Understanding Venture Studio Math

How do venture studios build sustainable business models? (#46)

The momentum around venture studios continues. But how do they really work?

There’s no simple answer. Each venture studio operates differently. There are consistent fundamentals that remain (largely) the same:

Venture studios provide more services to founders / startups (compared to VCs or accelerators) which takes considerable resources (namely people). The services vary, but may include:

Doing initial validation on an opportunity area

Helping build the MVP and taking it to market

Recruiting (for the startup’s team)

Business development (especially connecting startups to corporate partners)

Fundraising support

Administration (i.e. accounting, bookkeeping, company setup, HR, etc.)

Venture studios take a bigger equity stake than early stage investors or accelerators, ranging between 15-80%. That’s a big range, and how they take the equity varies. Some might take common/founder shares upfront (in exchange for the “sweat” they put in) and then invest capital for preferred shares. Others might do it all as common, or all as preferred. Deal structures vary.

More Equity Early Means Bigger Potential Returns

This is pretty basic, but the more equity a venture studio owns in a startup (especially at a low valuation) the higher likelihood of a return, including a big one. This is true for all early stage investors, as was made clear in two recent cases: (1) Instacart going public; and (2) Loom being acquired by Atlassian. I don’t know how much equity each investor owned, but the ones that got in early won, and the ones that got in late did not.

Instacart Investor Returns

Here’s a table showing investor returns when Instacart went public. In this case the early stage investors did well, the later stage ones did not. Sequoia made money investing at Series A, but lost badly at Series I.

Here is an awesome analysis of the Instacart IPO (and the company itself) by Aswath Damodaran. Definitely worth reading. He has a conclusion statement in the post that I had to share:

The notion that there is smart money, i.e., that there is an investor group that is somehow wiser, more informed and less likely to act emotionally than the rest of us, and that it earns higher returns than the rest of us, is deeply held. In my view, it is a mirage, since every group that is anointed as smart money ultimately ends up looking average (in terms of behavior and returns), when all is said and done. It happened to mutual fund managers decades ago, and it has happened to hedge funds and private equity over the last two decades. For those who are holding on to the belief that venture capitalists are the last bastion of smart money, it is time to let go. While there are a few exceptions, venture capitalists for the most part are traders on steroids, riding the momentum train, and being ridden over by it, when it turns.

Ouch. 😅

Loom Investor Returns

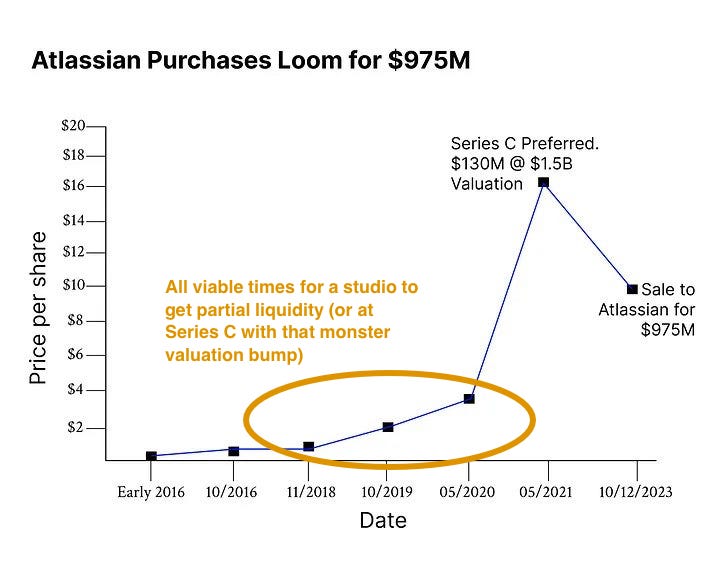

Loom recently exited to Atlassian for $975M. Here’s a summary of the investor returns:

Phil did a further deep dive on the results. Imagine making $40M on a $622k investment. Damn. 💰 💰 🎉

Entry Points Matter

I learned this lesson as an angel investor.

The lower the valuation when you invest, the better. It increases the likelihood of a positive outcome. And there’s no earlier time to invest than at incorporation, which is why venture studios get in at the earliest stage possible.

Getting in early gives you optionality on how and when to get out. Although you don’t have true control over this (you can’t force investors to buy out your equity), a lot of venture studios push for secondaries once a company gets to Series A+. It’s usually around that time that downstream investors are particularly twitchy about how the cap table is structured and everyone wants to make sure the CEO (and other key team members) are properly incentivized to keep going.

