Vibe Coding Without System Design is a Trap

"Measure twice, cut once" is still good advice, but AI tools make it so easy to break that rule.

Lowering the barrier to creation has always been a net positive. WordPress turned anyone into a publisher. YouTube turned anyone into a broadcaster. Shopify turned anyone into an e-commerce operator. AI-assisted coding is doing the same for product building.

Let a thousand flowers bloom. I’m all in!

The problem: AI is very good at helping you build something. It’s not very good at helping you build something well.

The difference matters, especially for founders, product managers and product teams trying to ship real products, not prototypes or demos.

AI Optimizes for “Working,” Not for “Evolvable”

When you ask AI to build a feature, it optimizes for one thing: making it work right now.

That usually means:

Hardcoding values instead of abstracting them

Taking shortcuts that reduce cognitive load in the moment

Ignoring future change, because future change wasn’t explicitly requested or anticipated

For example, it will happily hardcode configuration values directly into logic.

Recently, I built an Applicant Tracking System using Lovable (I’m a big fan) to replace the ATS we’re using at Highline Beta. Why? I thought it would be an interesting experiment, and we don’t need anything super sophisticated.

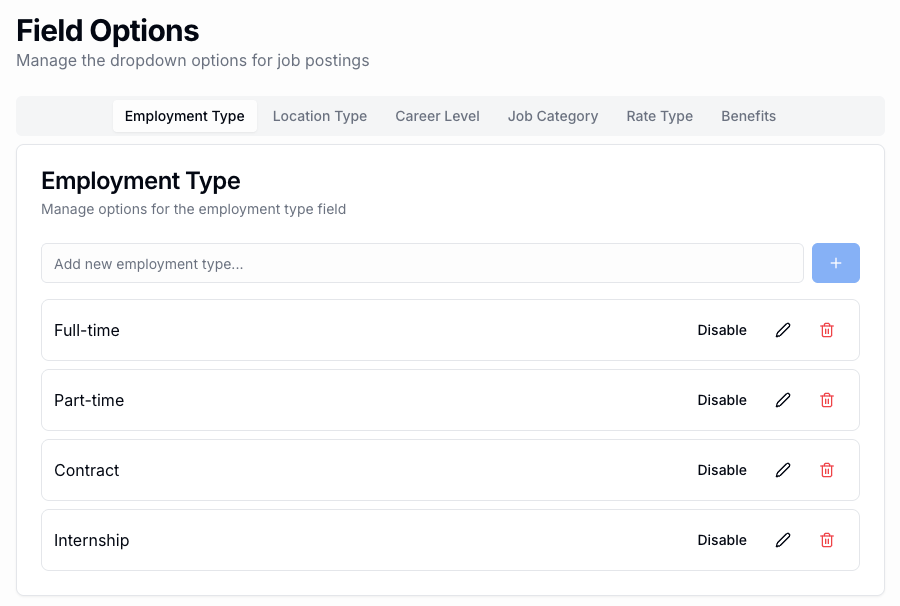

When I first created the ATS, I gave Lovable a list of job post fields, but I didn’t explicitly state which ones should be configurable by an admin. Lovable built the system with the fields, including Employment Type (e.g., full-time, part-time, etc.), Location Type (e.g., in-person, remote, hybrid), etc. but hardcoded the options. The moment I went to post a job and saw the predetermined field choices I knew the system wasn’t flexible enough. I hadn’t designed the system properly and the AI filled in the gaps for me.

You can prompt it not to do this.

You can tell it to introduce global settings, environment variables, or config tables.

But you have to already know that it shouldn’t be hardcoded. That knowledge doesn’t come from vibe coding. It comes from experience (which I have, but wasn’t using at that moment!)

The same pattern shows up with testing.

Out of the box, AI rarely builds test cases, test harnesses, or any meaningful testing strategy. It will generate (mostly) functional code that works for the happy path and quietly moves on.

