Moving From Problem-Solution Fit to Product-Market Fit

It's far from a straight line and it can take years. Get ready for the ride. (#42)

You’ve built and launched your product.

The next step is proving traction.

With a focus on early adopters.

Your job is getting to problem-solution fit. You need to prove your product is creating value and solving the problem that you previously identified (or another problem that matters more; bottomline, you need to be solving a problem!)

Problem-Solution Fit: What is it? How do you measure it?

Here’s how I define problem-solution fit: You’ve validated a problem and built a solution that fixes it. You know the solution fixes the problem because you have a set of customers that use the product, tell you they get value, pay for it and churn is low. You haven’t jumped from early adopters to later adopters, and your next step is figuring out if you can scale customer acquisition.

Note: A lot of people define problem-solution fit much earlier in the process, prior to building an MVP. I’m a big believer in doing lots of research at this stage, including interviewing users/customers, running experiments with stimulus & prototypes, etc. But none of this is real problem-solution fit, because you haven’t built anything and put it into customers’ hands. The research you do before that is critical, it’ll shape the solution, value proposition, business model, etc. but it won’t prove that you got it right.

How do you measure value?

First, you have to define a “good user.” How do you expect a good user to behave in your product? If you’re building a new calendar tool you’d assume it’s a daily use app (probably multiple times per day) and that’s where you’d set the bar. If you’re building tax planning software, the usage bar is very different.

Usage is a signal of value, assuming they’re using the product in the “right way.”

If they spend a ton of time in the app, but they’re in the help section, something is wrong — that’s not good usage. Since you previously validated a problem (right?) you should have expectations for what “good usage” looks like and be able to use that to define a “good user.”

With your definition of a “good user” in-hand, you can now measure things quantitatively and qualitatively:

Quantitatively: You’re tracking usage to see if people behave as expected. Make sure you instrument your product to track events (this should be part of the MVP) so you can get the right data.

Qualitatively: You’re talking to users regularly to get a sense of how they’re using the product, to collect feedback and gauge if they’re satisfied.

Note: Your definition of a “good user” may be wrong. That’s OK as long as you have qualitative evidence that suggests you can change the definition. You might have assumed more usage than is happening, and as long as you have confidence users are getting value, you might redefine “good user.” That’s why it’s important to blend quantitative and qualitative data together.

Note: A “good user” is not only one that uses your product, it’s one that can drive the business model. Usage has to be connected to how you ultimately intend to make money and scale. Usage for usage’s sake isn’t interesting. You don’t need to prove the economics of the business at the problem-solution fit stage, but you should be able to say, “If people keep using the product this way, it’s going to validate our business model.”

Other than usage, there are other signals of value:

They share the product with others. Your product may not have built-in viral features, but that shouldn’t stop people from sharing the product if it’s helping them. They might invite colleagues to use it, or share with friends, or post on social. People don’t share things easily—they’re putting their reputation on the line and leveraging a portion of their social capital to share your product; if they’re doing so it’s a good sign.

They’re willing to give testimonials or case studies. Similar to sharing with others, people don’t do this willy nilly, especially in a B2B context. Publishing a testimonial or case study permanently connects the user/customer to you.

They write reviews. This is particularly relevant for e-commerce or mobile app businesses, which rely heavily on positive reviews to get attention.

They convert to paid options. They might go from free to paid, or perhaps upgrade from one level to another. People don’t pay for things “just like that” so this is a strong signal that you’re creating value.

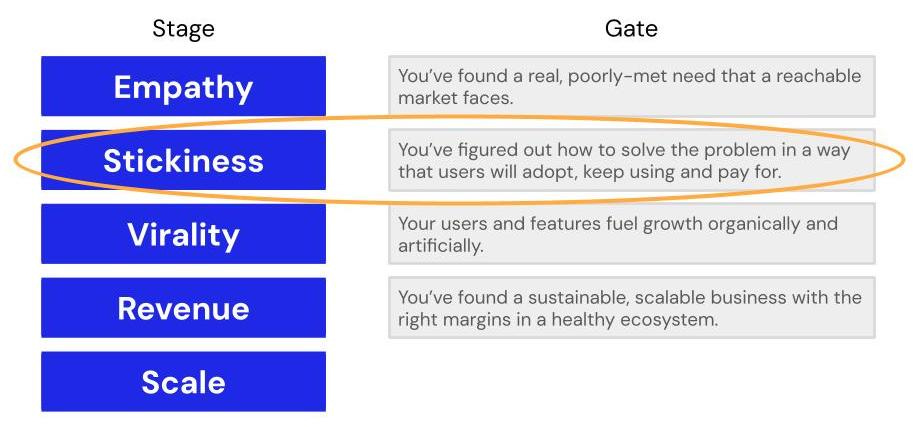

In Lean Analytics, we called this the Stickiness stage.

