When to Recruit Founders into Your Venture Studio

This is one of the most important decisions when building a venture studio. (#60)

Q: I’m building a new venture studio and trying to figure out the right time to bring in founders. Any thoughts?

I’m happy that people are starting to send me questions. Please keep doing so! It helps me figure out what matters and where to take this newsletter.

It’s a great question, because it’s a key variable for any studio. There’s no “right answer” but your decision will have a huge impact on what kind of venture studio you run, how you support founders, equity deal structures and more.

For starters, take a look at the checklist I created, which includes 60+ variables/questions for designing a venture studio. There are several that are related to founders, including when you recruit them.

For simplicity’s sake, I’m going to define 3 key moments when you can recruit founders:

At the very beginning: Before you’ve done any real validation work on an opportunity.

In the middle: You’ve done some validation work, but it’s still early, and a lot more needs to be figured out.

At the end: You’ve done a lot of validation, and you may have already built the MVP and secured traction.

Recruiting Founders at the Beginning

Most venture studios aren’t recruiting at the very beginning. In a way, this is the highest risk time to recruit a founder because little has been done to validate the startup opportunity.

There are three ways this can work:

1. Your studio recruits founders with their own ideas

Founders should have already done work on the idea, with a focus on validating the problem through research and customer discovery. If someone comes to you and pitches a random idea with zero work done, walk away. If they’ve done a bunch of work already, and you can vet the work (i.e. review the interviews, dig into the research, etc.) you may decide to move forward.

2. Your studio has a very vertical focus and attracts founders specifically interested in that vertical

With a narrow vertical focus, you may find strong founder-market fit at the very beginning, even if no work has been done to validate the startup opportunity.

In this case, you may find founders who haven’t previously done any of their own validation, but know the space and care about it deeply—they’re domain or industry experts and want to build a relevant company, they simply don’t have their own idea.

3. You’re running more of an accelerator / cohort-based volume approach

Some venture studios are playing a volume game, more akin to what you’d see with an accelerator. This is where definitions get fuzzy. If you’re taking this approach (i.e. imagine bringing in 5-10 founders at once) you can do so at the very beginning and weed them out before deciding which ones to back. VCs that are running studios seem to be taking this approach (or a variation of it).

Note: The three options above aren’t mutually exclusive.

What’s the ideal founder profile to recruit at the beginning?

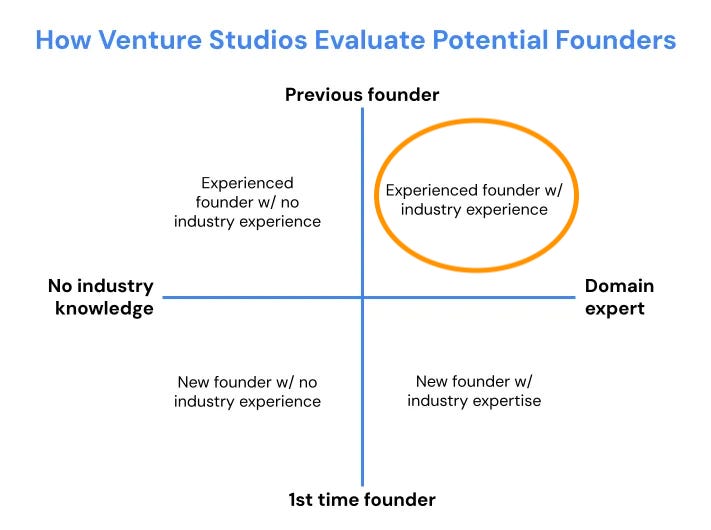

I wrote a post that digs into founder profiles more deeply: The Ideal Founder Profile for Venture Studios. In it, I visualized four quadrants for founders based on industry and startup experience.

If you’re recruiting founders at the very beginning, I’d focus on the top-right quadrant. You most likely need an experienced founder with industry experience. You might consider an experienced founder with no industry experience, but the learning curve could be steep. Similarly if you go with a new founder with industry experience, they may find building a startup from scratch incredibly difficult.

Key considerations for recruiting founders at the beginning

Here are a few things to consider if you choose to recruit founders very early:

Bring them on as contractors: I don’t know of any venture studios that incorporate right at the outset (although some might!), which means founders aren’t becoming CEOs immediately and aren’t receiving equity. Instead, date them first to see how it goes. Give them a modest stipend and set a time limit (3-6 months) to see how far they get.

Give them more equity: If they’re there from the very beginning, expect the founders to want more equity. The studio hasn’t de-risked anything or created any value yet, and the burden of validation will fall more on the founders’ shoulders. In that situation, they deserve more equity. It would be strange to recruit a founder at the outset, expect them to lead everything, and then have the studio take most of the equity.