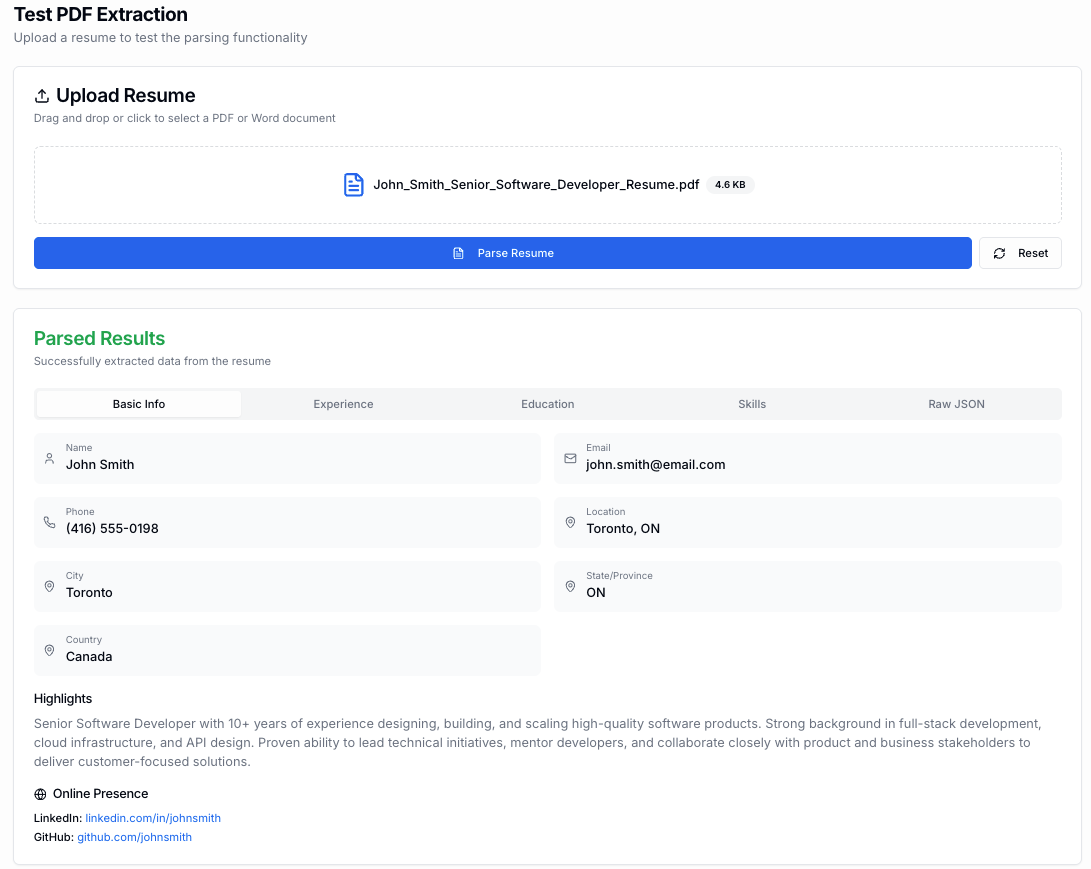

For the ATS, I wanted people to upload a PDF resume and have the system parse the data, minimizing what users have to input. I prompted Lovable to build the PDF parser into the job application form, which it absolutely did! I uploaded a few resumes to test it and quickly realized I had no clue what it was actually doing. In some cases it wouldn’t parse very much at all, in others it seemed to get a lot of data. I realized I needed a way to test PDF parsing deliberately, not accidentally.

So I built a Test PDF Extraction tool into the ATS. This made it a lot simpler to test this feature than constantly applying for jobs.

Again, you can prompt AI to build testing tools and it’ll likely comply (or at least try). But it won’t proactively design for testability unless you explicitly ask. If you don’t have much product building experience, you may not ask, or even realize you should, all the while building features atop features with little sense of what’s actually going on.

The Result: Functional, Messy Products

The end result is predictable—an explosion of products that are:

Functional ✅

Fast to build ✅

Easy to tweak superficially ⚠️

Painful to test ❌

Fragile to change ❌

Increasingly expensive to evolve ❌

Tools like Lovable make it dead simple to prompt changes. Iteration feels magical. You can vibe code your way through dozens of tweaks in an afternoon.

But there’s a real difference between:

Endless iteration through prompts; and,

Building something with coherent structure and intent.

Vibe coding optimizes for speed, not for load-bearing structures.

