Plowing Through Conventions: Lessons from a Mexican Agribusiness Startup

The story of Verqor, its founders and how they build a great company. (#71)

I met Hugo Garduno in 2018. He had recently started Verqor, a fintech startup helping Mexican farmers with credit. Verqor was accepted into the 100+ Accelerator’s first cohort with AB InBev, because AB InBev was looking for solutions to help smallholder barley farmers access better financial products. Verqor matched a very specific priority for AB InBev. I was working with AB InBev to design, launch and run the accelerator program.

At the time Verqor was very early stage and had not yet launched. It’s rare for big companies to work with such early stage startups, but it happens.

Lesson #1: Put yourself out there, otherwise you’ll miss opportunities

Whether it’s applying for an accelerator, cold emailing an investor or dialling for dollars with potential customers, you won’t win if you don’t try. Too many founders sit behind their computer screens waiting for things to happen. Hope isn’t a strategy (despite the need for plenty of hope to survive the startup grind).

Hugo applied to 100+ Accelerator on the last day applications were due, because he had just heard about the program. He went for it, with very little to go on. That’s what founders do.

Cheesy, but true.

Hugo’s original idea for Verqor was to help farmers purchase farm equipment together. The assumption was that individual farmers couldn’t afford the equipment on their own and their farms were very small so they wouldn’t need the equipment at the same time. Hugo felt that “group sharing” of farm equipment could help. Better equipment should lead to higher quality & bigger yields, make the work easier and increase revenue.

Verqor kicked off their pilot working with barley farmers, but in truth, they didn’t understand the pain points of farmers (or the other stakeholders) deeply enough.

The big problems were clear, but Hugo and the team had to dig deeper.

Lesson #2: You have to understand more than the obvious problems

Over 90% of farmers in Mexico have no access to formal banking and many live below the poverty line1. Meanwhile agriculture is vital to the country’s economy, employing ~11-13% of the labor force2 and contributing over 3% to GDP3.

Verqor led with a solution—group equipment purchasing/financing—but then realized they needed to really understand a “day in the life” of farmers and the underlying pain points.

In 2018, during the 100+ Accelerator, we introduced Hugo to a few key concepts around problem validation. The fundamental questions and lessons from then remain true today:

How do you identify your customer’s specific pain point (what’s behind the obvious problems you can Google and everyone understands)?

How do you understand customer’s functional challenges, but also their emotional and social problems (and influences)? What’s underneath the problems they’re experiencing?

How do you determine the right (and narrow) ICP (ideal client profile)?

Anyone can find mega trends or “universal truths” and say, “That’s a problem, I’m going to fix it.” Unless you dig deep and really understand the problems + who has them, you’ll fail. Mega trends and universal truths don’t unlock true insights from which you can build a business.

During Verqor’s initial pilot they realized that group purchasing of heavy farm equipment wasn’t the right place to start. Farmers needed the equipment at the same time, and the logistics for moving large equipment into rural areas was too complicated and dangerous. Plus, the equipment is very expensive, which means Verqor was giving out big dollars, and then having to collect from too many people. The whole thing was too messy.

I like how Paul Graham (co-founder of YC) puts it:

In this case he’s talking about pitch decks, but the key is this: “tell me you noticed something that might turn out to be an overlooked opportunity.” That’s what finding a true insight is all about; you notice something others haven’t (because of the research/digging you’re doing) and that becomes a foundational aspect of what you build from.

Lesson #3: The key principles of startup validation work in combination with the founder mentality

You don’t need to be an innovation framework zealot to go through the process of validating a startup. In fact, if you are a process zealot you’ll fail, because you spend more time verifying that you’re following the process rigorously, versus focusing on the outcomes of the work.

A lot of founders get enamoured with Lean Startup, Design Thinking, Jobs to be Done, etc. and hope that by following a checklist they’ll win. Startups don’t work that way, they’re too messy. But there are some valuable basics you need to get:

Understand how to identify the riskiest assumptions (and why it’s important). This helps structure your approach to validation. DVF (Desirability - Viability - Feasibility) is a helpful framework. Hugo had made assumptions on the problem and solution, jumping ahead into a pilot before doing enough validation.

