From Empathy to Scale: What Stage Are You Really At?

A deep dive case study on applying the 5 Stages of Lean Analytics. (#64)

Last week, a reader sent in a great question about business models and validation stages. While the focus is on ecommerce, the question (and lessons learned) apply to all business types:

I read the Lean Analytics book and I have one question regarding which stage a large company should focus on.

We have been working for this client who doesn't have a problem with acquisition. However, 85% of users make only one purchase.

They also have a problem with Stickiness, because there is 70% of churn rate after 3 months. And after 4 months, they only have 15% who continue their subscription.

My question is: because they are a large company not a startup, should they focus on Empathy or Stickiness?

I asked for a bit more information:

This is an ecommerce business selling at-home skincare devices and skincare products

The device is typically a 1-time purchase, but the skincare products should be purchased repeatably, ideally on a monthly subscription

They’re based in Latin America

The 5 Stages of Lean Analytics

First, let’s cover the 5 stages of Lean Analytics, and what this person is referring to when mentioning “Empathy” and “Stickiness.”

In Lean Analytics, Alistair Croll and I identified five stages that every startup goes through, along with “gates” that you need to go through to move between stages:

Empathy: The starting point, where you’re doing problem validation and understanding users’ pain points. It’s mostly qualitative through problem interviews (can use stimuli / concepts / prototypes) and research.

Stickiness: You build the MVP and give it to your early adopters (hopefully you’ve identified a narrow target segment during the Empathy stage). You’re measuring usage and trying to determine if the product is solving users’ problems. Think of this as Problem-Solution Fit.

Virality: Now you want to expand beyond your early adopters to acquire more users/customers. You’ve identified at least 1 channel that works and can scale (i.e. the more you use it, the more users/customers you acquire). You have to make sure that the new users you acquire are “good users”—i.e. they behave the same way as early adopters. Sometimes at this stage you’re able to acquire a lot of users, but they churn out fast—it might look like you’re winning until everyone disappears. (Note: In hindsight we probably misnamed this stage and it should have been called “Growth” (or something else), since virality isn’t always possible or even the focus of user acquisition.)

Revenue: At this point you need the economic engine to work, or you need line of sight into it working. You’re not necessarily profitable, but the underlying economic metrics look good. The context depends on the type of business you’re in. For example, a B2C business using an advertising revenue model will track different metrics than a B2B prosumer freemium business.

Scale: You’re post Product-Market Fit and growing a lot. You may be expanding into new geographies or launching new product lines. Perhaps you’re building a platform / ecosystem. There are a variety of ways to scale.

Here are a few common mistakes founders make:

Half-assing the Empathy stage: Most people agree with the idea of engaging users first, figuring out the problem and then building something for them. But calling your Mom and asking her if your new startup idea is good doesn’t count. Or casually pinging five friends. People don’t like being rigorous at this stage because:

it’s a lot of work;

you’re not building anything yet (and most founders 😍 building!);

no one wants to be told their idea is stupid.

Jumping to Virality too quickly: Most startups fail at Stickiness, even if they raise a ton of capital and keep going. Why? Because they’re not solving a problem that actually matters. Yet they’ve managed to grow (perhaps spending their way into it) or convince themselves they can grow, so they rush to the Virality / Growth stage to acquire as many users/customers as possible. It’s a house of cards that eventually collapses.

Never proving the economic engine works (Revenue Stage): A lot of startups can’t get to the stage of proving the economic engine of their business. This is often the result of raising a lot of capital, then spending a lot of capital, only to realize that either the fundamentals of the business aren’t working or things have changed during the journey and what was once true isn’t anymore (and the math is breaking). This is really the stage of getting to sustainability; i.e. the business works, you can prove the financial model and you’re scaling. No surprise, this is insanely tough to achieve.

Back to the Ecommerce Business: What stage are they really at?

My guess: They thought they had Product-Market Fit because of how easily and quickly they were acquiring users. It’s a classic case of “premature scaling” which affects a lot of B2C businesses.

Only when they realized that everyone was churning did someone put up their hand and say, “Um, we may have a problem.”