You don’t need a lot of users/customers to prove stickiness; but you do need a good set of early adopters that you can learn actively from. The actual number you need varies depending on the type of business you’re building. An enterprise software application may only need 3-5 customers. A B2B SaaS tool targeting an SMB vertical? Dozens. A dating app? Hundreds (if not thousands). Marketplaces are the trickiest to figure out because of how they work. You have two sides of an equation that have to balance.

How much time do you spend acquiring customers during this stage?

In your hunt for problem-solution fit you’ll have to bring in new users/customers. Hopefully before you launch you already have a set of users/customers ready to go, but you’ll need to put more through the top of the funnel.

Part of this is to validate your value proposition. If your value proposition is off, conversion to signup (say through a landing page) will be too low. And you can’t get through problem-solution fit without a working value proposition. High conversion doesn’t mean you have problem-solution fit, you still need to prove it through usage, but it’s a great sign. If a market is “pulling” you that’s a good sign that (a) the value proposition resonates; and (b) you’re heading towards problem-solution fit.

At this stage don’t try to optimize customer acquisition, just get enough people through the door that you can iterate your way to problem-solution fit. You’re fully embracing the mantra, “Do things that don’t scale.”

Please don’t blow tons of money trying to acquire customers. At the same time, you shouldn’t focus on customer acquisition cost, because you’ll optimize that later. You’re not trying to prove you can acquire great customers cheaply, you’re trying to prove that people get value from the product.

Getting to problem-solution fit doesn’t happen overnight

It can take months, if not years. There’s a good chance you’ll pivot along the way. And the truth is, most startups fail at this point. They never get through the Stickiness stage because they never prove that they were solving a painful enough problem in a meaningful enough way. I’ve seen many startups pretend they got through this stage in order to scale (and they often raise a lot of capital too!) but eventually things collapse.

The signals you’re getting at this stage might not be perfect or overwhelmingly strong. You’ll have to rely on your gut too. But if you’re wrong, there’s a good chance you fail. If you’re right, you have a shot at getting to the promised land: Product-Market Fit.

Product-Market Fit: What is it? How do you get there?

Ah…product-market fit (PMF). The holy grail of accomplishments, the shining star in a black night of nothingness. If only…if only…

Product-Market Fit is not the promised land

Getting to PMF is a huge step, but it’s not the same as winning.

As clearly as I’ll try to define it (below) there’s still an element of uncertainty, which means you can declare it too early, too late, or never at all and still win or lose; none of this is perfectly well defined with easy to follow playbooks that’ll guarantee victory.

You can get to PMF and then fall out of it or still not be able to scale sufficiently to win. I’ve seen this happen, especially when a startup raises a lot of capital and the expectations go up 100x.

You can hit PMF and still make a ton of mistakes, some of which may prove deadly. Things don’t really get easier as you scale. The problems simply change.

How VarageSale Achieved Product-Market Fit and Still Failed

VarageSale was a hyper-local community marketplace for buying and selling goods. It focused on women (~98% of the user base) selling smaller items (average transaction was ~$20).

I was one of the first investors in 2012. The company had a handful of communities running at the time with off-the-charts usage. I had never seen a stickier product. People were using VarageSale every day, multiple times per day. Even the founders were surprised at the response from users. This was clearly problem-solution fit.

VarageSale acquired communities by moving them off Facebook Groups. It was a singular hack that enabled them to kickstart community growth on their platform. And it worked very well.

I joined the company in August 2014 to run product. In April 2015, VarageSale raised $34M from top-tier venture capitalists including Sequoia and Lightspeed. I can’t remember how many communities we had at that time, but it was a decent number, and usage continued to be incredibly strong (we were at ~40% DAU/MAU, which means 40% of our monthly active users used VarageSale daily.)