Understand rapid experimentation/testing to execute faster. A startup’s only real advantage is speed. Lean Startup’s “build → measure → learn” framework makes sense; it’s a cycle you want to go through as quickly and frequently as possible to get answers. For Verqor, running the initial pilot turned out to be very time consuming. They had to meet with groups of farmers in remote areas; get enough of them on-board; vet them all; finance and deliver the equipment; track progress during the planting/harvesting season; get their money back. It was a big bet type experiment. Hugo realized there were faster ways to learn and experiment.

Process alone won’t get you to the win. You need to balance the right approach with the right mindset:

Without some understanding of how to execute problem and solution validation, you’ll rely too heavily on your own instincts, or just run ahead blindfolded.

Without a founder’s level of determination, grit and perseverance, you’ll give up when the shit hits the fan (and it always does).

After running the initial pilot, Hugo and his co-founder Valentina, understood that financing group equipment purchases was too complicated. Instead of giving up, they iterated and kept trying. This is the moment where they demonstrated the “X-factor” of a true founder—they chose to push forward, emboldened in their belief that they would figure out how to help farmers. They didn’t chase different shiny objects or say, “This is too hard to figure out let’s do something else.” They persevered.

How does early startup validation work?

Here are a few articles that can help you through this journey:

How to Apply the Scientific Method to Startups Without Being a Zealot

Test First, Build Later: A Guide to Validating Your Ideas With Stimulus & Prototypes

If you’re looking for books on this topic, you can’t go wrong with:

The Lean Startup by Eric Ries (still an all-time classic)

Talking to Humans by Giff Constable

Running Lean by Ash Maurya

Lesson #4: You have to understand all the stakeholders

Nothing is ever done in isolation. Everything is part of a bigger system that involves numerous stakeholders. Farmers don’t grow crops without inputs (i.e. seeds, soil, fertilizers, biologicals, etc.) Farmers need buyers, otherwise there’s no point growing anything. The entire agricultural ecosystem is complex, with input manufacturers, retailers, farmers, financial institutions, insurance providers, off-takers, etc. To figure out how to finance farmers you need to understand the entire system.

Hugo began meeting with all the key stakeholders to understand their pain points. What do input providers need when working with farmers? What do off-takers need? What do banks need? Etc.

Through this discovery work, Hugo and the team understood all of the challenges throughout the ecosystem and were able to experiment, learn and pivot towards a better solution.

As important as it is to identify your key ICP and their specific pain points, you can’t put blinders on to everything else. If you don’t understand how your ICP exists & navigates within their ecosystem, you’re missing key data points for understanding problems and solutions. You’ll miss out on potential go-to-market strategies or how the entire system around your ICP may affect your business model.

How do you understand the ecosystem your ICP exists within?

Here are two articles that may help:

Your Startup is a System You Can Map to Identify Problems, Align the Team & Win — This is more focused on how your startup works (all the customer touch points), but there’s no reason you can’t expand that to connect into the broader ecosystem within which you’re playing.

4 Ways to Use Customer Journey Maps Successfully — Another visual approach to mapping how your customer interacts with your solution, but also everything around it.

Hugo learned that banks struggled to provide credit to farmers because default rates are high and collecting is tough. Farmers borrowed money, but didn’t always spend it properly. Buyers weren’t getting higher quality and volume of crops, and had no visibility into what farmers were doing.

Eventually, Verqor built a fully integrated system to bring all stakeholders together.

