Product Managers Aren't Growth Bystanders

Alistair Croll and I write a shared post on the biggest issue with product management today: giving up on growth. (#95)

I’ve known Alistair for a long time. We co-founded Year One Labs together in 2010 (with Ray Luk and Ian Rae) and then co-wrote Lean Analytics, which was published in 2013. Since then we’ve spent years debating whether or not to write a 2nd edition. Instead, Alistair went off and co-wrote an awesome book on marketing, Just Evil Enough (smart move!) That spawned further discussions about product, growth marketing and startups. And from there…we decided to co-author this post. Enjoy!

The only reason growth hackers exist is because product managers forgot to do their jobs. 😱

This wasn’t some grand conspiracy. It just happened. Somewhere in the scramble of agile sprints, Jira tickets, and stakeholder check-ins, PMs accidentally handed their most important responsibility: driving the business forward.

Now they’re boxed into delivery roles—owners of roadmaps, managers of backlogs, facilitators of standups. Tactical and essential, sure, but increasingly divorced from the one thing that actually matters: making the business grow.

This goes beyond a missed opportunity. It’s a strategic failure that’s costing companies time, money, and momentum (and if you’re a product manager, really bad for your job security.)

The worst part? Many don’t even realize it’s happened.

It’s time to reset product management.

What does a business actually do?

The boring textbook definition of a for-profit business is that an organization takes in resources and puts out products/services worth more than the cost of those resources. In other words, it’s a value chain, and it creates value for customers (and profit for owners.)

Dry or not, that’s a useful description of what a business does.

To accomplish this task, the business needs to change the behavior of a lucrative target market. Your business asks people (customers) to do something differently in order to use your product, whether you’re creating a new behavior (like Listerine did when it made mouthwashing a daily activity) or changing an existing one (like Scope did when it convinced people to switch from Listerine.)

All successful marketing produces behavioral change.

That behavioral change doesn’t happen by magic. It’s written down in a business plan that clearly explains how value will be created. The plan’s go-to-market strategy describes how you’ll change the customers’ behavior—from capturing their attention, to distributing your offering, to handling things like support, referrals, and discounts.

A business plan explains how you’ll generate profit by delivering value. But it’s hardly the only way to make a profit. In order to understand the role of product managers better, let’s look at two extremes of profit-making: Casinos and Treasury Bills.

The spectrum of ROI and certainty

Walk into a casino, head to the roulette table and put all your money on red 14. Go ahead, we’ll wait.

Casinos are a high-risk, high-return investment. You have 100% certainty of a great return, but very low odds of achieving it.

If you’re a more conservative investor, you might put your money into government bonds or treasury bills. They’re a very low-risk, low-return investment. But again, one with a very high certainty of that return.

Casinos and treasury bills are at either end of a spectrum of potential investments you can make. Businesses exist somewhere in the middle. Investing in a business is a bet that you’ve found a better risk-to-reward trade-off than casinos and treasury bills.

The price for that is certainty.

Here’s an illustration of risk/return/certainty:

Your business plan is a bet that you can be above the line, and that your venture will deliver a better average return than both the casino and the treasury bill. Otherwise, investors would spend more time studying casinos and bond markets.

This means to win, every part of the organization has to be constantly optimizing the tradeoff of risk and reward. That’s why in Lean Analytics we recommend identifying the riskiest part of the business first, de-risking it, and iterating.

Where do product managers fit into this?

Okay, back to product managers abdicating growth.

A product manager’s job is to define and deliver a product roadmap (as part of the business plan) that identifies the biggest risk, mitigates it and repeats.

But what’s the biggest risk?

Most startup founders (and team members) will say: “The biggest risk is proving that someone will care, not if we can build it.”

Unfortunately, if you ask product managers what they spend most of their time doing, they’ll tell you it’s almost entirely devoted to building things, rather than whether anyone will notice or care. That’s not a huge surprise: you work on what you can control, and product managers control the roadmap.

But it’s not what’s right for the business.

(Side note: We’re not saying that product managers don’t do user/customer validation to figure out if people care—most do—but it’s isolated and contained, not focused on how to make people care or scale reach.)

If growth, reach, and behavioral change are the biggest risk (“will anyone care?”) and product managers are in the business of mitigating risk, what’s their job in this context?

Growth.

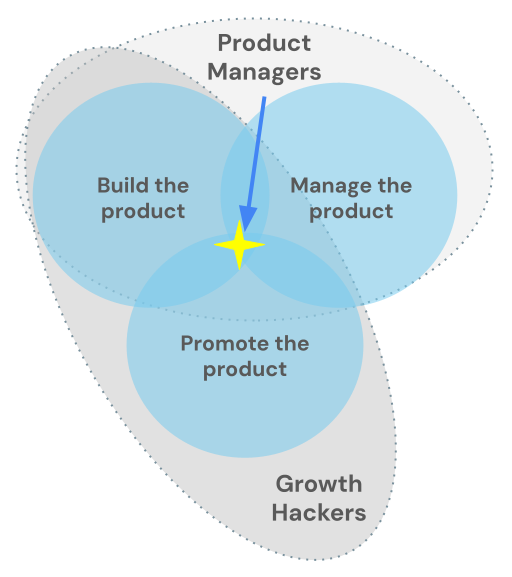

The Growth Hacker role emerged because product managers stopped paying attention.

