How to Design a Corporate Venture Studio

Get the free checklist to assess 60+ variables needed to design a corporate venture studio successfully. (#76)

Recently I spoke with two people that have a lot of experience in corporate venture studios: Brian Bemiller and Becky Splitt. Brian is an Innovation Engine Leader at 1848 Ventures. He was the first employee of the studio, started by Westfield Insurance. Becky used to work at Tenney 110 (American Family Insurance’s studio focused on proptech), but the studio shut down last year. They each share a very interesting perspective on the corporate venture studio model.

What is a corporate venture studio?

I define a corporate venture studio as a group or entity within a large company that builds & funds new businesses adjacent to the core company’s business. These businesses can be wholly owned by the big company and/or spun out into net new companies/startups.

It’s a model that’s increasingly popular as big companies explore how to innovate on the edges. It’s anything but easy. Countless attempts at growth or disruptive innovation have been attempted, including innovation labs, incubators, skunkworks projects and more. Many of these efforts fail.

Much of the challenge lies in the design.

There are a myriad of variables to address including structure, governance, recruiting/team, thematic areas and more. There’s no one-size-fits-all model for corporate venture studios. You can’t “buy a playbook”, implement it and assume you’ll win.

In this post, I go through the biggest variables and decisions you need to make if you’re building a corporate venture studio.

Introducing: The Corporate Venture Studio Checklist

I’ve put together a checklist specifically for corporate venture studios. It’s free to copy and use and will help you go through all the questions and variables you need to address while designing a corporate venture studio.

Why Build a Corporate Venture Studio?

The first thing you have to figure out is why you’re doing it.

I always ask people, “What does winning look like?” If you can’t answer that or there isn’t alignment with senior executives, don’t move forward.

There’s rarely one singular reason for building a corporate venture studio, but I’d encourage you to at least prioritize the reasons, so there’s little room for confusion.

Some common reasons:

1. Revenue Generation (Growth):

Your company has significant market share in its key areas, but growth has slowed (which is common as you get bigger). Leadership wants to diversify revenue growth opportunities and “look for the next billion dollar business.”

This is completely reasonable, but be careful about setting the bar too high, too quickly. New ventures take time to scale; most startups don’t even hit $10M in revenue over 3 years; and that’s a drop in the bucket for a big company. You should be able to help new ventures scale more quickly (b/c of your scale) but it’s not a guarantee. I’ve seen companies set targets such as $500M in new revenue within 3 years. Simply put, you won’t get there building new, tiny businesses.

2. Strengthen the Core (Differentiation):

Many big companies sell undifferentiated products/services. Think: insurance companies and banks. How does someone differentiate between life insurance policies? Or how radically different are banks’ mortgage product? In mature markets, products/services are often undifferentiated.

Building new ventures can strengthen the core through differentiation. Offer new products & services to existing customers to keep them from switching. Those same products & services may attract new customers before you sell them on your core offering. A great example of this is Ownr by RBC X (previously RBC Ventures, which Highline Beta worked with). Ownr allows people to register/create a new business. What do people need after that? A bank account. Business bank accounts are undifferentiated, but Ownr is different and it generates leads for RBC’s core business banking.

Brian Bemiller from 1848 Ventures shared this with me:

There are two long term outcomes we target: (1) direct financial value from the income generated from ventures that we launch; and, (2) the indirect financial value that we generate for our parent company, Westfield, via access to new customers and data.

Big companies can expand their offering through new ventures, each of which needs to stand on its own two feet as a legitimate business, but with the added benefit of driving leads & increasing overall customer value. Here’s a way of visualizing that:

3. Protect Against Disruption:

Big companies get disrupted. It doesn’t happen quickly, but it happens. Entire industries or verticals get disrupted by startups. Think: taxis versus Uber. Corporate venture studios can be a hedge against disruption because they’re meant to be building businesses “outside the core.” Those businesses could still help the core, but they should live separately, and tackle problems/opportunities outside of what’s already on a business’s or business unit’s roadmap. By the time you see the disruption coming, it’s probably too late. There’s a good argument to be made for using a corporate venture studio to validate (or invalidate) the disruption before it happens.