I would suggest we had achieved product-market fit. At least it sure as hell felt like it!

We had validated the problem, built a solution that was crazy sticky, and we were growing at a good pace. The new users and communities we brought onboard behaved the same way our early adopters did—they loved VarageSale and used it regularly.

We didn’t have a business model and were hesitant to use advertising (although that’s how many consumer applications monetize.) And at some point Facebook took notice and it became harder to move groups onto our platform.

With $34 million dollars in the bank, you have to spend it to grow. And we tried. Unfortunately we could never figure out how to scale into investors’ expectations, and we couldn’t figure out how to monetize in a meaningful enough way.

We had product-market fit, or something very close to it, but with tons of capital and incredible pressure to 100x everything, VarageSale failed.

PMF is not a panacea. It’s a step on a journey. Heck, PMF isn’t even a perfectly definable milestone that you can say “Mission Accomplished!” to.

So what is product-market fit?

Here’s my definition: You have problem-solution fit and you’ve figured out how to acquire customers in a repeatable, scalable way. The new customers that you acquire are “good customers”—they use the product, get value from it, pay and don’t churn (too much.) They’re behaving similarly to your early adopters.

For more on my definition of product-market fit, please read: You Don’t Have Product-Market Fit (and that’s OK)

Looking back, it’s possible we didn’t hold VarageSale to the standard of my definition:

✅ We definitely had problem-solution fit, validated by the stickiness of the product and the qualitative feedback we collected.

✅ New users behaved similarly to early adopters. As you scale, usage numbers tend to drop, but as long as they’re only dropping a bit, you’re fine.

✅ We had churn, but it was never severe, and we rarely lost communities entirely.

❓We were still able to acquire customers in a repeatable way (FB Groups) but it wasn’t quite as scalable as we needed it to be. And we didn’t have another go-to channel.

❌ People were “paying” with attention (which is a viable way for people to “pay”) but we couldn’t figure out how to monetize that attention.

How do you get to product-market fit?

The first step towards PMF is growing your user / customer base and ensuring they’re “good” users / customers.

The focus shifts from building the right product to cracking the go-to-market strategy. You’re still building and iterating on the product, but it should be good enough because it’s solving a core problem you’ve validated. If you reach more users/customers (later adopters) and the product doesn’t create value for them, you need to go back to figuring out problem-solution fit, because you jumped ahead too early. Or you might have to narrow the user / customer segment focus, and avoid broadening into other niches. I love this quote from Rahul Vohra, CEO/co-founder at Superhuman (from Lenny’s Newsletter):

"We found pockets of PMF with specific segments of founders, managers, executives and business development professionals. Once we recognized this, we were able to focus the entire company on serving that narrow segment better than anybody else. It’s a commonly held view that tailoring the product too narrowly to a smaller target market means that growth will hit a ceiling — but I don’t think that’s the case.”

Focusing on go-to-market means experimenting with user/customer acquisition channels.

Your ultimate goal is finding at least one channel that really works, which you can scale and leverage for all it’s worth. You won’t abandon other channels or stop experimenting, but if you can find one channel that’s working well, you should double down on it.

I like what Rommil Santiago said on X, “Dabble to find heat, but focus on just a few.”

Kyle Austin, Founding Partner at BMV said, “You want to be lean in testing a few different channels and see what is moving the needle. From there I think you’re doubling down on what works…”

How do you pick the right channels and tactics?

For starters, there aren’t thousands or even hundreds of options. But you still have to do plenty of homework to figure out the right channels for your startup.

Where are your users/customers hanging out online?

Where are your users/customers hanging out offline?

What sorts / styles of content resonate with your target user/customer? (i.e. short form, long form, video, text, etc.)

What’s your voice?

Answer these questions and figure out the fastest path to engaging customers. You’re looking for the most direct route to interact with customers and point them to what you’ve built. And then experiment.

Note: You can start this work by doing things that don’t scale—but you need to demonstrate there’s a pathway to scale. For example, let’s say you’ve built an app targeted at college/university kids. Going on campus to engage with them makes sense, but it’s not easily scalable. You could recruit ambassadors at each campus, once you’ve figured out a bit of a playbook (so you can give them instructions on what to do), but that’s also not super scalable. Eventually the product will have to do more of the work for you, going viral within a campus and across campuses. But before you build a bunch of features hoping they drive virality, you get on those campuses on your own, with your team, and hustle…hand-to-hand combat style.