The biggest risk doesn’t live in the product, it lives in your ability to grow.

An average, by-the-book product manager diligently maintains an ordered list of features to build based on customers’ expressed wants and needs.

A good product manager knows that sometimes customers don’t know what they want, and figures out what’s seldom requested but actually needed.

The best product manager knows what one thing to build based on their business model (i.e. how to grow), not just the features customers might want.

Seen through that lens, the product roadmap isn’t what customers want, it’s what the business needs. That includes go-to-market strategy, price tiering, product-led growth/upselling, leveraging data exhaust, operational simplicity and more.

Product managers brought the Growth Hacker schism on themselves, when they focused on tickets and talking to customers while abdicating growth to the marketing communications department. As marketing became more technical and integrated into the product, companies filled that void because they needed growth.

This doomed product managers to the drudgery of wireframe reviews, Jira tickets and documenting user personas.

Brian Chesky was right, but he didn’t eliminate product managers

Many product managers abdicated their marketing responsibilities, forgetting that they’re part of a system that is executing a business plan.

Remember when Airbnb made headlines for “getting rid of PMs”? That was never the full story. What really happened was more radical: Airbnb expected PMs to also act as product marketers.

They were told to own the story, the emotion, and the growth. If a product didn’t change behavior in the market, it wasn’t done yet.

That’s not a takedown of PMs. It’s a call for bigger ownership.

Who actually owns the product roadmap?

The easy answer: product managers.

But is that really the case?

If growth is the biggest risk, and Growth Hackers own that function, shouldn’t they be in charge of the product roadmap?

As a result of this “shift in power” Growth Hackers are dominating the product roadmap, particularly in tech products that rely on product-led growth for upselling and revenue. Product managers were relegated to project managers, preoccupied with task management and getting things built on time—but never questioning whether they were the things the business model needed built.

Meanwhile, companies end up with competing product roadmaps, leading to infighting and inconsistent plans. After all, the problem with two people owning the roadmap is that you don’t have one throat to choke. There’s no person with ultimate responsibility and accountability.

Wait, What About Product-Led Growth?

The rise of product-led growth (PLG) has exacerbated the confusion and challenge for product managers. On the one hand the word “product” is right there in the description, which is a good thing. On the other hand, many product managers—having been confined to coordination roles—are ill-equipped to drive PLG successfully and reclaim their mandate.

Where does PLG end and marketing begin? Is changing the copy of a button on the website within a product person’s purview? What about experimenting with pricing tiers (on the website) or upselling options (in the product)?

We get it. This stuff lives within a fuzzy territory, with increased overlap between sales, marketing communications and product. We don’t think that’s a bad thing, we think it’s the job of product managers.

PLG is a powerful model—but it’s often misunderstood. While it promises that the product itself drives acquisition, activation, and retention, what’s actually happened in many teams is this:

PMs talk about PLG but still measure success by features shipped—not behavior changed.

Growth gets assigned to a siloed “growth team,” distancing core PMs from the metrics that matter.

PMs adopt the language of PLG without the discipline of driving outcomes.

PLG doesn’t reduce the need for PMs to focus on growth. It raises the bar. If your product is the growth engine, your PMs better know how to drive.

PLG isn’t the solution to this problem—it’s the context that makes the problem more urgent to solve.

Product managers: Get with the program and read everything Kyle Poyar writes at Growth Unhinged. He’s talking to you.

So stop listening to users?

Of course not.

Getting out of the building and engaging with users is essential. But “listen to your users” has become a sacred commandment that people follow blindly. Just as we said “don’t be data-driven, be data-informed,” a product manager must be informed by users—but letting those users own the roadmap is a trap.

Too many PMs have become glorified customer service reps with a Jira login. They collect feedback, nod politely, and feed it straight into the backlog like it’s gospel.

But here’s the truth: listening blindly to users won’t save your product.

In fact, it might kill it.

Customers can tell you what’s broken, but they can’t see around corners. They’ll ask for things that seem familiar, not things that actually solve the deeper problem. It’s your job to spot the difference.

If your roadmap is just a list of complaints with shipping dates, you don’t have a product strategy—you have a support queue with a nicer interface.

Example: When Intercom first launched, they got flooded with requests to add more help desk features—ticketing systems, SLAs, the works. It made sense on the surface. But if they had caved, they would’ve become just another Zendesk clone.

Instead, they stayed focused on what made them different: lightweight, real-time messaging designed to feel personal. They did evolve their offering—but not by blindly following every feature request. They zoomed out, asked “what’s the underlying job to be done?” and doubled down on their thesis: human conversations at scale.

That’s product leadership. Not product reaction.

So yes, listen to your users. But don’t let them write your roadmap.

