Do Big Markets Matter for Early Stage Startups?

Yes, but not initially. And pitching your 1% market share plan in a big market is a recipe for failure. (#21)

Almost every startup pitch includes a slide on market size. The goal of this slide is typically (and unfortunately) to demonstrate how big the market is and how well positioned the startup is to attain a chunk of that market.

Does the size of the market actually matter?

Yes and no.

Let’s first explore why focusing on a big market is a mistake.

1. Defining Markets is Hard

How do you even define a market or the market size?

The global MarTech (marketing technology) industry is worth between $321B-$510B according to various research reports.1

For starters that’s a pretty substantial range, but it’s also difficult to know what’s included. If you provide software for automating tweets and LinkedIn messages to help people improve their social media efforts, you’re probably categorized as MarTech. So would you say that your startup is in a $321B industry?

You can try, but that’s pretty silly.

Another approach is to define a sub-category inside MarTech. For example: Marketing Automation Software.

That’s a lot more relevant to the solution above (automating tweets and LI messages), so we’ve narrowed our focus.

The market size is estimated between $5.8B-$6.5B in 2023 with a CAGR of 12.3% (CAGR = Compound annual growth rate.)2

That’s a much more reasonable market size because you’ve narrowed down into a sub-category (Marketing Automation Software) but what does this really tell us? Honestly, not much.

TAM, SAM, SOM - What the f**k?!?!?

Most startup pitch decks will try and define the Total Addressable Market (TAM), while others will go a bit deeper and also define the Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) and the Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM).

What the hell are people talking about?

TAM = The complete market (often at a high level; sometimes called the total available market), this is the overall revenue opportunity that is available to a product or service if 100% market share was achieved.

SAM = The portion of the TAM that can be served by a company’s products or services.

SOM = The portion of the SAM that can be realistically captured and served. This is typically a shorter term goal based on the products/services and scale you have today.

Note: There are varying definitions for TAM, SAM & SOM, which makes things even harder to understand. And the definitions are typically focused on “top-down sizing” which is confusing and rarely relevant.

Often SOM is restricted by specific criteria, such as: (1) geography; (2) customer segment; and/or (3) the sophistication of the product (i.e. you only have an MVP and can’t capture all the value in the SAM or TAM initially.)

Note: One of the problems with top-down market analysis is that it usually defines too broad of a customer segment. “Small business” is not a market. It’s simply too vague—but it might be hard to figure out the number of small agencies in the U.S. with 10+ clients that focus on social media marketing related to e-commerce (which is a much better early adopter market definition.)

If you insist on using TAM-SAM-SOM (🤮), recognize that SOM is the only thing that matters. And I still don’t think it’s niche or narrow enough.

Venture capitalist, Sara Ledterman nails it (the thread is great too):

Markets are complicated but easy to oversimplify

I came across an epic LinkedIn post by Robert Kaminski walking through the realities of market sizes using Calendly as an example.

In Calendly’s case the TAM might be “everyone who books meetings as part of their work” (so practically everyone.) If you narrow down to the SOM, it might be “sales teams scheduling meetings with prospects,” which you can start to wrap your arms around. But things aren’t that simple, because there are so many other variables to consider including company sizes, industries, sales models, meeting types, etc.

What becomes evident is that TAM-SAM-SOM is a gross oversimplification of how markets work. And while that oversimplification might look clean in a pitch deck, it doesn’t help you run your business.

The market you’re actually going after impacts everything, including your value proposition, go-to-market strategy, product roadmap, pricing, sales strategy, etc.

If you get the market wrong, you’re going to end up wandering the desert. This is why I’m a huge fan of niche markets (more on niche markets in a moment.)

2. The 1% of a Market Fallacy

One of the common mistakes startups make when they focus on a big market is the “1% market fallacy” which goes something like this:

“The X market is absolutely huge and growing quickly.”

“All we need to do is capture 1% of that market and it’s going to be worth billions. Billions, I tell you.”

In the immortal words of Kenny Bania, “That’s gold, Jerry! Gold!”

So what’s the problem with saying you’ll capture 1% of a giant market?

1% of a big market is still a huge number, and it’s incredibly difficult to get there. Further, without any real focus other than capturing a small piece of an enormous pie, you’re again wandering the desert picking up scraps.

If it was that easy—and often founders present this as a very achievable goal within a few short years—literally everyone would be doing it.

A tiny piece of a giant pie is the wrong way to think about things. Instead, you should be aiming for a big piece of a small pie, initially, and then figure out how to take other chunks of other pies after that.

3. No Unfair Advantage within a Big Market

The final challenge with focusing on a big market is that most early stage startups (and even later stage ones) have no legitimate unfair advantage. You quickly become another player in the space clawing to get that mythical 1% market share.