Be careful with social channels. They can consume a ton of energy. I’ve seen startups pursuing X/Twitter, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube all at the same time. It gets out of control. Even if you can (and you should!) repurpose content and broadcast automatically, it’s a lot to keep up. Each social channel has its own audience and unique hacks to figuring out growth. These things change over time too. And winning in social takes consistency and patience. You’ll see some brands posting 10+ times per week on certain channels—now that’s commitment!

Keegan Edwards, CEO at New Media Retailer (which helps local businesses attract customers) says, “I’ve always recommended picking two that make sense for your type of local business. Two is feasible to keep up with and do well.” I think this applies to non-local businesses too, especially at the earliest stages of seeking product-market fit.

The tactics you use matter as much as the channels. You can focus on a couple channels, and still do a poor job of it. It’s also important to remember that you do not own your followers / networks on social channels. You have 10,000 X followers? Amazing…but don’t be fooled into thinking you own them.

That’s why I’m bullish on email. It’s a legitimate channel that most startups can use. You own your email list and you can experiment / test fairly easily with it.

I also like leveraging bigger brands. If you can co-market with other brands, some of their reputation (and audience size) rubs off on you. One of Highline Beta’s portfolio companies, SparcPay, does a good job of aligning itself with bigger, well-known brands. They partner with brands such as Intuit and Dext to run webinars. They promote the webinars through LinkedIn (and elsewhere) and make sure the topic is interesting to the target audience. This isn’t about doing a hard sale of SparcPay, instead they’re trying to create content that’s valuable to the target market while aligning with recognizable brands.

In B2B situations, think about how you can leverage your customers to create valuable content. For example, you can host a client in a webinar. Or speak at an event, but alongside a client, perhaps in a fireside chat or panel setup. Put the spotlight on the client. Make them the star. It gives them credibility inside their organization, increases their profile, and rubs off on you.

You can also use users/customers in a B2C context as well. Run a contest that requires they post something on Instagram with a specific hashtag. Give customers a discount if they refer others to your product.

There’s no shortage of tactics, and you should think of each one as an experiment. For each channel you’re leveraging there’ll be dozens of experiments / tactics you may run. Here are some great references to dig in more:

The Ultimate Gide to Marketing Strategies & How to Improve Your Digital Presence - Hubspot

51 Marketing Tactics That Work (And How to Plan Them) - CoSchedule

Marketing Strategy vs. Marketing Tactics

First start with tactics + experiments.

Then build the strategy.

If you build the strategy first, taking a more top-down approach, you’ll spend a long time pontification on what might work in an attempt to craft the perfect plan. Fuck perfect. Go out and do something.

Eventually you will need a strategy, based on what you’ve learned executing a variety of marketing experiments/tactics in several channels. But don’t prematurely try and define the perfect strategy up-front.

What about long form content and SEO?

Blogs are not dead. Neither is long form content. For some businesses, long form content (in blog or other format) makes a lot of sense, especially when trying to establish credibility. AI is making it a lot easier to create content, which is a plus and a negative. The positive is that it’s now easier to create much more content. The negative is that it’s now easier to create much more content. 🤣

If you use AI to create content, double check it. Make sure it’s still in your own voice (which you can actually train AI to do, to some extent.) Use it to generate content that’ll kickstart your SEO efforts.

SEO takes time. It’s not a quick win. But it can result in a growth inflection point. From Lenny’s Newsletter, here’s what Lauryn Isford, Head of Growth at Airtable (now at Notion) said:

“One of the biggest inflection points in growth for Airtable was adding templates. It kicked off the SEO flywheel and ended up accounting for as much as a third of total site traffic at its peak. One of the most interesting elements of this was that templates were seeded with a lot of the content made by creators in the community. This is generally considered the biggest unlock of all time for Airtable’s growth engine.”

You don’t need long form content to drive SEO. At VarageSale we did it with items (we had millions of items for sale on the platform, and we made them publicly available to capture searches).

