You Don't Have Product-Market Fit (and that's OK)

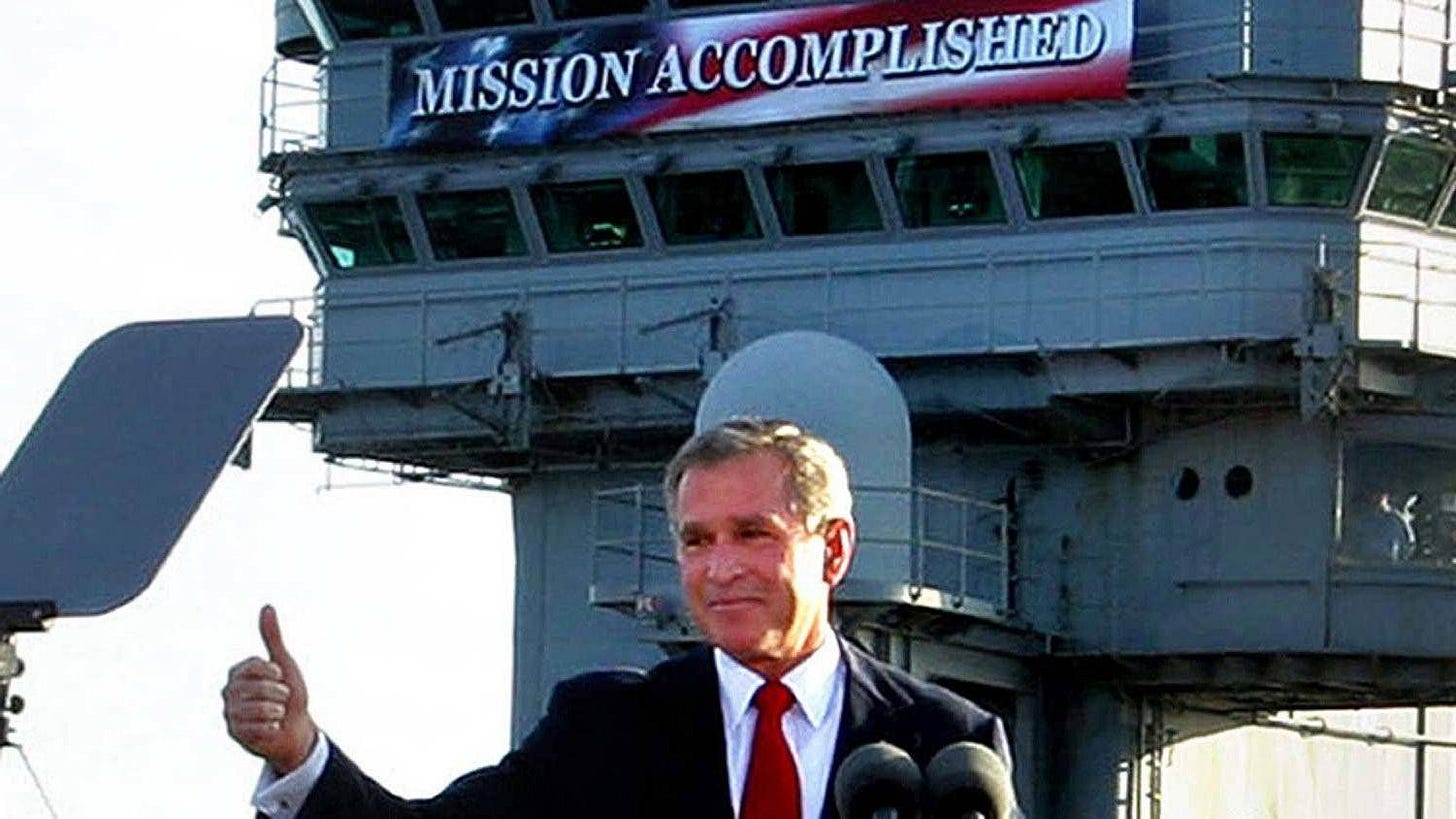

Prematurely declaring Product-Market Fit is running rampant. You can't launch, get 3 users and claim you've won. (#14)

We’ve completely lost sight of what Product-Market Fit (PMF) means.

Perhaps it was never well defined to begin with. But lately, it’s really gotten out of control.