Venture studios will often look to exit a portion of their position as valuations climb and let the rest ride, driving early returns back to their investors, but keeping some in case the company really pops. Some venture studios (depending on how they’re structured) can recycle the cash to make other investments or cover operational costs, which supports (but doesn’t ensure or guarantee) a sustainable business model—you’re hoping for early liquidity to help pay the bills going forward.

Early entry points at low valuations also mitigate market timing risk. Instacart went public at a time when the IPO market was very quiet. And they’re down significantly from the IPO price, wiping out a lot of earnings. Loom sold in a down market too, and sold at less than their previous valuation. In both cases the early investors still did extremely well because of the early entry points. If the market was frothy, they’d have done better, but perhaps neither company would have exited either (they would have kept raising capital and staying private).

Let’s do some basic back of the napkin math using Loom as an example. Imagine that Loom came out of a venture studio that had 20% equity at the very beginning (I’ve assumed the company was worth $5M at that time). When Loom raised its $10.7M Series A it did so at a ~$40M valuation (according to CB Insights). There was also two Seed rounds totalling ~$4M beforehand, and I’m assuming that the venture studio didn’t follow on.

After the Seed rounds, the venture studio’s equity is diluted to ~15%.

Going into the Series A, the venture studio is able to sell 50% of its shares at the $40M pre-money valuation, which equals $3M.

If you assume the venture studio invested $500k then they’ve already generated a 5x return and still hold 7.5% equity (which subsequently gets diluted further). Even if the studio invested $1M, they’re still at a 3x which isn’t bad at this stage.

After Loom goes through more funding rounds and dilution continues, the studio ends up with somewhere in the range of 3-4% (it’s difficult to calculate precisely). At exit this translates to ~$30-40M, which is a huge multiple on the original investment. (I recognize this is very basic, and doesn’t take into account all the investment terms that may exist.)

It’s clear that getting in early makes a big difference when there’s a significant win. If the exit isn’t as substantial, the earliest investors often get crammed down, or liquidation preferences take over (especially in the current funding market where you’re seeing 2x+ liquidation preferences), which is why venture studios are open to getting out earlier. They’re OK with not rolling the dice on the big win if they can generate faster returns (on a consistent basis).

Should Venture Studios Follow On?

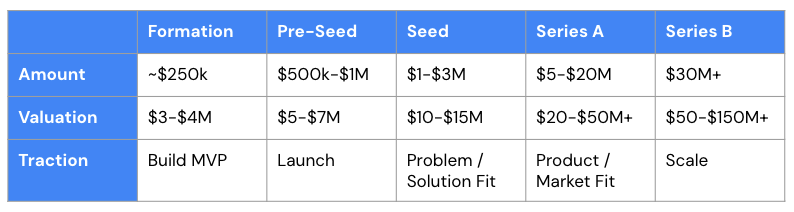

Most venture studios aren’t built for follow on investing because they don’t have the capital to do so (what’s called “Assets Under Management” or “AUM”). They may invest in 1 or 2 early stage rounds after incorporation, but beyond that it’s tough. Defining and naming financing rounds alone is tough, but generally this is how we see it at Highline Beta:

Take the numbers above with a hefty grain of salt. There are so many variables involved that it’s incredibly difficult to define these stages, financing needs and valuations accurately. But for the purpose of this discussion, assume most venture studios are investing up to, but not including, the Series A. Some may not invest beyond the formation stage.

Each venture studio has to make its own decisions as to whether it follows on or not. This depends on whether they have the capital and if it’s part of their strategy. But the cap table concern that many downstream investors have will be exacerbated if the venture studio does follow on and retains a big equity stake.

Side Note: What happens when VCs start building venture studios?

Recently, Greylock announced a venture studio like program called Edge. It’s a “3-month company-building program designed to advance select pre-idea, pre-seed and seed founders from inception to product-market fit, with fully flexible financing.”

I have no issues with VCs getting into the startup building game. They understand the math all too well and see an opportunity to leverage their resources to help founders build from scratch. Recently I’ve heard of several VCs looking to put millions of dollars into founders / startups at the formation stage. For the founders looking at these deals, here are a few things to consider:

Follow-on capital and signalling. If a VC incubates your startup and then chooses not to follow on in a subsequent round, what’s that tell the market? It’s not a good sign. So be clear about how follow-on is handled to mitigate any negative signalling.

Board construction and startup management. Who really owns / controls the company in this scenario? Is it the VC and you’re a “hired gun CEO” (which isn’t necessarily a bad thing!) or is it really “your baby”?

