Differentiation and Specialization Done Right

Being different isn't enough. You need to differentiate on something that matters to customers. (#81)

Being different for different’s sake is tough. Roadside attractions pull it off, but they must have close to 100% churn. How many times can you visit the “biggest whatever…” or a museum of hammers? (Yup, there’s a Hammer Museum in Alaska.)

Founders know they need a differentiator, but often they can’t figure it out. In these situations, they usually fall back on two options:

Team: “Our team is second to none, we’re the greatest team ever.” That’s cool, although probably not true. On top of that, customers don’t care. Investors might be impressed, but they see a lot of great teams.

Speed: “We execute faster than anyone else. We have the fastest team.” Speed matters, but it’s not enough to truly stand out.

Both of these are important, but in a world that barrages users and customers with new things, 24x7, you need more precise ways to differentiate.

Liquid Death pulled this off by initially marketing towards straight edge adherents and fans of heavy metal music and punk rock.1

According to Wikipedia, founder Mike Cessario was inspired to create the brand after watching a Vans Warped Tour in 2009 where concertgoers drank water out of energy drink cans. He thought marketing water the same way would work. Before launching, he produced a video ad to gauge market interest, which received 3M views.

The brand hit mainstream (February 2020) when it expanded into Whole Foods and according to Eater became “the fastest-selling water brand on its shelves.”

Liquid Death started with a very specific target audience, one that other food & beverage brands ignored. But clearly there was an unmet need and an occasion where people were looking for a solution.

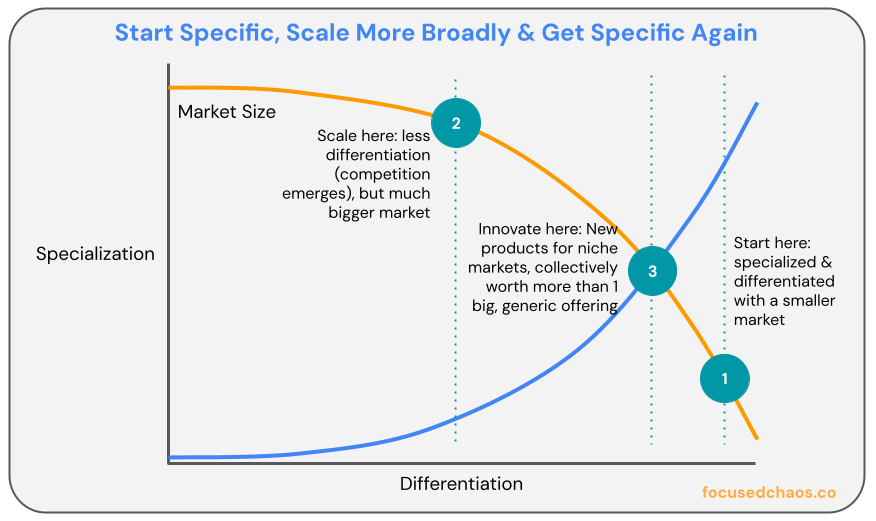

As you specialize, differentiation naturally goes up.

The more specific you are about a target user/customer, the more differentiated you’ll be against competitors (who target broader audiences).

The more specific you are about a solution (“our product is the best at A, and we don’t do B, C or D”), the more differentiated you’ll be against competitors (who provide a wider set of capabilities, likely in a shallower way).

The challenge is that market size goes down with increased specialization.

The more you specialize—increasing differentiation (which is a good thing!)—the more you shrink the market (which is dangerous).

If market size is too small, you may struggle to:

Identify and reach customers in a repeatable way

Raise capital (investors generally prefer “big markets” although I disagree)

Scale

The key is to figure out the right degree of specialization that allows you to positively differentiate in a big enough market.

“Right degree of specialization” = you’re targeting a narrow enough user/customer group such that they know you’re speaking directly to them; or, in product terms, you’re 10x+ better than competition in a very specific way/feature set because of the capabilities you offer.

“Positively differentiate” = you’ve differentiated in a way that your users/customers actually care about. If they don’t care, your differentiation can hurt you.

“Big enough market” = there’s enough reachable, similar users/customers that you can prove product-market fit (going beyond early adopters) and scale. You have to hit product-market fit in the smallish market you pick. Otherwise you’ll need to pivot (which is fine, but different than moving successfully between markets).

➡️ Wanna chat? Find me on Intro!

Book time with me here: https://intro.co/BenjaminYoskovitz

If you’re interested in my help with your startup, venture, project, etc. please get in touch. I’m happy to help as best I can on topics such as:

Building products

Fundraising / pitching

Startups in general

Venture studios

Etc.

50% of proceeds go to Ronald McDonald House (for which I have a very personal connection). 🙏

VarageSale Differentiates on Community, But Can’t Achieve Escape Velocity

Between 2014 and 2016 I was VP Product at VarageSale, a buy & sell marketplace. Before joining the company I was one of its first angel investors. VarageSale differentiated from competitors in two ways:

The communities were closed (you had to be approved) and hyper-local. Competitors allowed you to search by distance, but they weren’t as community or locally focused as VarageSale.

The brand was focused on women. This meant that certain item categories outpaced others (i.e. baby clothing/items were huge). Men were allowed in, but I’d estimate that 80-90% of members were women.

Both of these differentiators drove everything we did in terms of product, marketing, customer success, etc. They were a big reason for our initial success. VarageSale was the place to go for women that wanted a safer, hyper-local, community-focused experience.

But our differentiators were also our downfall.

Closed, hyper-local communities don’t scale, at least not super quickly. We had to keep building new communities from scratch, which was difficult. They didn’t have the same vibe as our older communities, and grew more slowly.