4. Navigate Around Legal, Compliance & Regulatory Challenges:

Big companies are often highly regulated, which can make it difficult to expand into new areas. A corporate venture studio (depending how it’s structured) can help. It provides a degree of freedom with respect to what is built and how it’s built.

5. Accelerate Learning:

It’s hard to put a value on learning, but corporate venture studios should be learning machines. They give you the opportunity to learn about new markets/user groups, existing markets/customer groups, industries/verticals, technologies, etc. These insights can feed a lot of the machine.

I’ve seen circumstances where companies were building venture studios to level up employees on new ways of working. Without question, studios operate differently from the core, but this can’t be the #1 reason to run a corporate venture studio. Training employees on being more entrepreneurial is a great by-product of a corporate venture studio, but shouldn’t be the focus.

6. Brand Building:

Although not a great #1 reason for building a corporate venture studio (b/c it’ll lead to a lot of innovation theatre), you shouldn’t ignore the brand impact. A corporate venture studio is a strong signal of an innovative strategy, which can bolster a company’s reputation with talent, customers, partners, investors, etc. You can choose to build a corporate studio quietly (behind the scenes), or be very public about it, and push forward a specific narrative.

Thematic Areas of Interest

Every corporate venture studio needs to define its key thematic areas.

RBC Ventures went “beyond banking” with the goal of building new businesses outside of core banking capabilities. That’s what led to businesses like Ownr and Houseful (which helps people find homes). 1848 Ventures focuses on the problems faced by SMBs running their businesses every day in retail, restaurants, hotels, real estate and construction. That’s led to businesses such as TakeUp (AI/ML to optimize hotel room rates) and Vandra (using real time visitor behavior data to generate dynamic discount offers). 1848 Ventures also has an AI-focused approach. Tenney 110 focused on proptech because of AmFam’s strong presence in home insurance.

Most corporate studios are vertical venture studios. This makes a ton of sense; a corporate studio should not go broad.

Along with the thematic areas of interest, corporate studios have to define two additional things:

What they won’t do (this is as important as what you will do; guardrails are important)

Closeness to the core

Closeness to the core is a key issue. You have to decide if new ventures will have a direct relationship (or not) with the core business. Often this is at the business unit level, where they’ve identified problems/opportunities to address but don’t have the bandwidth. Business units work closely with the venture studio to realize those opportunities and maintain close ties.

Alternatively, a corporate venture studio may work further away from the core and not rely on demonstrating short-term wins. Or the studio could do both.

In my experience the balance is helpful. If the corporate venture studio is too separated from the core business, someone will eventually question the ROI. If the studio has some early, small wins (i.e. helping a business unit with something on their mid-term strategy) it builds credibility within the organization.

Wholly-Owned Ventures or Spinouts

Corporate venture studios need to decide if they intend to own the businesses they create or spin them out as independent entities. The implications are significant to everything else in the studio’s design. For example:

Wholly-owned ventures can’t (easily) raise external capital, which means you need to fund new businesses exclusively. Spinouts typically raise external capital, but the ownership structure has to be investable (i.e. if you own most of the equity in a spinout, other investors will be less interested).

How you incentivize people changes radically. Wholly-owned ventures have no equity upside, but employees (who are employees of the big company) likely get higher salaries, better benefits and more stability than spinouts. I’ve seen different models including bonus structures, shadow equity and more. Spinouts come with equity upside, but less salaries/benefits. The risk (or at least perceived risk) is much higher on spinouts.

Talent acquisition changes significantly. If you’re spinning out startups you’ll attract more entrepreneurial people. If not, you may be relying on internal high-performers.