I’ve seen several founders say, “Just launched. Achieved PMF.”

WTF. 🤬

First, how is Product-Market Fit defined?

No one “Googles” anymore, we now use ChatGPT (or Perplexity, which is often more accurate.)

ChatGPT says: Product-market fit is the degree to which a product or service satisfies the needs and desires of a particular market. It means that there is a strong match between the product's features, benefits, and price, and the needs and wants of the target market. When a product has achieved product-market fit, it is more likely to succeed in the market and generate significant revenue.

Perplexity says: Product-market fit is the degree to which a product satisfies a strong market demand.1 It is a process that incorporates a business’ goals for driving sales with the target audience’s engagement and feedback to help the company.2 American entrepreneur and investor Marc Andreessen, who coined the term ‘product-market fit’ in 2007, defines it as “finding a good market with a product”.3 Product/market fit is all about making sure each layer lines up with one another.4

(I don’t know what that fourth point is by Perplexity — layers lining up? The article/reference itself is pretty good though.)

Let’s break this down a bit:

You need a product

You need engagement

You need strong market demand

You need sales / ability to generate significant revenue (this one is a bit fuzzy, do I need this to achieve product-market fit or do I get it after?)

When I asked Perplexity for “examples of product-market fit” it shared this:

I completely agree with Netflix, Google and Slack, but New Coke? Um…?

While it’s true that you can achieve Product-Market Fit and still fail, I’m not sure New Coke ever really got there.

And herein lies the challenge—defining PMF is tough, but since everyone knows they’re supposed to get there, they loosen the criteria to the point where they can declare premature victory.

How I think about Product-Market Fit

Since 2007, when the term PMF was coined, I’ve worked on and invested in many startups. In that time, I’ve consistently raised the bar on my definition of PMF, because I’ve seen how much the term/concept is misused, and how founders assume things get easier. (Hint: they don’t.) The bar for Product-Market Fit should be high—most never make it.

A few thoughts:

Product-Market Fit isn’t a point in time. You don’t achieve PMF and then scale instantly. Getting to PMF isn’t like getting to the top of a mountain (although the local maxima argument would apply nicely here.) While market pull is a strong signal of PMF, this isn’t a Thanos snapping his fingers moment. (For great examples of famous startups achieving PMF, read this.)

You can achieve PMF and still fail. Let’s face it, shit happens. Some of it will be in your control as you scale, some won’t. Often when a startup feels like they’ve hit PMF they raise a lot of capital in an attempt to scale—which usually means adding lots of employees. As a company grows, a lot of things fall off the rails, and so you can have incredible momentum, try and lean into it, and stumble.

Early adopter success is not PMF. When you first launch, you need to attract early users and prove you can create value for them. This is typically a small group (although defining “small” is dependent on the type of product), and you will spend a lot of time working with your early adopters to get things right. But this is not PMF. On their own, early adopters are not a “market.”

The market defines PMF. If the market isn’t generating significant and growing demand for your product, you don’t have PMF. Launching a product isn’t PMF. You need to prove that you can consistently acquire more customers, get them to “pay” (see #5 below) and keep them.

PMF = payment (of some kind.) Not every product needs dollars to exchange hands to hit PMF, but there has to be an exchange of value. Social media apps (i.e. Twitter, FB, etc.) hit PMF because they acquired lots of active users quickly. People were “paying” with attention and data. The actual business model came later. People can pay with actual dollars (yay, money!), attention or data. Those are exchanges of value—I give you a tool you can use to infinitely scroll nonsense pictures of friends and cool brands (Instagram), you give me your eyeballs and tell me what you like (so I can feed you more of it and sell you to advertisers!)

All of this to say, Product-Market Fit comes much later than most founders realize. True PMF for me, means:

You have an engaging product that’s creating value for users (and you can prove that);

Those users are paying in some way (with their money, data or attention); and,

You’re acquiring new users at an increasingly rapid pace through at least 1 channel, and the users you’re acquiring are “good users” (i.e. they fit the criteria for #1 and #2 above.) ← This is important, b/c you can find yourself acquiring “bad users” who don’t get a ton of value and go inactive or churn entirely.

Let’s talk about business models and revenue

I’ve already said that you can hit PMF without having an actual business model that works. Most products that rely on attention and data monetize much later in the process; and many startups don’t achieve profitability for a long time (even post-IPO) including those that charge early in their journey.