Eventually it was decided that we’d allow items to automatically cross between communities, even if they weren’t intentionally cross-posted. The goal was to encourage more engagement and transactions, which in turn would drive user growth. It was a huge project that required rebuilding much of our back-end systems (which were always designed for 1 item in 1 community). We tried easing people into the experience, but many were unhappy. They didn’t want to travel too far to transact, or they were suspicious about people they weren’t community members with.

What made VarageSale special — it’s tight-knit community feel — stopped it from scaling exponentially, which became a deal-breaker after we raised $30M+ from U.S.-based VCs.

While we were trying to figure out how to maintain awesome communities and scale, competitors took different approach. Many of them focused on making buying and selling as easy as possible, with less community or geographic constraints. They focused on bigger items (i.e. cars, electronics, etc.), which are predominantly bought and sold by men. They raised huge sums of capital and were able to drown everyone else out. It doesn’t mean they built financially successful businesses (many struggled with their revenue models and profitability) but they took a different approach—specialized, but less so, which meant a bigger market.

As this was happening, we were debating whether to differentiate VarageSale even more. The idea was to focus exclusively on women. To be clear, we didn’t have any major issues with men on the platform, but we thought that a buy & sell platform exclusively for women would further differentiate us in a way that might scale (while we continued to decrease the focus on closed community). We thought there’d be a lot of PR and media attention and we could lean even further into our focus on safety (which came naturally to us as part of our focus on women).

The hypothesis was this:

We had to lower the focus on close-knit communities to allow more members into VarageSale, and allow more items to be seen by more potential buyers. A lot of existing VarageSale users didn’t like this, but new users wouldn’t view it as negatively.

Going “women only” would counter-balance point 1, by further differentiating us against competitors and increasing the sense of community (even when geographic boundaries were being dissolved).

We never did it. We didn’t have the guts to take the decision and there was concern that we’d shrink the market too much. I wish we had tried. It would have been a bold move in a growing sea of sameness.

Differentiating on Tech Alone is Tough

A lot of startups build a solution and then search for a problem. It’s not impossible, but it’s incredibly tough to do.

When I joined GoInstant in October 2011 that’s exactly where we were. The company had built incredible technology to enable co-browsing without any plugins. The tech was wild. The problem was that we weren’t sure who would use it and why.

We had hypotheses. For example, we were confident that salespeople would love the technology because they could easily do real-time interactive product demos. Online meeting tools at the time only allowed you to share your screen or share control back and forth in a clunky way. GoInstant allowed two or more people (with two or more cursors) to interact seamlessly. Getting someone to actively engage during a sales demo is powerful. We also thought customer service was a natural fit. If someone was having an issue with your software, you’d jump into GoInstant and navigate through it with them collaboratively.

We had a few consumer ideas too, like booking travel with a partner, or co-shopping. But none of this was validated while the tech was being built.

In GoInstant’s case we had specialized and differentiated on technology but not on use case. This made it tough to figure out what product to build around the core technology. It also made it difficult to make tradeoff decisions because we were trying to keep the use cases broad.

Reflecting now, we should have more quickly identified one killer use case and gone all-in. The underlying technology wouldn’t have changed (which means we could have moved from one use case to another), but the product wrapper and GTM strategy would have been very clear. We could have aimed to be the “world’s greatest [fill in the blank] solution” as opposed to “a super cool co-browsing technology for whatever you want to do.”

Lesson learned: People understand use cases + occasions

Make it dead simple for users / customers to answer these two questions:

How should I use your solution?

When should I use your solution?

The combination is what helps create new behaviours and drive product stickiness.

If I know how to use your solution, but I’m not sure when, I may forget or go back to whatever I was doing before.

If I know when to use your solution, but not how, I’ll get frustrated and give up.

OpenAI was founded in 2015, but it wasn’t until ChatGPT launched that people got it. And while ChatGPT can be used for a lot of things, they put a lot of effort into sharing example use cases; even including prompts in the UI to suggest what it’s capable of.

Start Narrow & Expand

Generally, I recommend starting with the smallest possible niche and expanding from there. This allows you to hone in on specific use cases and occasions.

Facebook started with college campuses and eventually expanded to the general population. These days, it’s more popular with an older demographic and has lost its original target user (young kids / college students move on to Snapchat, TikTok, etc.) Part of Facebook’s go-to-market approach was to create exclusivity and hype. Pete Flint does a good job talking about different wedges for growth.

Uber started with black cars for business travellers to compete with taxis, before bringing their service to a wider population. Interestingly, Uber went from niche to general population (UberX) and back to niche, by launching different types of vehicles (including Green, UberXL, Uber Pet and Share). This is a common pattern for companies at scale—they start in a specific vertical, expand significantly, and then re-specialize into additional key verticals (often through acquisition).

If you scale massively, naturally you’re delivering a broader, more generic solution. It also means there’s going to be increased competition from other big players and niche upstarts. New innovation happens at the right intersection of a specialized (and therefore differentiated) value proposition, with a reasonably large market size to make an impact (especially if you’re already a big company). Big companies can leverage their user base, brand, experience, capital and sheer muscle to build new solutions in niche, adjacent markets, which collectively defend the companies’ borders and increase the overall value they deliver.

Starting narrow allows you to stand for something.

Be distinct. Build a great product for a specific user / customer group and nail your use case + occasion. Generate publicity and buzz. Grow a following. Create a movement. Win by being different, before winning by being the same, or more similar (only to veer back towards aggressive differentiation again).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquid_Death

> “Our team is second to none, we’re the greatest team ever.” That’s cool, although probably not true.

I know I can always count on you to be real af, Ben

This article will help a startup of a friend. Just two hours ago we talked about this topic. Thanks Ben!