Founders should invest: If they’re brought on as a contractor to explore an opportunity, they haven’t put real skin in the game (except for their time). Founders that join studios super early, especially if they’re bringing their own idea, should be prepared to invest their own capital and not expect the studio to foot the full bill (even more so if the founder is getting most of the equity).

Founder-led: The earlier you recruit a founder, the more expectations on their shoulders. Your venture studio still has to provide a lot of support and value in building + funding the startup, but the “power dynamic” shifts, especially if the founder has an idea at the outset.

Recruiting Founders in the Middle

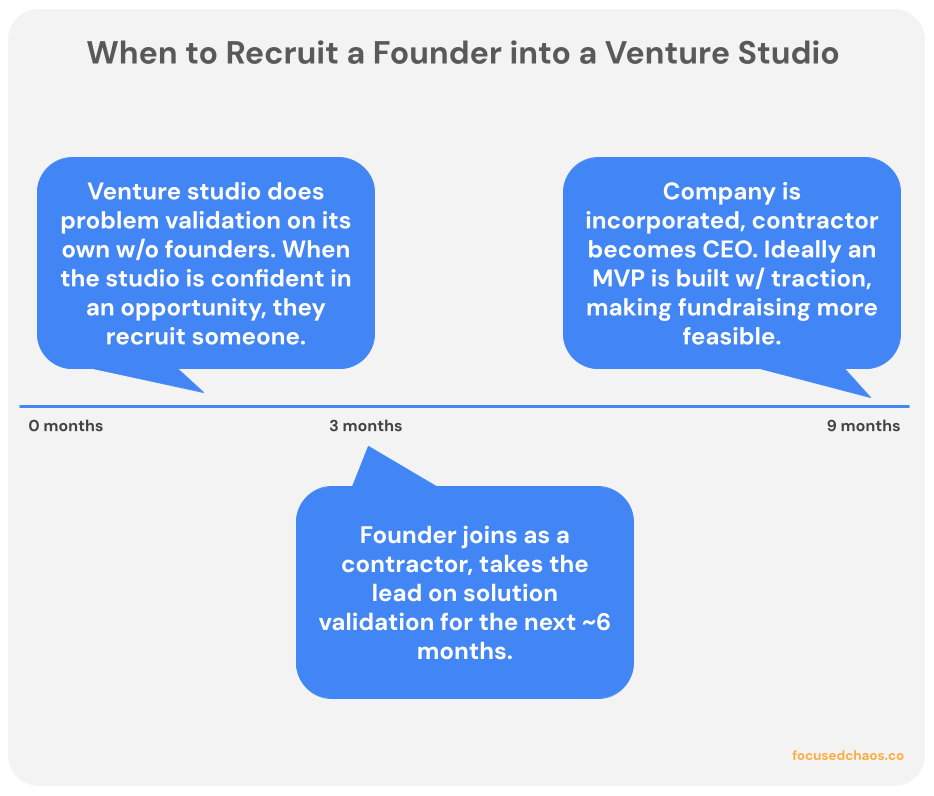

What exactly does “in the middle” mean? It’s up to you, but in my experience, the right time to recruit a founder at this stage is when the problem validation work is complete.

For clarity, I define this as having identified and validated a painful enough problem, faced by a reachable group of people, who will “pay” to have it solved.

“reachable group of people” = a defined ICP (ideal client profile) that you’re confident you can acquire (because you know how to get to them)

“pay for” = buying the solution with money (yay!) or exchanging their attention or data for the solution (often the business model for B2C companies)

You can dig in on how I define problem validation here: How Do You Know You’re Solving a Problem That Matters?

Most venture studios do some amount of problem validation on their own, which includes:

Secondary research (i.e. researching a market through secondary sources; Google/Perplexity, market reports, competitive landscape, etc.)

Primary research (i.e. interviewing potential users/customers); understanding the pain points, hacks they’re using to solve the problem, etc.

Testing concepts / prototypes (i.e. building things, often low-code/no-code, landing pages, physical stimuli) to hone in on the problem and start to understand the solution

To learn more, read: Test First, Build Later: A Guide to Validation Your Ideas With Stimulus & Prototypes

If you look at this through the lens of Design Thinking’s model of Desirability, Viability & Feasibility (DVF), you’re trying to validate the following:

Desirability: Through customer discovery/development & research, can you prove people have a really painful problem that they need solved? (Note: This is validating a proxy of desirability, because you haven’t built the solution and put it into customers’ hands.)