“Spinning in” (owning ventures outright) allows you to retain complete ownership, which has its advantages, but also disadvantages. Wholly-owned ventures need to operate under more rigorous “systems” including regulatory, compliance and legal, but also technical (security), infrastructure, hiring, etc. You have to decide if ownership warrants dealing with the internal challenges of innovation, or if you’re better off ceding (some) ownership to allow ventures to build on the outside and move at a faster speed.

You can do both spin-ins and spinouts, or provide optionality in the process for making the decision; i.e. get through some level of validation and then decide which way to go. But it’s complex because the approach can vary significantly between the two.

You can also build a model where you spin ventures out with a right to re-acquire them. This allows you to offset some of the risk, with a future option to control everything. The key is to design this in a way that isn’t too restrictive, limitingthe startup’s ability to execute independently. It is possible to balance these things.

Tenney 110 owned the ventures it built. Becky Splitt had great insight into this experience:

A corporate studio must be certain they bring an unfair advantage to the table. They have assets in the form of data, talent, capital, brand, technology, channels, and of course access to customers. These things can be nearly impossible for a startup from the outside to access. Indeed a wholly owned venture studio still has to jump through many hoops to unlock their potential. So whatever the unfair advantage is for a particular venture, that must outweigh the tax that comes with building a startup within a large corporation.

Corporate studios also, by and large, have a willingness to spend more funding and time up front to do the market and customer testing mentioned above before ever writing a line of code. Provided this doesn't dull an important sense of urgency or turn into bloat, that should lead to a better batting average over time.

Even at Tenney 110, where the studio was arm’s length from the mothership (a separate legal entity, intentionally prohibited from operating within the regulated insurance space, with capital to deploy), AmFam executives, who made up Tenney 110’s board, required that things like IT, security and hiring practices conformed with those of the corporation. Again, to compete with well-funded startups you must believe you can both leverage the corporation's assets and overcome the inertia of a large corporation with respect to each venture.

Validation Methodology & Team Structure

Like all venture studios, a corporate one has to figure out its validation methodology:

Where do ideas come from?

How are they initially vetted, for how long and by whom?

What are the key “stage gates” to go through from idea to launch (and beyond)?

Corporate venture studios and non-corporate studios follow a similar process. In my experience corporate studios take longer in validation, primarily because of the executive buy-in that’s required to move through the stages. Big companies are not used to endorsing and investing in “scrappy ideas,” which means they want to see “more meat on the bones.” Often this comes in the form of the business model and projecting a 5-year P&L. Market size is a big hang up for corporate studios because they’re already massive. I don’t believe market size should play as big a role, but I understand why it does. For a new venture to matter to a big company (that has a multi-billion dollar market cap) it has to scale.

Most venture studios “graduate” startups at an early stage (equivalent to the Seed round). The studios may continue to provide support, but those startups become portfolio companies and their success (or failure) is now dependent on the startup team. In a corporate studio, if you maintain ownership, you’re responsible for the venture forever, which means creating more stage gates and processes for defining validation. I often try to align this with financing rounds. Even if internally owned ventures don’t raise capital from external markets, it’s a good proxy. What does a startup need to get to Seed? Series A? Etc.? Although financing milestones aren’t simple or singular across all businesses/industries, they provide a decent benchmark for corporate venture studios. It also helps you understand what type of capital might be required to grow a new venture.

Two additional components that are affected by (and influence) the validation methodology:

The corporate venture studio team: You can model your studio similar to a non-corporate one, but chances are you’ll have the financial resources to hire a few more people (internally or externally as contractors).

When “founders” are recruited: You may recruit EIRs (Entrepreneurs in Residence) early on and work closely with them throughout the entire process (with the goal of them becoming venture leaders), or you might recruit EIRs/Venture Leads once something is validated (they become more “operators” of the new businesses).

Here’s how Brian Bemiller describes the process at 1848 Ventures:

While our process has many phases, there are two distinct parts of our organization. The first is the early stage venture creation “engine” that starts with market exploration in one of our core industries of focus (retail, restaurants, hotels, real estate and construction) and progresses through customer discovery and business model ideation and de-risking through hypothesis driven, in-market testing. Throughout these phases, many alternative problem spaces and business model ideas are explored and tested. Many of these are ultimately shut down or significantly pivoted.