That’s fine for small DYI projects you’re doing for fun. It’s dangerous when you’re laying the foundation for a new house.

Vibe Coding Still Requires Systems Thinking

Vibe coding doesn’t eliminate system design, it pushes it into the background.

If you don’t think about structure up front, you’re still technically implementing one, you’re just doing it accidentally, which is dangerous.

System design is about how the product holds together over time.

It’s asking questions like:

Where do key settings live?

What should be configurable versus hardcoded?

How do different parts of the product depend on each other?

What happens when something changes six months from now?

What assumptions are baked into the data model?

These decisions don’t show up in screenshots. But they determine whether your product is flexible or brittle.

AI will happily help you build features without answering any of these questions. It will make things work. It will connect the dots you tell it to connect. But it won’t pause and say, “This should probably be a global setting,” or “This schema is going to be painful to migrate later.”

That judgment comes from understanding systems.

To vibe code successfully, you need a mental model of the system you’re building. You don’t need a massive architecture document. You need a rough map of what’s core, what’s shared, what’s likely to change, and what really shouldn’t.

System design is what keeps you from cutting off your fingers while moving fast.

5 Systems Questions to Ask Before You Vibe Code a Feature

This is the practical part most people skip.

Before you ask AI to build anything, pause and answer these five questions. Not in code. Not in prompts. Just in plain language.

What is likely to change later? If it might change, it probably shouldn’t be hardcoded.

Should this exist once or everywhere? If the same value, rule, or concept shows up in multiple places, you need to design the system to handle that. Build it once and apply it everywhere. Tools like Lovable will happily rebuild the same thing over and over, and even implement it differently each time, unless you’re explicit.

What is the source of truth? Is this coming from config, the database, user input, or assumptions buried in logic?

What breaks if I change this? If you can’t answer that, the system is already fragile.

How would I test this? If testing feels awkward or manual, the system design is probably the problem.

You don’t need perfect answers. You just need to ask the questions.

These five checks turn vibe coding from random motion into intentional progress.

Where a Product Requirements Document (PRD) Actually Helps

At this point, some people will ask: should I be writing a PRD?

The honest answer: I’m torn.

On the one hand I love writing things down, being thoughtful and explicit. I’m used to thinking about edge cases, error handling and “completeness”, despite my strong belief in the importance of MVPs. I’ve been building software for 30 years, I know where a lot of mistakes can be made. I’ve made a lot of mistakes! So being comprehensive and accounting for issues in advance sounds logical.

On the other hand, AI builders and code assistants are freaking magic. It’s incredibly rewarding to put a relatively straightforward prompt into a tool like Lovable and within 30 seconds get a full blown application. The urge to build quickly outweighs the urge to build carefully.

As is always the case, you need to use the right tool for the job. If you’re building a very complex, mission critical application that’s handling people’s money, think about using a proper, robust PRD. If you’re building a simpler app that won’t cause the entire house to collapse, do less planning.

I’m starting to experiment with a system sketch.

A one-page forcing function to answer the five questions above before AI answers them for you in code. A key part of this is understanding and defining the assumptions you’re making in what you’re building, why you’re building it that way and the implications. If you don’t provide this context to the AI, it’s going to guess. The key is to provide enough structure to externalize system decisions before they harden.

Interestingly, if you’re copying an existing product, you can use it as your PRD. Its structure encodes decisions about configuration, data and dependencies. That’s why copying something well-designed is easier than starting from scratch. I copied our existing Applicant Tracking System tool as a baseline for the new one. It helped me think through the system design and structure before prompting Lovable to build stuff.

Remember: You’re always vibe coding into a system, whether you’ve designed it intentionally or not.

For inexperienced product people, this is the real risk of vibe coding: not bad code, but accidental architecture. The old adage, “measure twice, cut once” is still good advice.

Edge Cases and Error Handling Are Where Products Become Real

Vibe coding quietly cuts corners in two places: edge cases and error handling.

Handling edge cases and errors is unglamorous, tedious work. You hope edge cases and errors don’t happen often, but dealing with them is what turns a prototype into something people can rely on.

When you vibe code, you’re almost always building the happy path where inputs are clean, assumptions hold, and users behave the way you expect.