The risk here is that you build an engaging product, figure out how to acquire lots of users/customers — achieving PMF — but still fail, because you don’t have a sustainable business.

So PMF is not victory.

Further, if your business relies on consumer engagement to drive a business model where others are paying (i.e. advertisers are customers), then you need to prove a ton of user engagement + acquisition and a willingness for someone to pay. It’s as if you have to hit PMF twice, or achieve PMF for consumers and customers.

Do you need a viable business model to achieve PMF?

Sort of. You need a business model that’s demonstrating signs of working, but again, it’s unlikely you have a truly sustainable (profitable) business before hitting PMF.

Note: Profitability is also not PMF. You could run on a super low cost structure and not be growing the business or achieving tons of quality user engagement. Ramen profitable may be a necessity to survive, but it’s not the same as PMF.

PMF fit at different stages

I love Lenny Rachitsky’s newsletter (I reference it in many posts), but I think he did the PMF discussion a bit of a disservice with his post: How to know if you’ve got product-market fit. (Sorry Lenny!) The post itself is amazing, with tons of great examples that are helpful in understanding how startups made progress through their evolution from pre-product, to product launch, to scale - but each of these steps isn’t Product-Market Fit.

For example:

“You have very strong customer feedback, even from a small group of people. For example, at Color early on, we were getting literal love letters from customers.” - Elad Gil

That is not PMF. It’s awesome, but it’s not PMF.

“I think the right initial metric is ‘do any users love our product so much they spontaneously tell other people to use it?’ - Sam Altman

Sam Altman is probably an actual genius. Infinitely more successful than me. But that’s not PMF. It’s an awesome sign—it feels incredibly good to find out people are recommending your product without you nudging them—but it’s still not Product-Market Fit.

PMF is a moving target. And even if you achieve it, you may not be able to hold onto it, but I don’t believe it can be declared so early in the process. In the examples above there’s no real “market” of any significance. These are awesome signals, but again, not PMF.

How to measure progress across startup stages

Stepping away from the PMF boondoggle for a moment, it is incredibly important that you measure progress throughout the startup journey. Too many startups “skip steps,” especially in a hot market where they can raise a lot of capital and hide the weak foundation they’re built upon.

In Lean Analytics, Alistair and I analyzed many startups’ progression from idea to scale, and came up with a simple framework (the Lean Analytics Stages) that I believe still holds true today. It’s not about achieving PMF at each stage—that’s not possible—but it is about doing things in the right order and recognizing when you should move to the next step.

Here are the 5 stages that we defined:

What we found is that every successful startup (most of the time not really realizing it) goes through these stages. And ideally you don’t skip steps; i.e. you don’t overdo it on user acquisition before you’ve proven your product is sticky and creates enough value; you don’t optimize the unit economics until you know you can grow the user/customer base, etc.

Sadly, a lot of founders/startups skip steps. Common examples:

Many founders love building stuff; they don’t invest enough time in really understanding the user (Empathy), and instead rush to build an MVP.

When VC dollars are flowing, startups can obfuscate engagement, and rely on “growth at all costs.” Ouch.

A few more points about the Lean Analytics stages:

What are the right Stickiness metrics? That depends on the type of business you’re running. Generally I’m looking for proof of engagement, and that the engagement is creating value for users. You can measure engagement quantitatively, but you measure value (especially early on) qualitatively—never stop talking to customers! Examples of stickiness metrics: (1) DAU/WAU/MAU (Daily, Weekly & Monthly Active Users), (2) your own definition of “active user” (which is fine, as long as you’re being realistic & honest about it), (3) churn (although this is typically higher and optimized later, it’s still good to know), (4) activation rate (is anyone even starting to use your product).

What do you mean by Virality? I think we misnamed this, and should have just called it Growth. Virality in the consumer sense is focused on the number of new users brought in through existing users, but in a B2B context, virality is often less clear; and in some cases there’s no real virality at all. But no matter what there should always be growth. At this stage you’re looking to see if you can acquire later adopter customers through at least 1 channel that’s performing reasonably well, and making sure those new customers are engaged. I’m less concerned with the economics (i.e. CAC may still be a bit high) because you can try and optimize that later, but if you haven’t figured out how to acquire good users/customers at a good pace, with some level of consistency, you’re toast.