Here was my response to the original question:

1. Skincare device: sounds like a 1-off purchase (i.e. they don't have to keep buying more and more devices); so that makes sense.

2. Skincare products: usually these are meant to be repeat purchases (either on subscription or not). Sort of like the razor blade analogy - sell the handle once, sell the blades over and over. So this part is concerning, especially if the skincare products are meant to be used with the skincare devices; i.e. if they stop buying products repeatedly, they've probably abandoned using the device. If that's true, it's very bad.

They have to figure out WHY people aren't coming back to purchase again. That's a Stickiness issue. If they can't figure that out, it might be a more fundamental issue, which is that they're not solving a real problem or they are solving a problem but not well (i.e. the products aren't good enough). So it's a Stickiness issue first - try and figure out why people aren't buying again, and experiment/iterate there.

I don't know enough about the specific products either; so perhaps after 3 months a lot of people have their problem solved and simply don't need to keep buying. That's probably not the case though. It sounds more like:

* People buy b/c they think it'll help them. It's a somewhat impulse buy (maybe not too expensive)

* They try it and it doesn't deliver enough value / solve the problem enough and they churn.

I would try and talk to users and understand why they’re abandoning. To some extent that is about gaining empathy. But the acquisition suggests people are at least interested in what’s being offered, but then get disappointed after.

To be clear, every time a company of any size puts out a new product it should go back to the Empathy stage and make sure they’re solving a problem that matters.

Big companies often don’t go through the fundamentals in a rigorous way because they believe their scale will solve any issues that emerge. Big companies, especially legacy ones (that have been around for a long time) under-value the Empathy and Stickiness stages and over-value the Virality and Revenue stages, often attempting to leapfrog the early stages to grow as quickly as possible. It rarely works.

Understanding Ecommerce Businesses

In Lean Analytics we covered the ecommerce business model and mapped out how it works and what metrics matter the most. But not all ecommerce businesses are the same. Kevin Hillstrom at Mine That Data (read his blog!), helped us dig into things in a lot more detail. Through his research, he identified 3 types of ecommerce businesses:

Acquisition: Mostly focused on acquiring customers, the business isn’t designed to drive tons of repeat purchases;

Hybrid: A business that sits in the middle, with some degree of retention, but it’s not super focused on that;

Loyalty: Focused entirely on driving repeat purchases.

You’d think that every business would want to be in the Loyalty category, but that’s not necessarily the case. In fact, most ecommerce businesses aren’t (although I’m sure some of them would like to be!) The point is that Loyalty ecommerce businesses are not necessarily better than Acquisition ones; they’re just different. They have to operate differently and track different key metrics.

This is data we published in Lean Analytics (back in 2013). I reached out to Kevin to see if things had changed, and he wrote back, “Nothing has changed … same dynamics, as it has always been in the direct-to-consumer world.”

The beauty of this data is that one single metric, in this case 90-Day Repurchase Rate, gives you a strong indication of the type of ecommerce business you have, and consequently what you should focus on. (Note: these numbers aren’t specifically focused on subscription businesses.)

For example, if 1-15% of people repurchase from you within 90 days, you’re in the Acquisition business, which means you need to focus on low cost of acquisition (you can’t pay a lot to acquire customers that don’t come back) and high checkout rate (you have to drive as many users as possible to buy something). You might also have a higher price tag on items so that each purchase is significant.

Recently, I bought luggage online. I don’t buy luggage often (every ~5 years or so?) and I can’t imagine most people buy luggage frequently. A luggage ecommerce site is an Acquisition business—it needs to acquire customers inexpensively, convert a high percentage of them (with luggage it seems like there’d be strong purchase intent), and have decent basket size (i.e. $200-$600/purchase). Of course this luggage site is still going to get me to subscribe to their newsletter and send me weekly/monthly updates, but how effective can that really be? I just don’t buy luggage very often.