Viability: You’ve done enough market analysis and business model testing to know that you can acquire early adopters and prove the business model. (Again, this is a proxy test, because you haven’t launched, so you’re doing all of this through research, experimentation & spreadsheets.)

Feasibility: You have a sense of the solution that’s needed, and have assessed the technical feasibility of building it. You’ve also evaluated, if necessary, any regulatory, compliance or legal issues. (Remember: You haven’t built anything yet, you’re simply trying to answer the question, “Can we build the MVP?”)

All of this is problem validation. You’re confident the problem is real and painful, you know who has it and how to reach them, and you have a good sense of what the solution and business model should be. You’ve also identified any major risks, with ideas on how to mitigate them.

This is an interesting time to recruit a founder. Directionally you know where you need to go, and you can start shifting into execution—it’s time to build the MVP and bring something to market ASAP. But it’s still early; there are plenty of unknowns and tons left to learn. A founder is coming in with your plan of attack, but things won’t go perfectly and the founder will need to be adept at leading and pivoting.

What’s the ideal founder profile to recruit in the middle?

I like experienced founders without industry experience, because they’re not “tainted by” the industry. An industry veteran may be set in their ways, or disenchanted with how the whole industry works, convinced there’s no way to make a difference.

Starting in the middle means you’ve built up experience and know-how with the opportunity you’re pursuing, and if you are a vertical venture studio (which I recommend!) you can bring in great founders without industry experience and get them up to speed quickly.

Founders with no industry experience still have to be passionate about the opportunity, they’re not coming in as operators that can execute a proven plan with a dedicated team. You don’t have a solution in-market with existing customers. The founder still has an insane amount of work to do, and if they’re not committed to the industry / space / opportunity area, they’ll likely bail.

New founders with industry experience may be a good fit, but they’ll need a lot of handholding. At least the initial validation is complete; most new founders won’t have experience with that type of work, but they may be familiar with what’s necessary to build a solution and take it to market.

Key considerations for recruiting founders in the middle

Here are a few things to consider if you choose to recruit founders in the middle:

You may incorporate right away when the founder joins. This is a key part of designing your venture studio—when do you incorporate new startups? You can do it at this stage and the founder becomes CEO, or you can hire them as a contractor and date for awhile. If you bring them in as CEO immediately, there’s a bit more risk if things don’t work out. But if you bring them in as a contractor, you may find there’s less commitment at a critical execution phase where your goal is to build the product, get to market and “graduate” the startup as quickly as possible from the studio.

Founders still deserve a lot of equity. You’re only a few months in and while your studio has done meaningful work, you can’t pretend the plan you have is a perfect one. You’ve invested ~3-6 months into something, which is valuable, but the founder will spend the next 3-10 years of their life on this one opportunity.

Be super clear about what you provide going forward. This is true if founders join at the beginning as well. Given that there’s so much more to validate before the startup has a chance of scaling, you need to be crystal clear on what services and value you provide and your expectations for the founder. If you bring founders in at this stage, the work is primarily founder-led (i.e. the founder drives most/all of the decision making), but your studio still has to do a lot. If the services / value you’re providing are murky it’ll create a lot of uncertainty and “desert wandering” which isn’t good.

Recruiting a Founder at the End

Some studios only recruit founders near the end of the process, when they’ve validated the solution and secured initial customer traction. They might have already built the MVP, or they’ve built prototypes that customers have seen. The studio already has customers signed up and/or paying, or the studio has secured letters of intent (LOIs) from customers that have agreed to purchase the product once it’s built.

If you take this approach, assume you have to spend 6-9+ months on each venture before incorporating and bringing in a founder. That’s a lot. It means you’ve identified the opportunity area, validated the problem and the solution (either in proxy through a prototype or for real as an MVP). You should have a plan of attack for how to go-to-market and acquire more customers (still early adopters) with the confidence that the solution will create value.

Using the DVF model again:

Desirability: You’ve proven it, and not just through customer interviews. You’ve built the solution and customers are using it, or you’ve built a prototype and customers have agreed to pay for it (paying for something is a strong signal of desire).

Viability: You haven’t proven viability at scale (i.e. you don’t know if the business will be profitable), but you have validated a willingness to pay. You have a lot of confidence in the business model and go-to-market strategy (because you’ve proven both, at least to an extent).

Feasibility: You’ve proven feasibility (if you built the MVP and launched it) or you’re extremely confident in feasibility because you’ve mapped out the scope of the MVP (features + technical infrastructure). You’ve had enough time to review any regulatory, compliance or legal risks and you’re OK with them (or they’re not relevant).

What’s the ideal founder profile to recruit in the middle?

I would focus on experienced founders with no industry experience. It’ll be a bigger candidate pool than experienced founders w/ industry experience, and you’ve ostensibly de-risked a lot.