At Highline Beta we’re experimenting a lot with long form content for SEO, leveraging AI content generation tools, curated by hand. We’re building a toolkit that allows us to “turn on” content capabilities for portfolio companies where we believe it can drive brand building and lead generation through SEO. For new startups it can take months (6-12 easily) for content to have a material impact, but we believe in building the foundation early. We won’t use this as a primary user/customer acquisition channel (it’s not the straightest path to that) but it’s a building block.

What about building a personal brand versus a company brand?

Building a company brand with a unique personality that resonates is very tough. It’s often easier to put the spotlight on the founder(s). The risk is that too much time is spent building the founders’ personal brands and the company doesn’t benefit. Figuring out the balance is tricky.

But it works. I always think back to a video by Midday Squares in 2022 that was awesome. It introduced people to why the founders were building a chocolate snack company with a ton of personality.

They continue to put out amazing content through a couple channels, including Instagram, where they have 127k+ followers. It’s the perfect combination of founder personalities connected to the mission and purpose of their company.

Here’s a similar, but very different example…

Bruce Hodges is CEO at Parachute (a Highline Beta portfolio company). Parachute helps Canadians that are struggling with debt. They consolidate your debt and provide you with tools to better manage your financial wellbeing.

Bruce started Parachute, in part, because of his own experience. When he was 23 years old he was coached into declaring personal bankruptcy. Doing so has huge implications; bankruptcy is a stain on your financial record for a long time. This isn’t an easy story for Bruce to tell. But it’s an important one and it ties directly into the purpose and brand of his company. Here he tells a bit of that story at the Intuit Prosperity Accelerator Demo Day:

One way to build a personal (and by extension, company) brand is through public relations (PR).

PR isn’t an easily scalable channel, but similar to long form content or SEO, it can be a basic building block if you do it right. I wouldn’t invest heavily out of the gate, but getting your name out there for free is compelling.

Take a look at HARO (Help A Reporter Out). They send emails 3x per day from journalists looking to speak with people. The topics range wildly, but there may be some opportunities there. PR gives you a chance to focus on your own brand, establishing domain expertise in a specific area, and by extension make more people aware of your company.

How do you generate more referrals?

Referrals are awesome. They’re one of the least expensive ways to acquire customers. But you can’t just wait for them to happen, you have to engineer it.

For many, that means building virality into the product. This doesn’t always apply, but if you think it does, you should try. Embed a referral program and test the value. What are you giving people in exchange for making referrals?

Here are a few great examples from companies such as Google, Dropbox, Uber and others. And here’s an even more extensive list, with examples from T-Mobile, PayPal, Julep, Morning Brew and more.

Referrals are a strong signal that you’re beyond problem-solution fit and heading towards product-market fit. Even with big rewards for making referrals, people don’t just hit up their entire contact list.

In B2B situations you often have to flat out ask for referrals, even if you don’t have a referral program setup. This can be awkward, but if you have a happy customer, ask.

Meet customers in-person too. Face to face connections are very powerful. Host events in-person (not just online / webinars).

Don’t over think your initial go-to-market approach

Getting to product-market fit can take years. It’s a ton of work that has to start quickly. You don’t have the time or resources to overthink the initial go-to-market strategy. You can easily get overwhelmed with everything you have to do, or could do.

Think about the foundational components you need. For example: long-form content (SEO), PR (founder story).

Do your homework on where your users/customers hang out (online and offline.)

Pick a couple channels and prepare to spend 6+ months building them out.

Get smart about content creation (i.e. reuse stuff, automate through AI, etc.)

Stay consistent.

Leverage your users/customers for content creation & referrals (make them the stars!)

Build referral / viral elements into your product.

Test over and over and over. Rinse and repeat.

Good luck!

Interesting! You are one of just a few people I’ve ever read that include validation of customer acquisition model within the definition of product-market fit. Brian Balfour being the other notable writer I recall.

To me this always seemed the correct definition. After all, if you are not able to profitably reach and influence a market to buy, how can you claim that you “fit” that market? 🤔

Yet strangely almost all other writers and articles define product-market fit as something more akin to what you or I would consider problem-solution fit. Basically that the intended customer likes the product and it solves their need.

This has frustrated me for a decade, but honestly I’ve found it so draining to try and convince the majority of people that their understanding of the pmf term is wrong, that I’ve given up and have moved on to instead finding a different term to express the addition of validated customer acquisition in addition to (problem solution fit as product market fit)