Value-add the VC is bringing. Every VC claims they’re “value add.” I have yet to see a single VC say, “We provide no value other than the money,” (although that would be a bold statement!) “Value add” as an investor is very different from “value add” as a co-founder/company builder/venture studio. Make sure you’re clear on what you’re actually getting from them.

Here’s my take: Building startups from zero is insanely hard. Most VCs do not have the stomach for it, even if they’re intrigued by the entry points and upside. Investing—at any stage—is a lot easier than rolling up your sleeves, getting dirt under your fingernails and building. As the venture studio hype continues, more and more people will jump into the fray, but being a good investor and a good company builder are different things, unless you’re really committed to marrying these disciplines together.

What’s Really Going on with Cap Tables?

I struggle with the math when a venture studio takes 40-50%+. It feels unfair to founders. And I know future investors won’t like the cap table. But why is that the case?

The “party line” is that the CEO/founder (and key leadership) won’t have enough equity as the startup raises more capital. The CEO/founder gets too diluted and then decides it’s not worth it to keep going. I know this happens, but it’s rare. I’ve never worked with a founder that’s quit because they had too little equity. I’ve been involved with founders that wanted more equity and the investors / Board ideally try to re-up the founder (and/or key leadership) through the ESOP (employee stock option plan).

While I don’t think most founders quit because they get too diluted, I also don’t think it’s fair for a founder to grind for 7-10 years to make everyone else rich and not get properly rewarded. In fact, all early stage employees deserve more equity.

Founders have to appreciate what they’re doing by taking money from someone else—they now have an obligation to generate a return—but not, ideally, at their own expense. And while investors will argue on behalf of the founder (“They’re going to get too diluted because the venture studio already owns X%”) there’s something else going on. Some VCs don’t like the idea of generating bigger returns for the earlier VCs. Some VCs don’t like the idea that an earlier stage investor (studio, VC or otherwise) will own more equity than they do. I don’t think these VCs genuinely care about the founders; they care more about their own ego and ownership stakes compared with other investors (even though those investors committed earlier and took a much bigger risk).

Here’s the other truth: No matter what value a venture studio provides at the earliest stages, the success or failure of every startup is dependent on the founder and the leadership team.

Venture studios aren’t built to see a venture through from inception to exit (unless it’s a very early exit). It doesn’t work that way. Venture studios (like VCs) are playing a portfolio game. At some point they have to “let a startup go” or “graduate the startup out of the studio” and hope the founder + leadership team win. A good venture studio puts a startup on a strong path to success, de-risking key components of the business, but it can’t see the startup across the finish line.

Venture Studios Can’t Use a Traditional VC Business Model (Exclusively)

How do venture studios actually make money? It’s an important question because this is what most studios will struggle with going forward—they won’t find a sustainable business model that keeps them afloat.

In my post on the different types of venture studios, I shared a few options for how venture studios can generate revenue and build a business model:

Raise lots of capital: A number of venture studios take this approach; they raise capital to fund operations. This tends to look more like a VC fund (whose main source of “revenue” is from LPs investing.) While a venture studio would have to use a lot more of the capital it raises for operations (compared to a VC fund), the argument is that the studio will generate significant returns (in a de-risked way) to its investors.

Take “kick-backs” from startups: Quite a few studios invest money in startups but then charge a fee for the “program” and/or the services they provide. They need to invest more capital to earn equity, but then get some of that back to pay for operations. I completely understand why venture studios use this model, but I’ve always found it a bit uncomfortable.

Generate revenue in some other way: Some venture studios build revenue-generating businesses, which allows them to fund operations. These businesses could be thought of as “side hustles” or they might be strategically connected to the core value proposition of the venture studio. For example, a venture studio may generate revenue working with corporate partners, and then leverage those relationships to support the startups it creates.

According to a report by Max Pog, venture studios need at least $1-$2M to get setup, or better, $5-$10M.

As per the GSSN Data Report 2022, the median annual budget for a startup studio is $1.36M, the average – $2.49M. A venture studio co-founder in California revealed that they raised $2.5M in 2021 to create 4 companies and $6M in 2022 to create 6. Meanwhile, a co-founder of a startup studio in Luxembourg shared that it takes about €200K to launch one startup to the point where it can attract external seed investment.

$1-$2M is low. Even if that’s just for studio operations and not for investing into the startups, it’s not a lot of money. You can probably put together a small team of 3-5 people for that amount, plus the additional costs of running a company.

Don’t forget, you need this annually. If you use the same advice you’re giving founders—secure 18-24 months runway if you can—you need $1.5-$4M of capital just to keep the lights on. And in very quick order, you’ll be fundraising again.