For those that progress through the aforementioned hypothesis driven, in-market testing, the venture is transitioned to an experienced B2B SaaS leader to carry the momentum forward into early customer acquisition, product launch/go to market, and the original team heads back to the beginning to restart in a new space.

For those ventures that experience early indicators of future success (initial customer acquisition, customer feedback, market understanding, etc.), a Seed investment is provided to drive additional customer growth and progression on the journey towards product market fit and scale. Once that investment is made, funds are leveraged to build a team around that specific venture and execute a Seed investment plan, iterating along the way informed by learnings from customers and the market.

Here’s how Becky Splitt describes the process at Tenney 110:

The ideation and validation process at Tenney 110 evolved over time, though always started with a deep understanding of a customer pain point, in an adjacent space believed to be strategic to the company. Subject matter experts were brought in to spend a week with a small core team of design thinking, market research and insurance business experts. After generating, prioritizing, and winnowing out good ideas for potential ventures using well defined criteria, a few concepts were selected to move into validation.

The validation process varied based on complexity and access to potential customers, lasting between 4-12 weeks. This was a rigorous process of customer and market testing, as well as scoping the solution and a plan to operationalize it, in order to test viability. It almost always involved iterating on a concept mock-up (often a website) or light prototype, and interviewing a pipeline of prospects.

A typical validation team consisted of a few folks who participated in the sprint week, as well as a member of the studio's product/tech team. If no available Entrepreneur-in-Residence (EIR) was a good fit to lead the team, one of these individuals would serve as the venture lead through validation. Other resources from the studio and enterprise were leveraged as needed for things like financial modelling and refinement of market sizing. Importantly, a senior leader from within AmFam was identified as a sponsor. The inability for a senior executive to get excited about the concept was a sure sign of poor fit for the studio, even if it otherwise demonstrated high potential.

There are similarities and differences between the two. In my experience there’s no cookie-cutter way of doing this; it has to be designed based on the circumstances of the corporate and the studio they’re aiming to create.

Finding the Right Talent for the Venture Studio

Building the right corporate venture studio team is critical. These individuals (i.e. researchers, designers, developers, product strategists, etc.) do not need to be entrepreneurs or crazy risk-takers, but they do need to be entrepreneurially-minded.

The pace will be faster with less red tape than within the corporate structure. The team has to thrive in that environment.

The team has to love experimentation & learning, recognizing that 0 to 1 is radically different from keeping the big company moving. Within the studio it’ll feel more chaotic and things will change daily (if not hourly). Affecting the big company is like moving an oil tanker.

Failure becomes a significant part of the process in a venture studio; the team has to be prepared and comfortable with that. Team members can’t feel like their performance reviews, bonuses or status within the company will decrease if they invalidate things.

High performers from within the core company are not always suited to working within a corporate venture studio. They may see it as an opportunity to level up within the organization (pursuing the latest “shiny object” to raise their profile). While I completely appreciate career pathing within a large company (and the opportunities that provides), don’t hire people into the corporate studio that are fixated on that approach.

The roles with a corporate venture studio are specialized to the type of work being done. A user researcher or designer from the big company may not be the right fit. For example, a user researcher in a corporate studio should spend a lot of time doing scrappy user interviews with a dozen people as opposed to extensive, statistically significant surveys. A product designer in a corporate studio will spend a lot of time doing rapid prototyping versus pixel perfect marketing campaigns.

In my experience the best thing you can do is find a balance between internal and external people. The internal resources know how the company works and have a valuable internal network. The external resources come with a “burn the ships” mentality, which can breathe life into how the studio operates (although it can also create tension!)