AI is very good at this.

It’s much less interested in:

What happens when data is missing

What happens when inputs are malformed

What happens when systems disagree

What happens when users do something unexpected

What happens when the model is uncertain

Tools like Lovable will often add basic error messaging or guardrails. That’s helpful. But “basic” is doing a lot of work here. Production-grade products spend a lot of time dealing with the messy edges: partial failures, ambiguous states, retries, fallbacks, degraded modes, unclear outcomes, etc.

These aren’t afterthoughts. They’re core product decisions. Vibe coding diminishes their importance quickly, because everything feels like it’s working… until it isn’t.

Let me give you two examples: one simple, and one more complex.

Simple Example: Field formatting

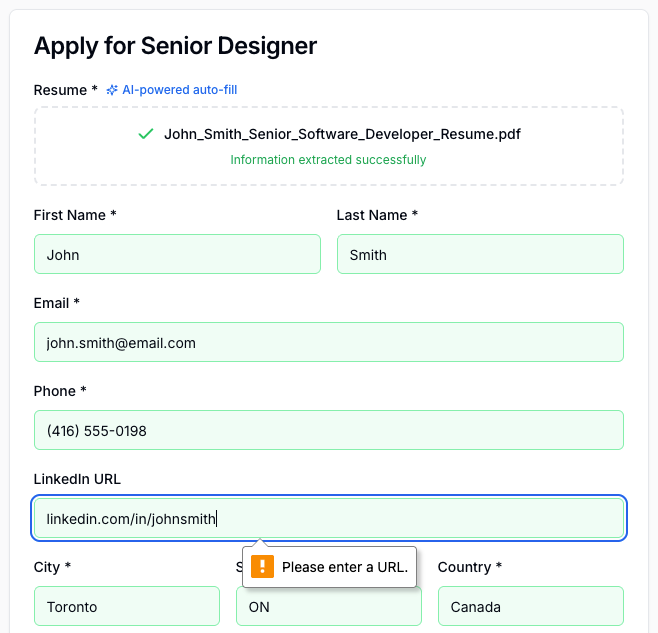

Here’s John Smith applying for a Senior Designer role:

The PDF parser worked, but in his resume, the LinkedIn URL doesn’t have “https://” in front of it. So the system throws an error. That’s annoying. I can’t guarantee that people’s resumes have a “properly formatted” LinkedIn profile URL. So I either have to allow the system to accept the URL formatted without https:// or have the system format the URL automatically (which can lead to other issues). That’s a simple error / edge case issue in a relatively simple product. To build and launch a good product, you have to test everything and think through all the potential issues, including formatting, conditionals and more.