Remember: you haven’t invested a single dollar into any startup yet. Assuming you’re doing that and not just taking equity for the work you put in, it’s safe to say you need to double the above budget; so having 18-24 months runway will cost $3-$8M. We haven’t even discussed how many startups you’ll be able to create with a small team and a tight budget. One per year? Two? Five? Ten? It’s tough to say, but in my experience most venture studios are overly optimistic about how many companies they can create.

Let’s assume for a moment that you have a $3M annual budget for your studio ($1.5M to costs, $1.5M intended for investment). You want to create 4 companies per year (investing $375k into each). When you include the operational expenses, it’s as if you’re putting $750k into each startup. If you take 20% of each startup upfront in exchange for $750k (half in investment; half in sweat) you’re doing quite well, because you’re investing at a $3.75M pre-money valuation, which is low and gives you meaningful upside.

But if you only create 2 companies in that time, investing the same cash into each (you ended up with a higher burn than expected), suddenly you’ve put $1.5M into each company for 20%, which is tantamount to a $7.5M pre-money valuation—much higher, and the startups you’re investing in are only a few days old.

Note: The higher operational cost of running a venture studio is part of the reason studios believe they deserve 40-50%+ of the startups they create and fund. I get it, because you have to earn enough equity for the “sweat” and for the dollars invested. But from a founder’s perspective it’s not their problem that a studio’s operational burn is where it’s at. Sure, those founders want the value, and they deserve it if they’re joining a venture studio, but your costs are not their burden to bear. In my experience this is a tricky balancing act between demonstrating why you deserve the equity and supporting founders’ interests.

When going to raise capital for a venture studio, it’s a different pitch to investors (think: LPs / Limited Partners, although you might not structure your studio as a traditional fund) because they’re used to typical VC fund math, which pegs management fees at ~2%. The difference is significant compared to the operational costs of running a venture studio. (Note: I’m not privy to the operational budgets of most venture studios, and I’m not suggesting it’s always 50% of the total budget, I’m using the number as an example.)

A venture capital firm has a pretty straightforward business model predicated on growing AUM to reap more management fees. It makes perfect sense. Venture studios can’t leverage this model as clearly, in part because of the high operational costs.

I believe we’ll see more and more venture studios explore business models beyond management fees. They’ll look for ways to offset the operational budget of running a venture studio and simultaneously try to grow AUM in creative ways (i.e. sidecar funds, SPVs, syndicates, etc.) While this makes sense, it’s also a risk because it can distract from the job of building and funding startups. Venture studios end up with three business models stacked on top of each other:

We’ve spent 7 years at Highline Beta building this, and we’ve still got lots of work ahead of us. But the pieces are falling into place through a ton of iteration, learning, etc. and I’m confident in our model and approach.

Part of what I enjoy about venture studios is the creativity of the business model. You don’t have to rely exclusively on management fees and growing AUM. I expect we’ll see a lot of innovation in the venture studio model and how venture studios make money over the next few years. This is needed innovation in a startup world that’s looking for alternatives to the VC financing route.

We’re also seeing more investment into venture studios, which makes complete sense to me. It’s a newish asset class that’s emerging quickly. Comparing studios apples to apples is tricky (because every studio operates differently), but ultimately it’ll be about returns (same as VCs). If a studio cannot generate meaningful returns for its investors, it won’t succeed.

There are other strategic benefits to investing in studios, which some investors will find appealing, including access to very early stage deals, proprietary deal flow, deep industry knowledge and more. Some investors will be attracted to the potential for venture studios to be self-sustaining businesses beyond management fees, which gives them a solid foundation. The venture studio model is getting more attention as a viable, systematic and financially smart way of building companies. Ultimately it comes down to investment returns, and the speed with which those returns happen. Venture studios, given their equity positions and how the math works, will rely on earlier liquidity through secondaries and early exits to drive faster returns and further enhance their sustainability.

I’m excited about the future of venture studios.

We need more company creation (not less) and there’s a gap in the market, globally, for providing a diverse group of founders with the necessary support and capital they need. Venture studios fill that gap, and can prove themselves to be a good investment. Will all studios succeed? Of course not. Everyone can’t win. I’ve already predicted that many of them will disappear over the next 3-5 years because the model is incredibly difficult to pull off. I can’t stress that enough—building and scaling a venture studio is crazy hard. But those that persevere, adapt and innovate, balancing founder-friendly terms with the right level of service for those founders, will survive and thrive, creating incredible value for everyone involved.

Solid post and insights. Thanks for shedding light on venture studio model from a well grounded point of view. In the end, startups and their founders deserve to win.