EIRs are most likely recruited from the outside, especially if the intention is to spinout new companies. Every organization has entrepreneurial-minded individuals that can play a big role (“intrapreneurs”), but if you’re looking for startup experience (i.e. repeat founders) then you’ll need to look externally. Recruiting EIRs is a big task—you have to convince people (ideally past founders) that taking a role at your corporate studio will be rewarding and meaningful. If there’s no chance of spinning out, it’ll be a harder sell, but not impossible. I know quite a few people that want to build new ventures from 0 to 1 without the same level of risk they’d have doing it on their own.

Governance & Budgeting

A corporate venture studio needs a unique governance model compared to the core.

Most commonly a venture board is created with internal stakeholders, including key senior executives and the people running the studio. On occasion, external people are invited to sit on the venture board as well, to provide a different perspective. This is a smart move. External venture board members look at each venture with an objective lens, largely free of any politics or stakeholder management that’s taking place. External venture board members often wear the “investor hat” measuring ventures based on whether they’d invest or not (even if they’re not able to because the ventures are wholly-owned).

The venture board needs to understand and align with the stage gates being used to validate ventures. These stage gates look very different from how they approve and fund core projects. It takes some practice, and it’s easy to fall back on what you know from the core to measure new ventures. But the yardsticks are different.

I often ask venture board participants, “Would you invest your own money in this idea / opportunity / business?” It creates a different perspective on how to look at things. I also think it’s helpful for venture board members to spend time with investors (particularly pre-seed and seed stage) to understand how they look at things, judge businesses and make decisions. Early stage investing is done with a small amount of data and validation. Most decisions within a big, mature business are made with lots of data.

Budgeting in a corporate venture studio is very different from within the core business. Big companies budget annually, and there’s often a “use it or lose it” approach. The bigger the budget, the more power. In a venture studio (like a startup) it’s very difficult to predict what you’ll need in 12 months. You want ventures to be small and nimble, not bloated with people and process. But people and process equals more money, and I’ve seen studios over-budget in order to guarantee dollars are allocated. Once they over-budget they almost always overspend.

In an ideal world, capital would get unlocked at each stage gate of the venture. The venture team, led by an EIR, pitches the venture board. The pitch should look more like a startup pitch than a typical corporate presentation. There’d be an expected dollar range ask per venture (just like there would be in external financing rounds). The money is allocated to get to the next major milestone, which needs to be agreed upon before moving forward.

The core venture studio has a budget as well, most of which is spent on people executing the early validation work and supporting the ventures as they mature through the studio model. This doesn’t have to be a big team. Winning in a corporate venture studio isn’t about securing the biggest budget and hiring the biggest team. That approach almost inevitably leads to the venture studio shutting down because it simply cannot generate enough value for the cost.

How To Measure Success

Measuring success in a corporate venture studio is different from the core business. In the core business you’re measuring revenue and profit, market share expansion, and other metrics suitable to a mature business. In a venture studio there is no revenue, profit or market share (at least early on). It can take years for a startup to hit $1M ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue), which is a significant milestone. In the context of a billion dollar business, you might as well round down to zero.