Lesson #5: Solutions can seem complex in their simplicity

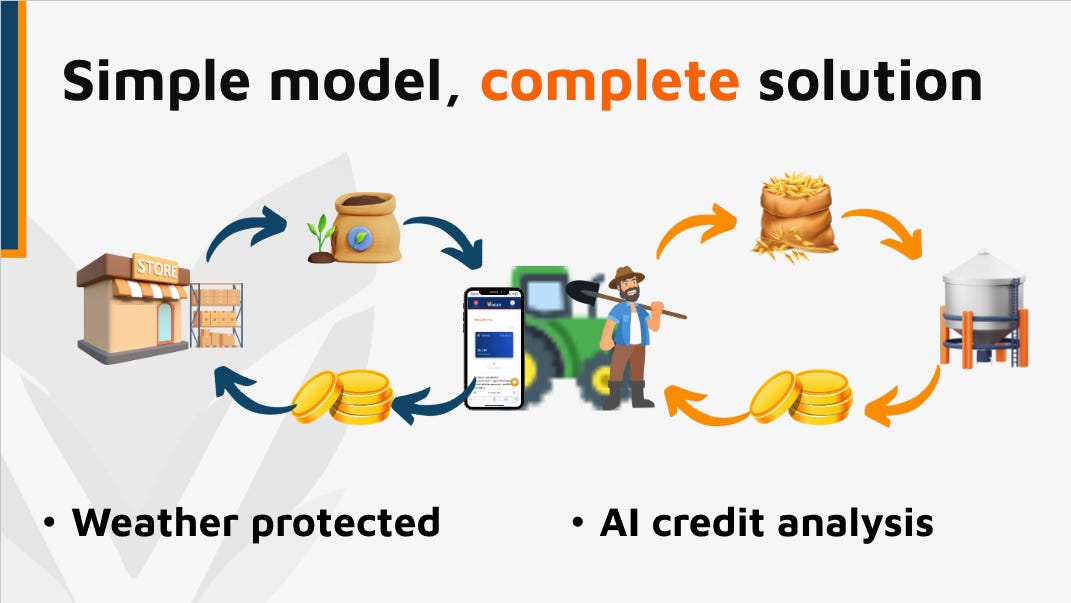

Today, Verqor has built an end-to-end solution for everyone in the agricultural supply chain. Here’s a slide Hugo recently shared with me:

Farmers apply for credit online and get an answer in < 48 hours.

The credit (cashless) is only usable in the app for purchasing inputs (from input manufacturers and retailers).

When the farmer delivers crops to off-takers/buyers, those buyers pay through Verqor, so the loan principle is taken by Verqor, and the rest is given to the farmer.

Every credit offered by Verqor is backed by weather insurance protection.

And as Verqor collects more data, it’s able to build up a credit analysis/score for each farmer that previously was impossible. Over time, Verqor’s credit scoring has enabled farmers to get bigger loans or financing from banks, etc. who previously didn’t have the data to make decisions.

It’s a closed loop between all key stakeholders. Complex, but simple.

How do you define a minimum viable product (MVP)?

Verqor’s MVP (after its initial pilot and pivots) is “big”. It has quite a few features because it’s connecting multiple stakeholders. Hugo and the team had to bring on input manufacturers, retailers, off-takers and the core customer (farmers) at the same time to make the solution work.

That’s what it took.

Some MVPs are complex, others are simple. But everything Verqor built and tested before they got to this point wasn’t the right MVP (or even a real MVP) because it wasn’t a product creating measurable value.

The term MVP has gotten a very bad wrap. I still love it. IMO, there’s nothing wrong with MVPs, you just have to define them properly.

Lesson #6: You have to prove value creation to unlock more value creation

Startups don’t have a chance to scale until they prove value creation for someone. It sounds simple, but it’s not.

Step 1: Solve a problem and prove it. Verqor figured out how to issue credit to smallholder farmers and help them. They did it by building a complete experience for all stakeholders in the ecosystem. As a result, Verqor has an insanely low default rate, which is good for them and their lenders. Farmers keep coming back for credit (and often increase the amount). In one example Hugo shared with me, a farmer received $15,000 in 2019 to rent 20 additional hectares of land. Recently that farmer renewed for $75,000, because he’s expanded to nearly 100 hectares of land.

Step 2: Acquire more users/customers. Once you’ve got something that works and demonstrably creates value, you have to acquire more customers (moving from early to later adopters). Verqor has worked with thousands of farmers in Mexico.

Step 3: Identify additional problems/opportunities you can expand into. As you acquire more customers and get more qualitative and quantitative data, you’ll want to expand what you do in order to create more value (and capture more value for yourself). While Verqor’s core customer remains farmers, they’ve realized the value of the data they have for input manufacturers and off-takers. For example, crop buyers now know everything that’s going into crops, because everything farmers purchase and use is tracked by Verqor. This has the potential to expand Verqor’s business model from lender to data & software provider. In addition, a big percentage of Verqor’s farmers are switching to regenerative agricultural practices (good for them, crop buyers & the planet), because Verqor makes recommendations on the right inputs and farming best practices.