Treating PMs like Jira admins kills companies

This issue isn’t just for startups. It exists across organizations of all sizes. And it’s not specific to Jira either (although we mention it a few times!) 😂

When the product roadmap is split into product managers (beholden to users at the expense of growth) and growth hackers (who optimize tactical improvements, but don’t have strategic vision for what the product can become), here’s what happens:

Lack of accountability: Nobody has final say on the roadmap.

Reactive decision-making: PMs optimize for output, not impact.

Organizational confusion: The product manager and the growth hacker both live between engineering and marketing.

Siloed strategies: Features are shipped that never move key business metrics.

Product manager job security: If PMs are simply Jira Prioritization Engines, they’ll soon be replaced by AI.

Product-led growth, both pre-sales (Dropbox’s shared storage invite model) and post-sales (upselling storage capacity once a power user reaches a limit) clearly focuses on functionality—but not functionality the customer asked for. Unless growth and functionality are blended into a single roadmap, you get mutant roadmaps nobody wants.

The Product Roadmap is a Growth Tool

As Alistair outlines in Just Evil Enough, your roadmap isn’t just a list of customer requests or engineering deliverables. It’s a strategic weapon.

“Your roadmap isn’t what customers want. It’s what the business model needs.” — Just Evil Enough

The best PMs don’t just ask what to build—they ask:

What behavior are we trying to create or change?

What’s the riskiest part of our business model?

What’s the one thing we can test to mitigate that risk?

That includes pricing. Messaging. Channel. Virality. Conversion. Referral loops. These are product problems. Or they should be.

Buy Just Evil Enough!

In 2012, Alistair and I published a book that showed generations of startup founders how to use data to build a better business faster. For the better part of a decade, Alistair and his co-author Emily Ross have been studying how the best organizations subvert systems. To succeed, a business has to get the system to behave in a way its creators didn’t intend—and this is a skill you can learn.

Just Evil Enough includes over 160 case studies, a new tool to scan your environment called the Recon Canvas, 11 subversive tactics that appear time and again across history, and new frameworks like the Long Funnel and Value Chain Disruption. It’s available on all major platforms. You can grab a first edition hardcover direct from the authors while copies remain by visiting justevilenough.com.

How to Reclaim Growth as a PM

1. Hunt for the Riskiest Assumptions

Chances are the riskiest assumption is related to whether or not anyone will care and your ability to reach those that do. Start hunting for feature gaps in your go-to-market. Why would anyone talk about what you do? How do you make something about your product or service so compelling people feel stupid for not having adopted it already? What new feature completely reframes how your target market thinks about value delivery? Can you reorder, merge, split, or reassign a step in value creation in a way that puts competitors on their heels?

For a structured way to identify, prioritize and test assumptions, read below:

2. Think Like a Zero-Day Marketer

Just Evil Enough is full of examples where products win not because of feature superiority, but because of go-to-market ingenuity. Think:

Uber paying black car limo drivers to idle, creating supply ahead of demand when they launched.

Burger King launching a $0.01 Whopper promo—only redeemable from a McDonald’s parking lot, forcing people to not only download their mobile app, but also turn on location services and enter payment information.

Gmail crushing competitors with 100x more storage—and using a fake scarcity model, as Github did, to make access to their tool seem more valuable.

Energage running Best Workplaces surveys with regional newspapers that they could bait-and-switch into B2B sales of HR software.

These, and 156 other case studies, are included in Just Evil Enough. You should probably buy a copy.

None of these was a feature the customer requested. All of them required software development, and therefore had a place on the product roadmap. All of them were instrumental to the successful growth of the company.

Product features can be growth levers—PMs just need to start pulling them.

We love this line from Leah Tharin’spresentation at MTPCon 2025, “Product managers are always building good products, but forget to build successful products.” Yup, that’s it.

3. Don’t Be Afraid to Be Weird

The best growth strategies often feel strange, even uncomfortable. That’s why they work. The comfort zone is where competitors live. When Coca-Cola invented the coupon, economists and lawmakers criticized it as illegal currency that would complicate inheritance law. When the Blair Witch Project launched, it told the press its actors were missing or dead. It went on to become one of the most profitable movies in history.

In an attention economy, where traditional content marketing just adds more noise to the cacophony of the market, novelty stands out. Stop worrying if your tactics are too unconventional—you’re probably not being weird enough.

Disagreeability is an essential element of subversive thinking. Worry less about what others think. But this is not an excuse to let the end justify the means—Alistair and Emily devote an entire chapter to not actually being evil. 😮💨

4. Track What Actually Matters

Product managers need to connect the work they’re doing—experimentation, new feature releases, etc.—to a business metric that actually matters. It’s important to understand how the One Metric That Matters (OMTM) and the North Star Metric (NSM) work together. You should have a OMTM per experiment or feature or new release to verify that whatever you’re doing is creating value at a granular level. But if that doesn’t bubble up to a business metric (the NSM) and move that needle, you might be wasting your time.

Ultimately, Play the Right Game

“Bad founders try to play the game right. Great ones play the right game.” — Just Evil Enough

Product managers are overdue for a similar leap. If your job is just shipping what stakeholders ask for, you’re playing the wrong game. Reclaim growth. Drive behavior change. Make people care. That’s how products win.

Your roadmap, product and business depends on it.