Founders have to be passionate about the space and willing to get up to speed quickly, but it’s even easier to do that at this stage versus starting in the middle, because you know and have a lot more.

New founders with industry expertise are also a good fit—they know the space (and hopefully aren’t burnt by that). They don’t have founder experience but a lot of the messiest parts of building a company are behind you. I wouldn’t dismiss how much work is ahead, but an inexperienced founder with enough assets to leverage can figure things out.

Key considerations for recruiting founders at the end

Here are a few things to consider if you choose to recruit founders at the end:

Founders become operators. To be clear, the startup you’re recruiting for is still extremely early stage, but a decent amount has been validated. You may widen your search to folks that are more operators than true, super-hustling founders. Be careful! There is a difference between an operator and a founder and you absolutely need founders, but the studios that work this way tend to bring in people with more operational, generalized experience and focus less on the “founder mentality” or “founder grittiness.”

Founders get less equity. Studios that operate this way often take a much bigger chunk of equity, because they’ve invested more in the venture. This can range from 25-50%+ (I know, it’s a wide range!) before the studio invests capital in the startup. That’s why studios in this situation often own 40-75% of a startup, covering the sunk cost they’ve already put in and any capital they invest as well.

You can learn more about how different venture studios operate here: The Many Flavors of Venture Studios

Chargebacks are common. Some venture studios invest capital and then require the startup to pay them for their services. This is more common for venture studios that recruit founders later, because up until that point everything is a cost for the studio. So the studio has invested a lot of time + money, and they’re looking for cost recovery. Note: The chargeback strategy won’t be exclusive to studios that recruit founders later. In the end, your venture studio has to pay its bills somehow. There are a few ways you can do it, and one of them is through chargebacks (although I’m not a fan).

I’ve written about venture studio business models before: Understanding Venture Studio Math

It should be easier to raise capital at this stage. Most investors are not investing at the super early stage, when a company is just an idea. Incorporating later, with more work done (i.e. problem validated, MVP built, early traction secured) increases the odds that you can find co-investors, which is good, because you may not want to foot the bill for the next stage (i.e. pre-seed to seed). In some cases, studios are leaping to a seed round at this point (say ~$2-$4M+ in funding) because of how much work they’ve put in. One caveat: Many investors will struggle with cap tables at this stage if the studio owns too much. There’s more traction, the deal is de-risked, but the cap table is A-typical (compared to a standard startup-VC deal).

My Recommended Approach

There’s no perfect way of doing this and each studio will approach founder recruitment a bit differently. At Highline Beta we’ve recruited founders at each stage and learned a lot. But breaking it all down, I think the best approach is to recruit founders at the middle stage—not too early, not too late.

Recruiting founders at the very beginning creates a serious level of commitment early on, even if you hire them as contractors. Breaking up with founders isn’t easy. You have to sort out who owns the work that was done and responsibilities going forward. The founder may have brought their own idea, in which case there’s a real risk that they’re in love with it and not willing to go through a thorough validation effort.

Recruiting founders at the end gives the impression that a lot has been validated and locked in, when in fact that’s probably not the case. Startups created this way will still succeed or fail because of the founder (+ their team), regardless of the work you’ve already done. I’d bet many of these startups will pivot (b/c many startups do!) So is it worth putting 6-9+ months of work in before bringing in a founder? You’ll definitely get a lot more equity, but most of the startup’s future is still to be written.

Recruiting founders in the middle provides the right balance between the studio’s effort and the founder’s effort. The studio has done the problem validation and has conviction around the opportunity, but brings the founder in to lead the solution validation process. The founder is given assets and leverage, but doesn’t feel like they’re a “hired gun”—it’s clear they run the company and can drive it where they see fit.

I would consider bringing them in as contractors first, until solution validation is complete. This is a good dating period for everyone, but ownership over the “IP” is clearer, because you’ve already put work into things. Founders aren’t coming in with their own ideas at this stage, so they feel less ownership (which is good in this context), and things are less messy. You get through solution validation and then incorporate; the founder gets the bulk of the equity, so the cap table isn’t unreasonable, and you have a good chance of raising right away (“We’re only a few days into being incorporated and we already have traction!”)

Your studio has to be capable of funding the whole process until the company incorporates, so you have to consider that in your model. Studios that incorporate earlier can raise funding for their startups earlier (despite the difficulty of doing so), which helps offset the cost. But I still think recruiting founders in the middle is the best approach, balancing the risk and reward for everyone.

Ben, thanks for the great rationale on founder hire timing; this is really helpful as we explore alternative models for how we build and hire.

Great article as always! Super, Ben!