Complex Example: Behind the Scenes AI Functionality

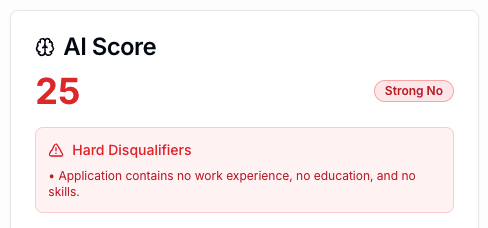

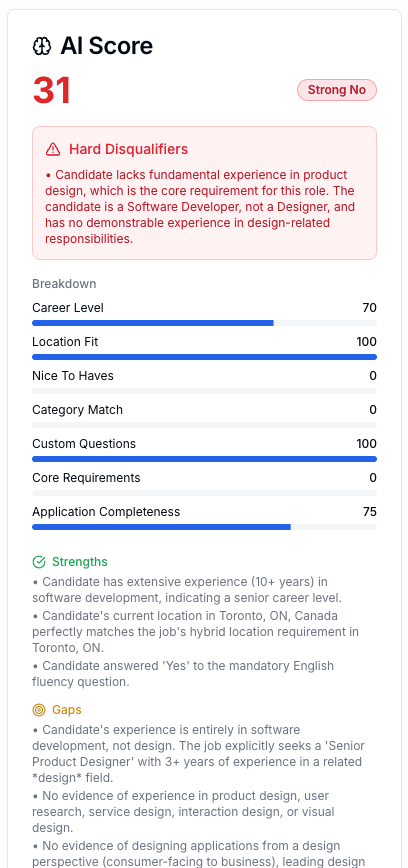

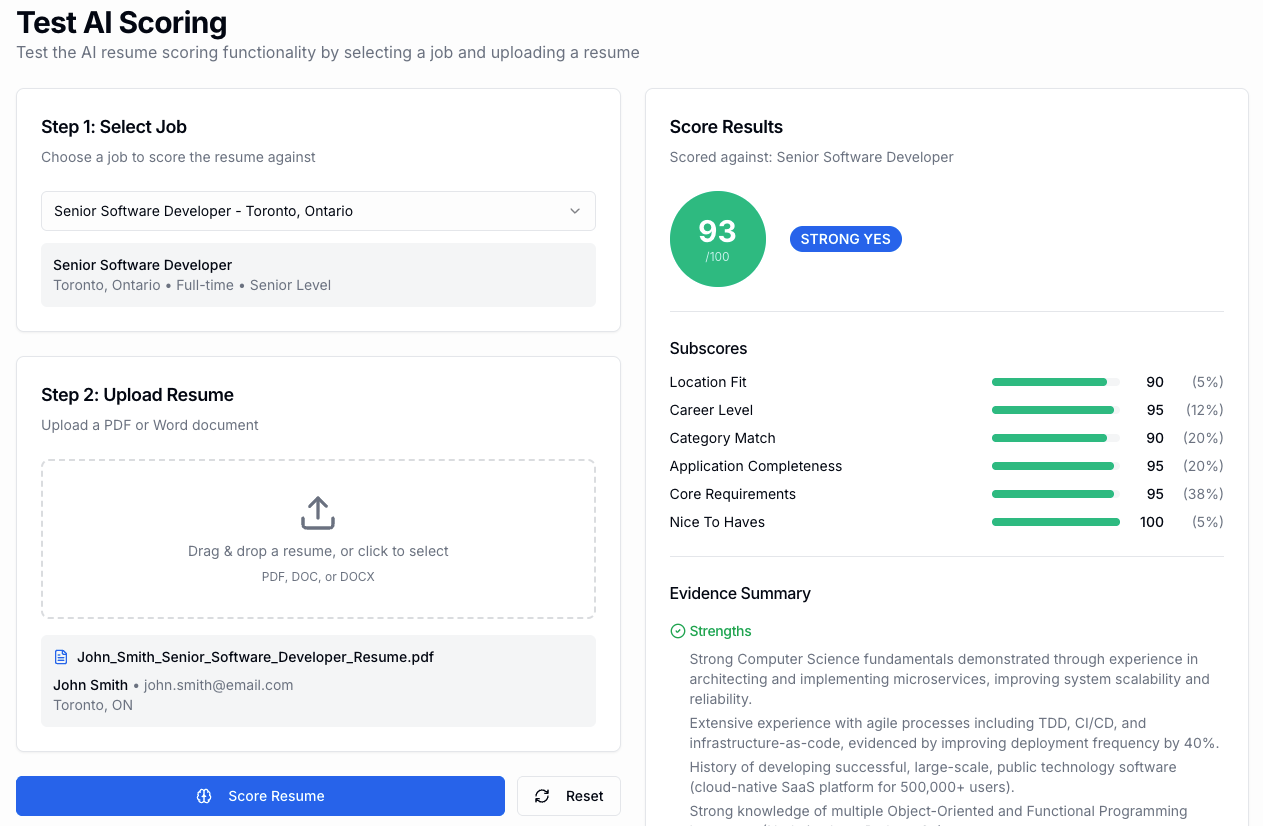

I decided to add an AI Resume Scoring feature to the ATS. Seems useful and our current ATS doesn’t have it. I worked with Lovable to build it and started testing resumes quickly. Instead of testing great resumes, I tested bad ones, because a big reason for AI scoring is to filter out applicants. Testing good resumes and getting good scores is the happy path—feels good, but isn’t thorough enough to know if AI Resume Scoring is doing its job.