Exploring Benchmarks

It’s always interesting to find relevant benchmarks for your business. I did some digging into ecommerce beauty & personal care businesses and found a few interesting statistics:

Overall retention rate for beauty brands is 23%. “Beauty is a sector, notorious for customer disloyalty. This is due to two interconnected reasons: people believe cosmetic products stop working after awhile and thus they are eager to try new things in hope they’ll work even better: a new hair color, a new scent of perfume, a new face mask, etc.” (Metrilo)

Retention after four months for beauty & personal care is 59% (from Recharge)

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) for skincare is $176. That feels very low to me and makes the cost of acquisition even more important. (from Metrilo)

40% of capital raised by DTC businesses goes directly to Meta and Google for acquisition (and it costs 7x more than it used to) (from relo)

Benchmarks are never perfect. The data may be outdated or not specific enough (i.e. by geography, category, etc.) but it helps give you a sense of where you’re at. Ultimately, even without benchmarks you can tell if your business is doing well or not using simple math.

In this case, the business in question only has 15% retention after 4 months, which clearly isn’t good enough. As a result, Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) is lower than Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), which is a recipe for disaster (they lose money on every customer acquired).

The company has two ways to make the math work:

Lower acquisition costs

Increase retention

First: Map Your Business

Before deciding on what to do to improve your business, you should map it. There are plenty of experiments you can run, but how will you prioritize them and measure their impact? If you map your business (as a system) you can identify the trouble spots and focus your energy there.

For more on how to do this, read: Your Startup is a System You Can Map to Identify Problems, Align the Team & Win