You should never start a company on a level playing field.

It makes no sense to jump into a market without any advantage whatsoever, and yet many people do. They see a gigantic market, figure they’re smart and capable, and go for it. Those founders usually get chewed up. While a lot of startups aim to compete on speed versus incumbents it’s rarely enough on its own.

How I started a company in the recruitment space and failed (in part because I didn’t understand the market)

I won’t go into all the gory details (you can read more in my postmortem analysis here and here.) But when I started Standout Jobs in 2007 I rationalized it as follows:

“The recruitment market is massive” (true)

“Every company struggles to find great talent” (also true, but not a real insight)

“We’re smart, we can win in this space” (ouch 😭)

It’s not that we weren’t smart, it’s that we didn’t understand the market well enough. We had a superficial understanding of HR and recruiting, which was one of the big reasons we struggled and ultimately failed.

We had no real unfair advantage in the market. “Being smart” doesn’t count! Neither does “building cool tech.” Had we focused on a narrower market and understood their pain points deeply, perhaps we would have had a chance.

In a big market there are going to be big incumbents. While you might look at them as dinosaurs you need to remember two things:

They won (and won big)

They want to hold onto their winnings as much as possible

They’re not always successful at holding on, but most of the time they do, even if they’re slower, more risk adverse and out of touch. The big companies do alright. Being dismissive of them will get you killed.

A Quick Summary of Why Focusing on Big Markets is a Bad Idea

I definitely appreciate the appeal of big markets. Those 💰💰💰 look so exciting!

But chasing a big market—certainly early on—is a mistake.

It’s hard to define a big market and really understand your place in it. TAM, SAM, SOM is generic and doesn’t do justice to how markets really operate.

Focusing on a big market likely means you have a superficial understanding of users/customers, their needs and what will get them to try & buy your solution.

You set what seem like reasonable expectations (i.e. 1% of a big market) but it’s a meaningless number, and still almost impossible to achieve.

You have no real advantage in a giant market because there are too many competitors with too much money, history and control.

So what should you do?

Focus on a Niche

I’m a fan of small markets. Not because I’m hoping you build a small company, but because they’re easier to define, understand and serve. I can wrap my head around a small market because the user/customer, problem, go-to-market, value proposition and solution all become much clearer.

Small markets drive focus: You become an expert in that niche, which provides you with an unfair advantage over the competition. You go so deep into a market that you know it better than anyone else. You become laser-focused and can ignore the swirling noise around you.

Small markets move faster: Gaining traction in a small market is like a snowball rolling down a hill. You build momentum in a small market, become well-known, increase referrals & reputation and can start scaling meaningfully.

Small markets may become big markets: Markets aren’t set in stone. Small markets shift regularly and some of them will become big. If you only look at a big market (i.e. the global CRM software market is ~$60B3) it’s somewhat hardened. You won't shift that market; but you can influence and affect small markets, and those markets are prone to more rapid change, which you can use to your advantage.

Small markets may already be fairly big markets: You can over-segment a market and go after too small a niche, but in some cases a “small market” may already be quite big. Those “small/big markets” are probably underserved.

Small markets are great starting points. If you can dominate a small market, you have a chance of expanding from that market to another. I think of small markets as a wedge—you need to be in the game to have a chance of winning.

Going after a niche or small market size is more cost effective and (assuming you have the right solution, value proposition, go-to-market strategy and business model) easier to gain real traction.

Rick Zullo, Co-Founder and GP at Equal Ventures writes in a post, “Niche is the Next Big Thing”:

“There are already plenty of challenges for founders to face. Don’t make taking on an army of competitors for the sake of justifying ‘TAM’ another one of them, unless you know you’ll have the resources to win that war. With leaner times undoubtedly ahead, we expect an increasing focus on capital efficiency in the years to come and know that niches provide a pathway for founders to achieve growth AND efficiency, not just momentum amidst a flooded market of competitors that requires hundreds of millions in capital to simply exist. With capital getting tight in 2023, we think ‘niche’ could very well be the next BIG thing.”

Sarah Tavel, GP at Benchmark has an awesome analogy on markets, “find a fast current, not a large body of water.”

“Often we talk about markets as if we were speaking about a body of water — a description of the size or depth.

I’ve found it is far more useful to think of markets instead like a river with a current. As a founder (the ship’s captain), your job is to find the current, and then build the best ship (product) and team to ride it.

A strong current makes the actual job of being the captain a heck of a lot easier. You could have a plank of wood to start in a strong current, and you’ll still move a lot faster than a slick boat in stagnant waters.”

