drive the company to prosper, even in the face of better capitalized competition.

If the builders and founders do their jobs well, a clear, sustainable business model and strategy takes shape. The management team has evolved a working cadence and has proven its ability to execute. It’s time to step on the gas.

You need operators.”

Generally, founders are seen as the “crazy ones” — the passionate leaders that will do anything and everything to win. Operators, meanwhile, take something that’s already working and operationalize it in order to scale (and do so successfully). Founders may chase shiny objects and get caught in the hype, operators execute plans.

Founders come in all shapes and sizes. Yes, you’ve got the visionary leader that evokes Messiah-like vibes as they march towards creating a new world order. But you’ve also got much humbler leaders, builders, people who don’t need tons of attention or hype, people who want to solve real problems & build great businesses.

Denis Shafranik, Managing Partner at Concentric, calls this person the Operator Founder. In his post from May 2021, The Rise of the Operator Founder, he wrote:

“Many founders were forced to pivot their focus overnight, shifting from growth mode, investor pitching and media interviews, to cost cutting, firefighting, and rapid decision-making. A laser-focus on operational detail was required, and those who failed to adapt their approach, quickly found themselves exposed.

But, while 2020 was a one-off (hopefully), the rise of operational skills, and ‘operational founders’, is part of a wider trend. While in years gone by, VCs were frequently won over by smooth, well-pitching ‘salesperson’ founders, rising economic and business uncertainty means there is now greater demand for entrepreneurs who can keep costs under control, manage risks, and achieve profitability, rather than charm and hype things up. Now it’s time for operational founders to shine.”

The Operator Founder is an excellent profile for venture studios.

As you explore which venture studio you want to join, you’ll need to decide if you want to be a founder or an operator. One isn’t better than the other, they’re just different. But if you join a venture studio with the impression that you’re a startup founder and they actually want an operator (or vice versa) it won’t work.

3. What Resources Do They Provide?

Venture studios are meant to build and fund startups. Before joining one, dig into what they’re really offering and the work they’ll do with/for you.

People & Services

Venture studios need to roll up their sleeves and do work. They are an operational co-founder that should be building the startup with you. You need to understand what resources they have and how to access them.

Do they have product managers, designers & developers to build an MVP?

Do they have marketers that can help with growth, social media, brand building, etc.?

Do they have specialized resources that you may need (i.e. data scientists, AI developers, videographer, animator, etc.)?

Do they have a recruiting team to attract a co-founder and/or talent to the new startup?

Do they have bookkeeping, accounting and/or legal services?

Do they proactively introduce you to potential investors?

Etc.

As a potential founder looking to join a venture studio, you’ll also want to understand if the resources are senior or junior and how you should work with them. For example:

Are you given a small, full-time team that reports to you? Or are the resources shared, and you need to coordinate working with them?

Are the resources senior—people you’d bring in as VP Design, VP Growth, etc.—and they’re providing strategic guidance but not executing? Or less experienced resources that are great at executing but need a lot of direction? And so on.

Capital

Studios should invest money. If they bring you on before incorporating then they’re likely paying you as a contractor. Once the startup is incorporated they should be investing capital into it. A few questions you’ll want to ask:

How much capital do they invest?

What is the criteria they use to make investment decisions?

Do they require co-investors at incorporation?

Do they require the founder to invest? (Founders: If you have the means you should do this.)

Will they follow-on in subsequent rounds? How many rounds? Under what criteria? If they don’t follow-on, how negative a signal is that for other investors? (This is one of the challenges with VCs building startups—they want to get in early, but if they don’t back you in subsequent rounds, you may find it very difficult to get other investors on board.)

Are they able to bridge your startup if it doesn’t get sufficient traction to raise a follow-on round?

Etc.

Venture studios have to balance between the resources they provide (and pay for) and the capital they invest. Some will invest more time, others will invest more capital. Every studio should provide both in some capacity—you’ll want to find a venture studio that provides the right mix for you.

Network

This is a broad bucket, but essentially “Network” refers to the studio’s connections and access to anything and everything else you might need. For example:

Customers

Partners

Investors

Service Providers

Etc.

In a vertical venture studio these resources should be more apparent. Ultimately for your startup to succeed you’ll need all of these resources, so figure out how systematically structured the studio is in providing them.

Resources Before and After Incorporation

It’s important to understand resource allocation before and after incorporation, because this changes for many venture studios. For example, they may provide more people resources (i.e. time investment) before incorporation (when you’re validating an opportunity), and after incorporation they invest capital but spend less time. Or they may incorporate early, but not invest a lot of capital out of the gate, instead covering basic expenses through the studio. Some studios will also charge the startup for services, once the startup is setup, which becomes part of the venture studio’s business model (more on that in a moment).

4. What does the cap table look like?

One of the biggest issues with venture studios is the cap table. Many people believe venture studios take too much equity in exchange for what they provide.

A lot of venture studios are in the 40-50%+ range. This feels high, but it depends on what they’re providing. If they’re investing $2M at the outset and you don’t have to raise until you get to a Series A it might be a great deal. So you can’t simply look at the cap table without aligning it to the value the studio provides.