Using two jobs (Senior Product Designer and Senior Software Developer) I started applying with very weak resumes. It would spit out scores, and then I’d have to decipher what the AI was doing. In one case it was scoring a near-empty resume (with junk inputs) higher than a better resume. Why? It turns out the AI was over-indexing on location. The junk resume was based in Toronto (same as the job), and the better, but still lousy, resume was in Vancouver. This took a lot of back and forth with Lovable to understand, as we worked to fine-tune the weighting.

Edge cases and errors often lead to new features

Testing the AI Resume Scoring with bad data (versus good data) led to two additional features: AI Scoring Explanations and Test AI Scoring.

When you think about edge cases and error handling (“What could go wrong?” versus “What could go right?”) it helps you realize what users of your software may need. The AI Resume Scoring tool was generating a score with no explanation. I knew my users wouldn’t trust it, so I built out the reasoning (which started lightweight and then got more detailed).

Here’s a partial screenshot of AI Scoring Explanations:

The Test AI Scoring feature is an admin capability that allows me to constantly test how AI scoring is working. To be honest, any time I make a meaningful change to the ATS, I should probably have a bunch of resumes and jobs setup to run the tests automatically. Right now it’s manual, which is super tedious and high-risk.

Edge cases aren’t just technical problems. They’re design problems:

What should happen when the system isn’t confident?

How much uncertainty is acceptable?

Who should see errors, and how?

When should the system stop vs keep going?

If you don’t make these decisions explicitly, AI will make them implicitly. And you may not like the defaults.

Progressive Building Is Where Bad Architecture Gets Exposed

Most real products aren’t built in one shot. They’re built progressively.

You start with something simple. A basic version of a feature. An MVP that solves the core problem in the most direct way possible.

Then you add to it: more capabilities, options, logic, users, rules, etc. This is normal. It’s how products actually evolve.

But progressive building through vibe coding has a sharp edge that people underestimate. If you haven’t thought through the underlying system design, each new layer increases the chance that something breaks, and not always in obvious ways.

The original version of the feature may still “work,” but:

new logic may not apply consistently to old flows

earlier assumptions may no longer hold

edge cases you handled before may resurface in new forms

tests that once passed may no longer mean anything

Adding new capabilities often feels trivial when you prompt AI to “Add X,” or “Support Y,” or “Handle this new case.”

But without a clear system model, those additions can bypass existing rules, conflict with earlier logic, introduce regressions you don’t immediately notice or create error states you never designed for.

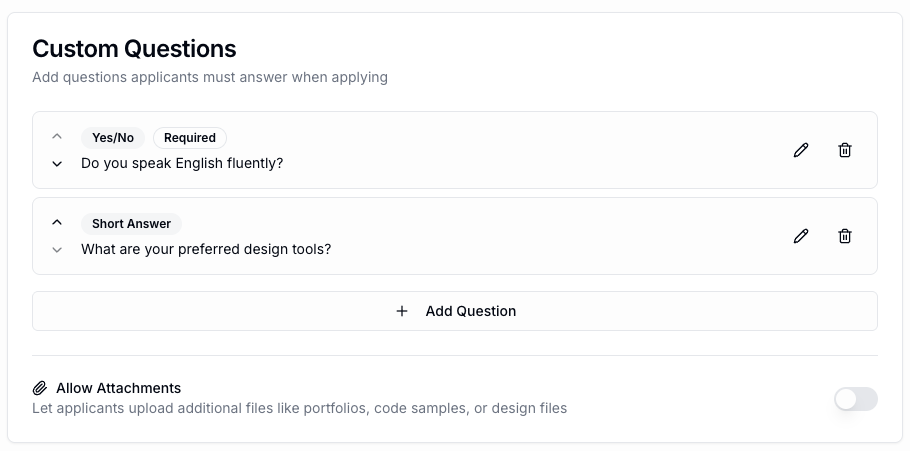

Example: Custom questions impact AI Resume Scoring

After setting up the basic ATS, I wanted to add a new application feature: custom questions. These are questions that can be created per job posting to ask applicants specific things. Lovable built a Custom Questions feature very easily, although I knew there were a couple issues to think about, including: What happens if the custom questions are changed or deleted after applicants have responded? (Note: Backwards data compatibility is always a huge issue). I decided on the appropriate rules for that and implemented the feature.