Small market aren’t inherently fast currents—so be careful about jumping into a stagnant one. But there’s a better chance that niche markets are faster moving than giant ones. With the current pace of change (especially tied to the torrid river that is Generative AI), I believe that big markets are being fragmented more aggressively than ever before.

How to Pitch Market Size

For early stage startups, I always prefer seeing a bottom-up analysis of market size.

Instead of saying, “We’re in the Marketing Automation Software space, which according to so-and-so is worth $XB” you calculate:

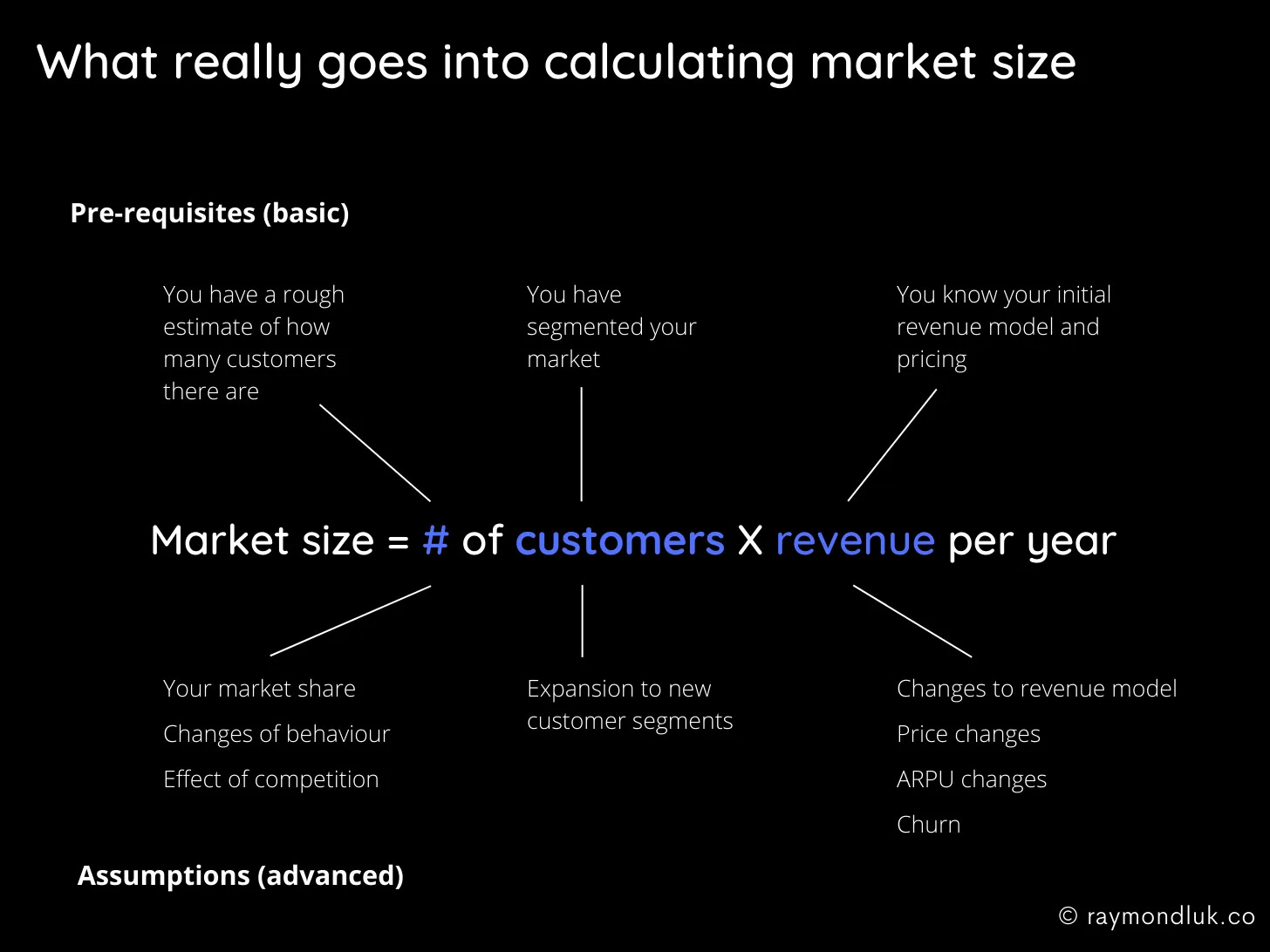

Number of customers (in a specific segment!) x Revenue per yearThis looks fairly simple but there’s a lot that goes into it. Raymond Luk does an excellent job of visualizing this:

You should read his entire post: The Market Size Dilemma

And then read Pear VC’s post: Market Sizing Guide

Here are the things I like to see on a Market Size slide in an early stage startup’s pitch:

A bottom up analysis as described above

Over a period of 3-5 years (i.e. what you believe you’ll capture; not the total market size during that time)

With a story on how you intend to expand from one niche market to a next (i.e. the growth story)

All of this is designed to understand the underlying assumptions that have gone into defining market size, and connecting the dots between the problem, solution, value proposition, business model and go-to-market/sales approach. Everything has to make sense and feel connected with some basis in logic:

The problem has to be well defined and clear, and specific to a particular user/customer/segment

The solution & value proposition have to reasonably solve the problem

The business model has to make sense in the context of how the solution will be used and the value that users/customers are going to extract

The go-to-market has to be aligned with all of the above (i.e. If you’re selling something for $5k and it takes 6 months, you’re 💩 out of luck)

Everything leads to a market size that seems plausible and achievable.

Why Getting Market Size Right is Important

It might seem from this post that the market size doesn’t matter. In fact it does. A lot.

Going after a giant market, or focusing on a mega-TAM of an ill-defined market is a bad idea & a waste of time, but defining a market is critical.

Your definition of a market size (and how you intend to grow over the next 3-5 years) reveals a ton about the assumptions you have for the business.

In an early stage startup (pre-seed / seed), the projections are always wrong. I’ve never seen projections actually match up with reality (often the projections are too ambitious, which is fine.) But good investors shouldn’t be looking for reality at this stage, they should be looking for solid assumptions and thinking.

Your market size ambitions over the next 3-5 years — i.e. what you hope to accomplish — leads investors to a better understanding of how well you know the business, the market and the opportunity. The conversation that comes from this is critical.

The Market Size slide is where an investor can stress test the underlying assumptions with you, and ideally provide feedback from their experience:

Is the growth rate reasonable? How will you achieve it?

Is the price validated? Could you charge more? How will you expand ACV (Annual Contract Value) in the future?

Why are you going after Segment A? Did you look at Segment B or C? Why are they different?

Is Segment A a growing/big market? Can you build a sizeable company just off Segment A alone?

How significantly will the solution have to change for you to move from Segment A to Segment B? How much of an investment will that be?

Do you know how to reach customers in Segment A? Do you know if that’s easier or harder than Segment B? Do you believe customers in Segment A will share with others? Could this go viral and lower CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)?

What’s the sales cycle look like?

How is competition positioned in Segment A, B or C?

And so on…

The Market Size slide is where everything comes together to tell a plausible (but still uncertain) story.

If you use it to demonstrate a giant TAM, SAM and SOM you’re missing a huge opportunity. And if you don’t have well-articulated assumptions underlying the market, investors won’t fund you.

So Market Size Matters, But…

The market size you’re going after matters, but not in the way you might think.

It’s not about top-down TAM, SAM, SOM calculations that make a weak attempt to prove the market is huge!

Niches are a great place to start for early stage startups. I love a niche that you, as the founder, understand deeply, can reach, and have proven interest from. I almost want to say “the smaller, the better” but with a clear caveat that if the market is too small, you won’t get the benefits of dominating it (think back to Sarah Tavel’s fast moving river analogy.)

Markets change, shift and grow. Trying to overly define them or put them “in a box” is silly. And there’s a good chance as your startup scales that you realize you’re in a different market than you originally thought. That’s totally fine (as long as you figure it out quickly enough!)

Defining a market size in your pitch deck is primarily about helping investors understand your underlying assumptions, which frankly, leads back to why investors should be investing early stage anyway—the people. If you don’t have any good assumptions or any way of testing those assumptions, you may find investors questioning whether you’re the right person for the job. I much prefer seeing all the messiness, because it builds my confidence in the founder (as long as the founder is not presenting insane assumptions that have no basis in reality.)

If you’ve made it to this point you might think, “Amazing! I’ll just go find a small market and win.” I wish it were that easy. If you’re looking to build a category defining mega-company, you’re going to need to compete and win in big markets. You can’t build a billion dollar startup in a hundred million dollar market. To win big, you’ll have to win in a big market. But you shouldn’t start there. Even if you know ultimately where you want to go in terms of big market domination, trying to play in those big, nebulous markets early on will likely kill you.

https://www.perplexity.ai/search/1aa5e4bb-4a19-42f6-94e0-a9610ca68c83?s=u

https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/marketing-automation-global-market-report

https://www.perplexity.ai/search/2244a1ea-76e5-4d5e-8a65-44dee34176af?s=u

What matters is that they define the market differently and design solutions that get a "job" done better and more completely than existing solutions. More often than not, disruptive solutions will attack the problem completely differently, at a higher order of value, while having fewer visible features.

Think Spotify vs iPod vs component stereo systems.