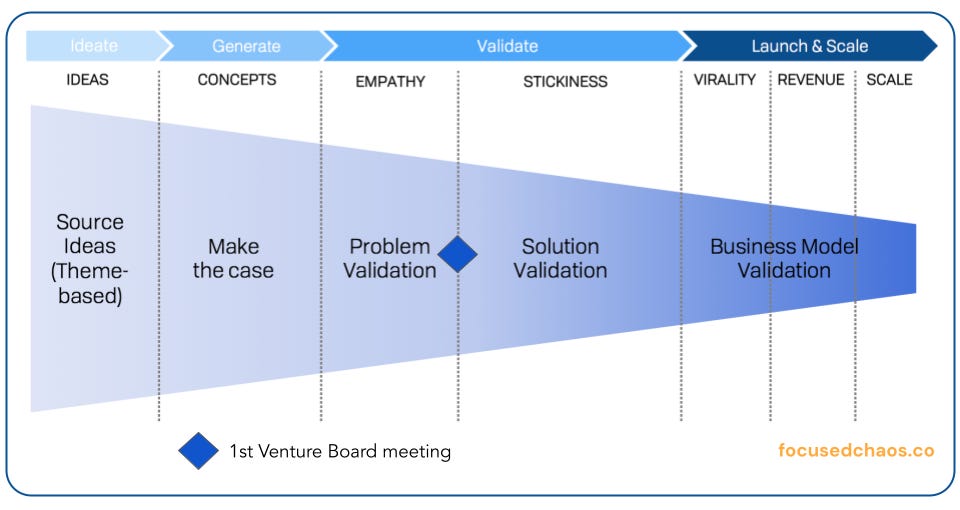

Metrics in a corporate venture studio are more inline with startup metrics, and I use Lean Analytics to help. Here’s a good case study on how to use Lean Analytics. And here’s a way of visualizing early businesses.

Corporate venture studios live in Empathy and Stickiness. They’ll get into Virality and Revenue, but rarely Scale, because at that point you’ll have done something with the venture; either spun it out or spun it in as a new line of business (or as part of an existing one).

Measure the success of individual ventures: First you want to establish the right metrics for each individual venture. Stickiness, for example, varies depending on the type of business. If you’re building similar ventures each time (i.e. only B2B ventures for SMBs) then you can develop a good framework for consistent metrics across the portfolio.

Measure the value back to the core business: Next you can try to assess the value attributed back to the core business. This will vary depending on how your studio is designed. If it’s connected and driving leads back, you can measure the value of leads. If it’s completely independent, the value back to the core is tougher to assess. You can look at brand building, talent recruitment, retention and skill development. Learning is also worth measuring—how much have you learned and what decisions have been made as a result? A corporate venture studio should connect into your M&A team (for making acquisitions), your CVC team (for making investments) and other business units, feeding them user/customer research, new insights, etc. Recognize that any material value in the form of leads, customers or revenue takes years.

Measure the value of the portfolio: Finally, you can look at the value of the portfolio. This is tough to do unless you’re spinning companies out (in which case they’ll have a value assigned to them by external investors). One option (even if you’re not spinning ventures out) is to use an external investor viewpoint. Although there’s quite a bit of variability in what companies are valued at different stages, there are reasonable ranges. For example, a Seed stage company probably has a product in-market with early traction and has raised $1-$5M with a value of $5-$20M. You could split the difference and use averages to get an overall portfolio value. As your portfolio matures you could use a multiple on revenue or something similar.

Initially, focus on getting really good at measuring individual venture progress. This is where most venture studios fail because they’re using unspecific or unrealistic measurements & benchmarks.

Conclusion

To build a successful corporate venture studio requires patience. You won’t see $100M in revenue overnight. You won’t launch 10 successful ventures in the first few months. There has to be a top-down willingness to take the right approach. Having said that, a venture studio doesn’t require a huge budget. It can be done with a small team, the right process and enough air cover to take a shot.

You also need to be willing to iterate on the “operating model” because things change. You may realize that the validation steps are wrong, or the funding approach needs tweaking. I can almost guarantee you’ll churn talent because people won’t fit into the new ways of working. Very little in a corporate venture studio is set in stone, because the whole exercise is an experiment. You set your goals (whatever they may be) and build the best possible “system” to achieve them. Then you try, iterate and learn. Over and over again. Corporate venture studios are so different from how core businesses operate that you have to take an experimental approach. Mistakes will be made. But it’s through that process that you have a chance of building net new ventures that can have a material impact on your business.

If you’re looking to build a corporate venture studio (or improve one), please reach out! I’m always happy to share my experience and provide feedback.

💪 You can also access (and copy) for free, the Corporate Venture Studio Checklist. It covers 60+ variables to consider when building a corporate venture studio.

📚 I’ve written extensively about venture studios. Read it all here.

Whoa! great timing! Thank you!

Great read