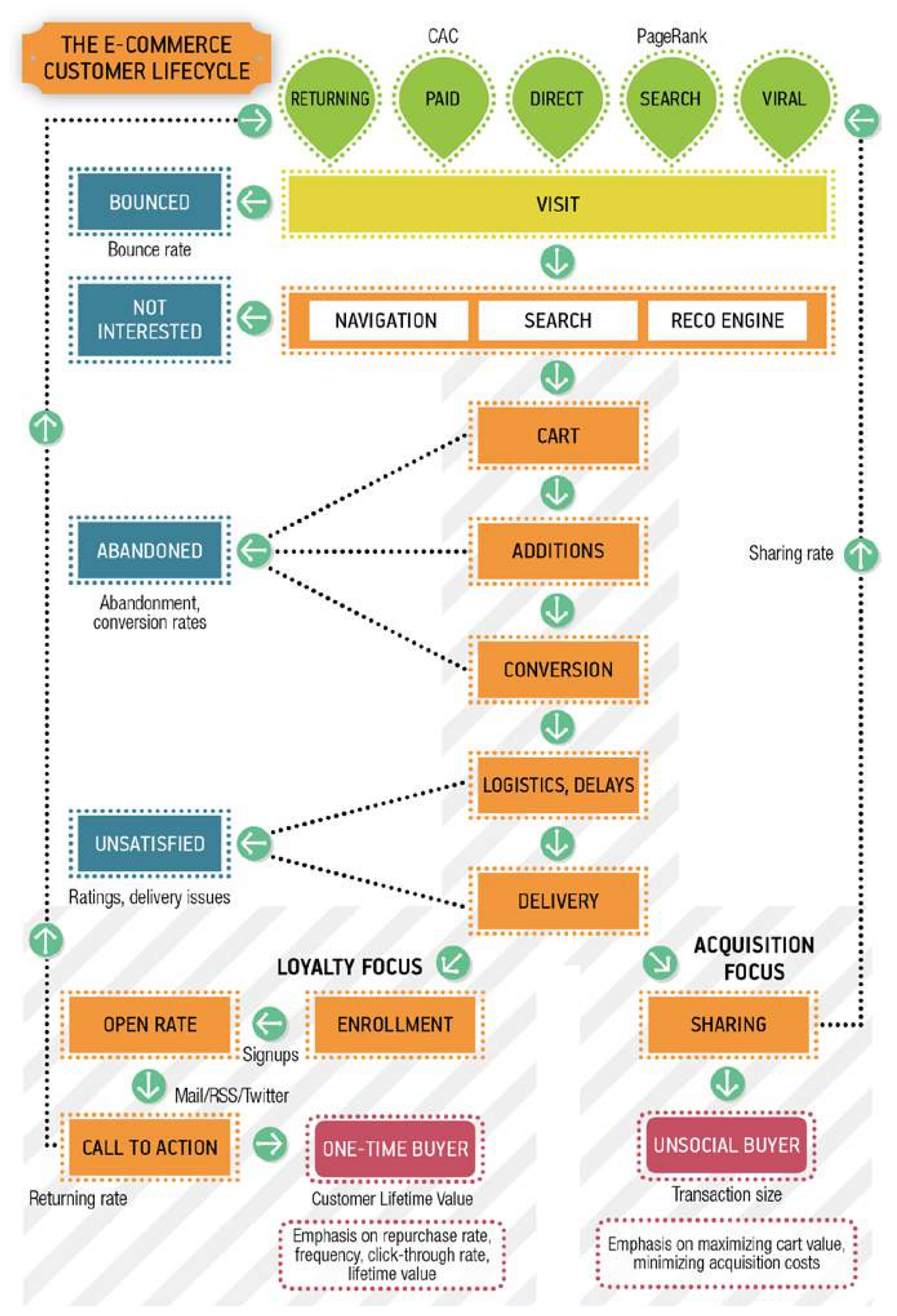

Here’s the original ecommerce systems diagram from Lean Analytics:

The basic structure of your ecommerce systems diagram may look somewhat similar, although a few things will change (for example, influencers weren’t really a thing when we published the book!) This diagram is also fairly simplistic. For example, it doesn’t include options for re-engaging people who abandon the site or abandon their carts (via email marketing, exit popups, etc.) So your systems diagram should have more detail.

My recommendation to the person that sent me the question was to first map out their business—the entire customer journey—and get a feeling for where things are breaking. That will help them figure out where to experiment.

Second: Run Quick Experiments

Once you’ve visualized your entire business and identified the trouble areas, it’s time to experiment. The trouble areas should be identified through quantitative and qualitative data, so make sure you collect the data you have and talk to customers (including current / happy customers and ideally, churned customers, if they’re willing to speak with you). With the data in-hand, you can prioritize experiments.

Note: If you realize when talking to users/customers that your products aren’t good enough, most if not all of these experiments won’t work, because the fundamental value proposition is broken. In that case go back to the Empathy stage to better understand the pain points and then make sure you’re delivering enough value as you move into Stickiness. This could result in significant product changes.

Assuming the products are good (and in fact solving the pain points), here are some experiments that may help with reducing churn:

Change the price: Should the price be higher? Lower? Would that impact retention/churn?

Product bundling: Are there better / smarter ways to bundle products? Do people who frequently buy X also buy Y?

More precise customer segmentation to acquire better users: I’m a big fan of identifying your best users, figuring out what makes them different/special and using that to acquire similar users. Do you have die-hard fans? What makes them special?

New acquisition tactics / channels: I was told that the business is acquiring most of its customers through three channels: Direct, Google Organic and Facebook. What about influencers, referrals or other channels? I’d also want to better understand “Direct” and what that means.

Move off the subscription: This would be a more radical option, but they could try selling a bigger cart size upfront (increase Average Order Value/AOV initially) knowing that the user is likely to churn (i.e. stop trying to be a Loyalty business and become an Acquisition or Hybrid one). Or perhaps there is subscription fatigue (which you can learn qualitatively).

Increase personalization: Personalization has been proven to increase retention for ecommerce businesses, so perhaps there are things that can be done? Options include: quizzies, dynamic content / visuals, personalized email marketing (based on behavior), wish lists, virtual try-ons, etc.

Increase engagement: Are there ways to increase engagement in-between purchases, such as providing educational / how-to content that enhances the customer experience? What about a loyalty program that earns you rewards the more you purchase (assuming you’re building a Loyalty business)?

You can’t run every experiment at once. So you need to prioritize. There are a variety of prioritization frameworks, including RICE:

Ultimately, you should pick the experiments that you believe will have the biggest impact with the least amount of effort. You’ll probably run a few experiments in parallel, but ideally not completely interfering with each other and complicating the results. Once you’ve prioritized, the key is to execute the experiments as quickly as possible to increase the frequency of learning (more learning = higher chance of winning).

And now, a science experiment joke:

Love the article but I hate RICE!