Step 4: Win. You solve a specific problem for a specific group and prove it. You add more users. You expand your capabilities to provide more value to those users (and/or others). You start to validate your business model (the economics) and the potential for scale. That’s what “winning” looks like for early-stage startups.

As you validate and methodically, iteratively prove value creation, it has the tendency to unlock new opportunities. Don’t chase “solve everything for customers” out of the gate, because it’s too complicated and overwhelming.

Lesson #7: You can build startups anywhere

Mexico is not Silicon Valley or New York (and that’s OK!) Great startups can be built there. The same holds true for pretty much anywhere in the world. You don’t have to be in one of the top startup ecosystems to win. Working in a smaller startup ecosystem has its challenges (including all of Canada, btw!)—you won’t have access to the same networks (talent, experts, etc.), raising capital is tougher, and there may be fewer local partners and customers willing to work with you. It’s not for the faint of heart.

But it is possible.

In 2011 I joined a startup in Halifax, Nova Scotia called GoInstant. (If you’re not familiar with Halifax, it’s on the east coast of Canada with ~430,000 people and is not a big startup hub.) The team was insanely talented. We had some hype, which attracted talent to us. Startups in smaller ecosystems can become “big fish in small ponds,” which has its advantages. A year after I joined we were acquired by Salesforce. That acquisition changed the lives of everyone on the team. It wasn’t a billion dollar exit, but it was most definitely material to us.

Don’t get caught in the hype. It’s a trap that makes you feel inferior (unless you’re on the “inside”) and leads to bad decision making.

I remember one of my portfolio companies many years ago being told by a VC, “You’re not growing fast enough, you need to build a new viral app to grow more quickly.” Their product was working, but it was for families and required parents and kids to adopt it. The more people you need to use your solution for value to be created, the tougher it is to pull off. But they had traction—just not enough for Silicon Valley investors. So they built a new app, more game-like, with the goal of growing the user base quickly. The app failed and so did the company. Would they have succeeded had they stayed the course? Maybe, maybe not. But they got caught in the hype, followed it blindly, and failed.

Don’t ignore the big startup ecosystems. The connections there could be hugely valuable. I remember the first time I visited San Francisco in 2008 (as CEO of Standout Jobs). I was blown away by the speed with which people worked (it truly inspired me!) and their willingness to help. I’m still friends with people I met on that first trip.

Verqor is in Mexico because they serve Mexican farmers. You couldn’t build that business without being on the ground. Hugo, his co-founder and the team stay very close to customers, which is the right approach. But they’re also connected to global companies (including AB InBev and others), and they’ve raised capital from people outside Mexico.

Lesson #8: There’s no formula for success

Lots of people share their success stories and “how-tos” for building successful startups. Heck, I do the same thing! 🤣

But the truth is, there’s no formula for success. There’s no perfect playbook that you can execute that guarantees victory. Startups are too crazy. The world is too crazy.

Hugo inspires me because he broke a lot of the “startup rules” that people swear by:

Hugo and Valentina broke many of the “how to build a great startup” rules. But they carefully followed others, especially around how to do customer discovery & validation, iterate quickly and learn. Founders often skip these steps because they’re more interested in building products, they don’t want to be proven wrong and they want to rush forward. Verqor didn’t do that. They tested and iterated their way to a solution that’s creating true value. Hugo and Valentina put aside their egos and said, “Let’s actually try and solve financing challenges for farmers,” and that’s exactly what they’ve done.

Today, Verqor has helped thousands of farmers and their families. And they’re just getting started. I’m blown away by Hugo and Valetina’s determination and perseverance, and can’t wait to see where they take Verqor in the future. I’ve learned a lot from them, and I know many others will as well. 💪

https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2021/04/09/expanding-financial-access-for-mexico-s-poor-and-supporting-economic-sustainability

https://www.economy.com/mexico/agriculture-employment

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1078871/mexico-agriculture-share-gdp/

Wow, what a great story. So different from the classic SaaS!

As someone working in an AgTech startup, I have to say that it is an amazing feat to pull off. There is 0% chance I would have believed someone from outside the industry can do something that complex (and yet, brilliant in its simplicity).

Thank you Ben.