Some studios take 75%+ which is definitely high. These venture studios are most likely looking for operators, need to provide a lot more support (for a longer period of time) and aren’t looking to build industry-changing mega-companies. Instead they’re looking for quick wins—early exits at healthy multiples that can be done quickly. This is a completely viable business model, and for a founder/operator getting 10-15%, it can be life changing too.

Beyond the % of equity being taken, you need to understand the terms.

What rights does the venture studio have as a co-founder?

What rights do they have as an investor? (These rights are usually more significant.)

You need to understand the structural details of any deal. It’s the same when working with VCs—you have to understand everything that’s in the term sheet (and final paperwork) so you know what you’re “giving up” in exchange for capital. Studios will be all over the map in terms of rights; some will be simple, others will be onerous. Make sure you get a lawyer to review any contract with a venture studio so you truly understand what you’re getting yourself into.

5. How do they make money?

Founders should be aware of how venture studios make money. The most important thing to understand is if the studio takes a chargeback for the services they provide. Many studios do this to fund operations, including the people/resources they’ll deploy to help you.

Here’s how a chargeback model works: The venture studio invests $100 but then requires that you pay back $50 in exchange for services. (I don’t have data on the average chargeback costs related to investment dollars, but I’d guess it’s between 20-50%.)

The amount paid back isn’t always fixed, but it may be (certainly pre-incorporation)

Post-incorporation, the studio may have a rate card they use to charge you if you use their services (but you’re usually not obligated to)

It’s unlikely you can get out of paying them through the chargeback model, although it’s possible you need less services and can negotiate this a bit (but remember, a studio has bills to pay no matter what)

Studios do this so they can invest a bigger amount for equity, but also generate revenue for themselves.

Many studios will raise capital to fund operations. This is completely reasonable, but as a founder you want to make sure they have enough runway to survive. It’s not impossible to imagine a venture studio doing a deal with a founder, committing 6-12 months of resources and capital, and then struggling to pay its own bills and potentially even shutting down. There are 900+ venture studios out there—they’re not all viable businesses. Quite a few will fail, and as a founder you don’t want to go down with the ship.

6. What’s their success rate so far?

Most venture studios are fairly new, so they’re not going to have a lengthy track record. While exits (and cash on cash returns) will ultimately define a successful studio (or not), there are other things you can look at.

For example, venture studios are supposed to expedite the process of building & launching startups. Here’s a visual from Vault Fund, which invests in venture studios:

This isn’t representative of every venture studio, but it’s suggesting that venture studios are supposed to build & launch startups faster and get them to meaningful traction in less time. You can evaluate this for any venture studio you’re interested in.

Most startups going through a venture studio will require capital (from VCs or alternative sources). Another thing you can vet is whether or not a venture studio has successfully helped its startups raise follow-on capital.

So:

Is the venture studio producing good-quality startups faster than the traditional model?

Are a high percentage of those startups able to raise follow-on capital as they leave the venture studio (which can be a sign of “quality”)?

Finally, you should absolutely try and understand the exits and returns generated from any studio you’re interested in. But go a step further and see if the founders of those startups got a return for themselves. A return for the studio isn’t the same as cash in your pocket.

Venture studios won’t necessarily reveal this information with a ton of detail (most of it will be protected by NDAs / legal agreements with acquirers, etc.) so you need to do your own due diligence. Reach out to founders that have exited with a venture studio (you don’t have to ask for referrals, just do it) and hear firsthand from those founders what the experience was like. Reach out to founders that are still in the venture studio and learn what that’s been like. It’s up to you to do your own research & due diligence before committing to join a venture studio (the same is true when raising from investors). The more homework you do, the better off you’ll be.

7. Do you like them?

In the end, a venture studio is a co-founder & partner. They’re going to be borderline impossible to get rid of, and you’ll be working with them for ~6-12 months very actively (and potentially another 2-5+ years after that).

You have to ask yourself, “Do I want to co-found a business with these people?”

That’s what you’re actually doing when you join a venture studio. Don’t take the decision lightly.

You don’t have to be best friends, but you do need to respect the studio and fundamentally believe in the value they’ll create. You have to believe you’re better off with them than without them. You have to trust them. If any of these things aren’t true, the deal & experience will likely go sideways and that hurts everyone.

In a race to build a startup it might be exciting and appealing to jump in headfirst with a venture studio and roll the dice, hoping things will work out. They might. But if they don’t, it’s going to be rough. Breaking up is hard. So take your time getting to know the people running the studio, work with them before committing, ask others in the ecosystem about them and make sure you’re going in eyes open.

Here’s a worksheet that takes this article and breaks it into specific questions that you can use to start evaluating venture studios: Get the Worksheet. ← view/copy/download here.

It’s free to use and copy. I hope it’s helpful for you as you’re exploring the venture studio model.

Great analysis. A worksheet to fill out would be really helpful for founders in this dating phase-including helpful interview questions they should ask!