What I forgot to do was decide how these questions impact the AI Resume Scoring tool. If you’re spending the time to add custom questions to a job posting, they must be important, and you want the answers to impact scoring. But some of the questions may be yes/no, multiple choice or free form. Some questions are required and others are not. Do certain types of questions impact the scoring more? Are some question actually deal breakers? For example, if someone answers “no” to being able to speak English fluently, should that candidate be rejected automatically?

Oh boy.

Sometimes small features or iterations have a big impact. You can go down crazy rabbit holes and over complicate everything. AI coding tools will happily do that, because you’re asking them to (and it’s good for their credit-based business models!)

This all comes down to proper system design, thinking before doing, planning before vibe coding. You don’t want to over plan or overthink, but you should make some key design decisions before jumping in. Otherwise progressive building is a rat’s nest of crazy.

The Learning Curve Is Getting Steeper, Not Flatter

Here’s the challenge I find most interesting:

AI makes it easier than ever to start building.

It doesn’t necessarily make it easier to build well.

In fact, it does the opposite.

If everyone can build, everyone is making product decisions. If everyone is making product decisions without the core skills necessary, we’ll have a lot of bad products.

On top of that, when vibe coding, you actually need a broader set of skills, because product decisions are system decisions are code decisions. Vibe coding demands that you get things right earlier (if don’t want a total mess later) and shifts responsibility onto fewer people.

We need strong product judgment more than ever, and I’d argue stronger, more skilled product managers. Product managers should be builders (not just project managers), and now you’ve got a near-unlimited set of power tools to work with.

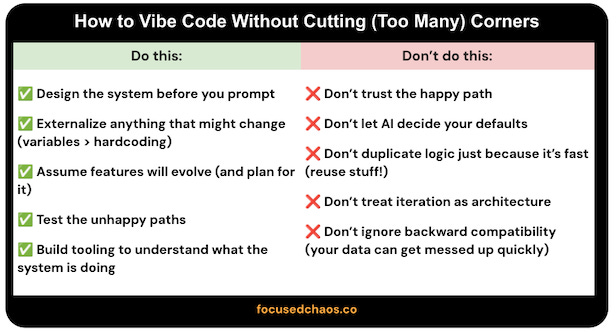

How to vibe code without cutting (too many) corners

✅ Do this:

Design the system before you prompt. Even a rough system sketch is better than letting AI invent your architecture.

Externalize anything that might change. If you think, “We’ll probably tweak this later,” don’t hardcode it.

Assume features will evolve. MVPs are the starting point, not the end state. Design with extension in mind.

Test the unhappy paths. Edge cases, bad inputs, ambiguity, and failure modes are where real products break.

Build tooling to understand what the system is doing. If you can’t explain why something happened, you don’t control it.

❌ Don’t do this:

Don’t trust the happy path. “It worked once” is not the same as “it works.”

Don’t let AI decide your defaults. AI fills gaps confidently, not correctly.

Don’t duplicate logic just because it’s fast. Repetition today becomes fragility tomorrow.

Don’t treat iteration as architecture. More prompts doesn’t equal better structure.

Don’t ignore backward compatibility. Breaking yesterday’s data is the fastest way to hate today’s feature

It’s amazing that AI empowers many more people to build products.

But the builders who succeed over time will be the ones who pair AI with basic and critical product management discipline.

AI is a power tool.

Power tools don’t eliminate craftsmanship. They punish the lack of it.

Solid piece. The 'accidental architecture' framing is spot on - I've seen this play out when prototypes suddenly become production apps and nobody realized they hardcoded environment-specific stuff everywhere. The test harness point particularly landed for me because last month I had to retrofiting testing into an AI-generated feature and it took way longer than building tests upfront wouldve. One thing I'd add: versioning gets messy too when the system doesn't account for schema changes from day one.

Thank you! This is excellent. I like the system sketch and 1 pager. We work now in 1 plan document which starts like a very stripped down PRD but just headers and bullets (what building, why, key use cases, features). Then we add into that the how and implementation plan including sometimes diagrams, mockups, data-models if needed. We build all this with Claude Code and iterate on it with Claude Code. Then we have Claude Code implement it, using this plan, and updating the plan as it goes. This has worked really well for us.