Why is the Revenue stage so late? It’s because of how we defined it (which is mostly around having a strong business model that is heading towards sustainability and profitability; i.e. the economic engine of the business is working.) You can, and maybe should, charge money earlier; getting people to pull out their credit cards represents strong validation, but prior to the Revenue stage I’d be less focused on optimizing the financial model.

What does Scale mean? Scale means a lot of things, and there are a ton of different tactics that emerge at this point. You might take your point solution and turn it into a platform with a focus on partnerships and building an ecosystem. You might grow the sales team, or expand internationally. You might launch new products/services. At this point, you’ve probably won.

Which leads back to the topic: PMF.

I believe real PMF sits somewhere around or between Virality and Revenue.

Most startups never make it, and actually die in Stickiness (because they don’t build a valuable enough product for a targeted set of users/customers.) But if you can figure out how to grow and acquire users/customers at an accelerating pace, with a lens towards proving a business model and good economic fundamentals, all on a foundation of a sticky product, you have PMF.

Getting to PMF in this model takes time. It doesn’t happen because you built a great product for a small group of users/customers. It doesn’t happen when you execute one growth hack or launch on Product Hunt (no shade on PH, it’s an awesome site!) Real PMF is much further down the pipe—but at each stage you do need the right signals and metrics to prove you’re doing the right things and should move forward.

Premature PMF

Declaring Product-Market Fit prematurely is risky.

You’re feeding into the startup hype machine in an unhealthy way, and I can almost guarantee you that what comes next are a string of bad decisions.

Declaration: “We hit product-market fit! [insert celebratory emojis]”

Next steps (not necessarily in this order):

Let’s raise a lot of money!

Let’s scale!

Let’s hire more people!

Let’s get a fancy office!

Let’s start traveling to every conference!

See what I mean? Bad decisions.

Are investors to blame for prematurely declaring PMF?

Maybe. And that’s scary as hell. They’re doing it to try and juice downstream investment and build hype around their portfolio. I got into a discussion on Twitter with Jean Yang about PMF, and she wrote:

Getting to PMF is hard, but not impossible

My goal isn’t to make you feel like PMF is unachievable. You can get there. But it’s important to be honest: it’s bloody hard and not a ton of startups make it.

Aaron Dinin wrote a blog post recently: Apparently Your Startup’s First 100 Customers Don’t Actually Matter. The title is meant to be provocative, because clearly the first 100 customers (heck, ALL your customers) matter. But he’s making a few important points, including that you can’t declare Product-Market Fit when you hit an arbitrary, magical number of 100 customers.

You can’t really win, at scale, without achieving Product-Market Fit, but if you’re early in your startup journey recognize that it’s a long ways away—and that’s completely OK.

Ani Ganti analyzed how Facebook defines Product-Market Fit, and despite Facebook’s recent challenges with doing anything significant, their approach and definition of PMF is spot on.

First figure out if anyone has a real problem worth solving (Empathy)

Then build something that they use and get actual value from (Stickiness)

Also, figure out who your best users are, and learn everything you can about them

Then figure out how to reach more “good quality” users through scaling channel acquisition (Virality/Growth)

Then make sure the unit economics for the business make sense (even if you’re not at profitability) (Revenue)

Then scale.

PMF is somewhere around Steps #3-#4. Market pull dragging you through the Virality stage is a great sign, but not if you’re burning insane amounts of money. You need CAC (cost of acquisition) to be at least trending in the right direction, and you need proof that how users are paying (w/ money, attention and/or data) gives you a solid foundation for a scalable business model.

#rantover 👊

To inject some humour into this article, I’m sharing this amazing tweet (turn your sound on, it’s even more intense):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Product/market_fit

https://mailchimp.com/resources/product-market-fit

https://www.hotjar.com/product-management-glossary/product-market-fit

https://delighted.com/blog/how-to-measure-and-track-product-market-fit

Thanks for the shoutout Ben! Thanks for calling out all the misused definitions of PMF and the fact that it's not a checkbox that you tick and forget. All founders should read this.

Really well covered. Agree that organic growth / high NPS are not sole determinants of PMF, but it is likely that when PMF is achieved there is a lot of Pull and not just Push.